The living sea cows of the order Sirenia, three recognized species of manatees (Trichechus) and one species of dugong (Dugong), are the last survivors of an extraordinary and diverse group of marine mammals. All sirenians, past and present, have been grazing mammals, thus the epithet ‘sea cow.’ Freshwater species browse(d) on the aquatic plants found in rivers, estuaries, and lakes, while marine species graze(d) on seagrasses or kelp. Some of the earliest sirenians may have lived both on land and in water, and their eating habits over time ranged from eating a wide variety of plants to being more selective (Domning 2001b).

Within the creation model, sea cows offer an interesting take on biogeographical expansion after the Flood. After all, being aquatic, though air-breathers, sea cows were outside the Ark and survived the turbulent Flood. This means there was never a point where only one pair of this group survived the Flood, which would have drastically limited their genetic diversity. This means that the immediate post-Flood sirenians could potentially have included multiple genera or even families within a single created kind. After all, the original created sea cows had a significant amount of time to multiply and differentiate as they ‘filled the earth.’

The First Sea Cows

One evolutionary biologist has noted (Domning 2001b), “Although sirenians are thought to have arisen in the Old World . . . they seem to have spread quickly to the New World end of the Tethys Seaway, where their actual fossil record begins in the late Early Eocene of Jamaica,” but it wasn’t long before Eocene fossils in the Old World were discovered. Evolutionists attempt to tie sirenians in with elephants and kin (the proboscids) and a few other fossil groups in the clade Tethytheria, but there are no specific ‘ancestral’ fossils confirming such a common relationship. That’s just evolutionary speculation. As Heritage and Seiffert (2022) noted, “a temporal comparison of the earliest known sirenian fossils to the supposed age of the Sirenia-Proboscidea lineage split . . . suggests that the first 10 million years (or so) of the order’s evolutionary history has not yet been documented by fossils. Conversely, the middle Eocene to Recent fossil record of sea cows is quite good . . .”

Creationists can note that fossil sirenians first appear in the Eocene period, likely after the Flood, and that sirenians probably aren’t found in rocks formed during the Flood itself. This may simply be due to how the Flood occurred: some ecosystems (like those with significant human populations) were likely wiped out without a trace.

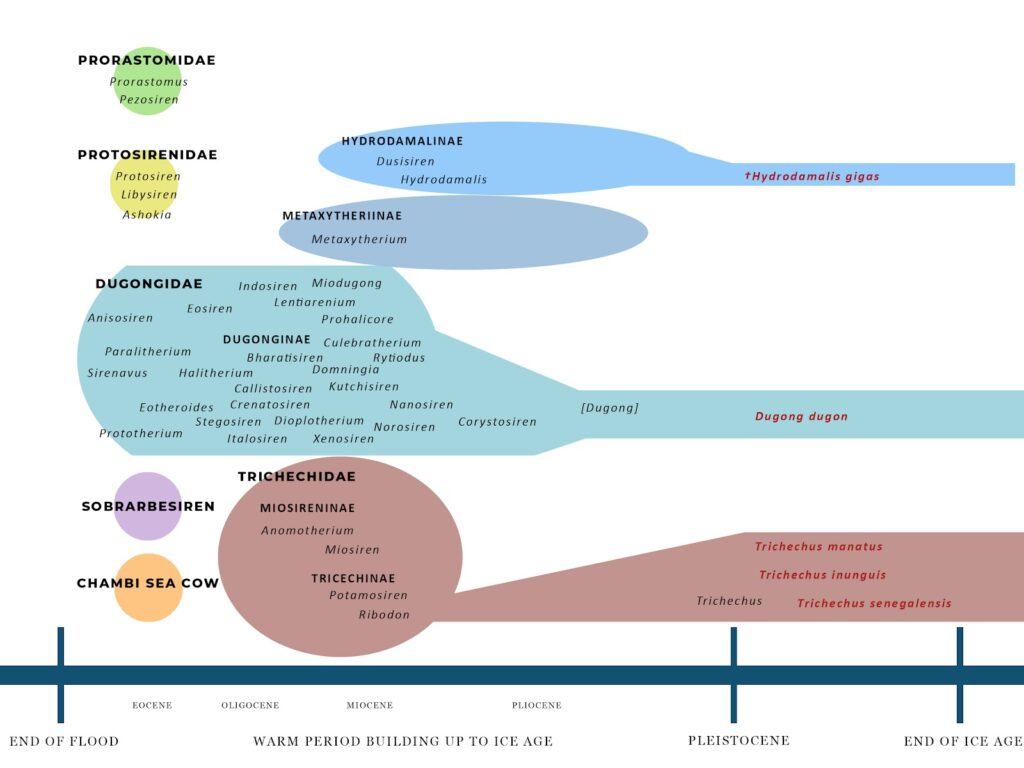

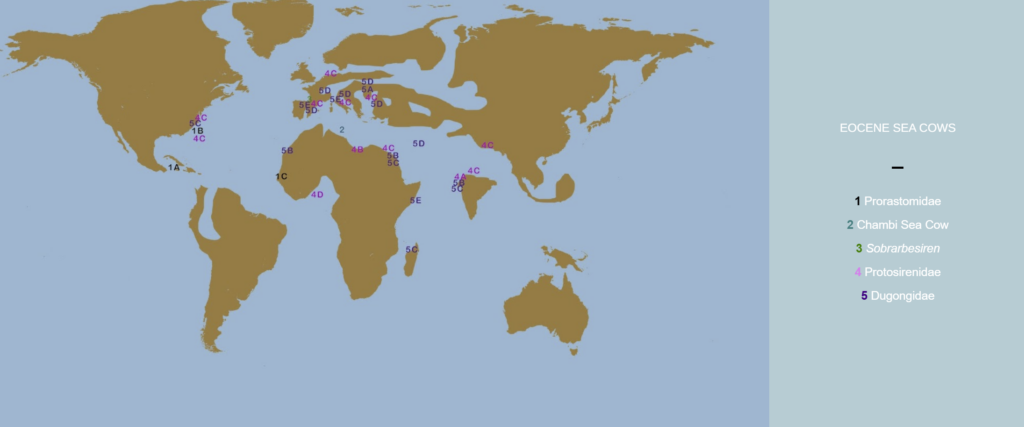

But unlike the evolutionary perspective, who look at the Eocene as an epoch straddling over 20 million years, for a creationist the Eocene is very near the start of the post-Flood period. (How near, still requires discussion, particularly as it may not be consistent across all continents.) But during the Eocene, at least 13 different genera of sirenians make their appearance. Those are in three of the four recognized families of the order Sirenia: the Prorastomidae, the Protosirenidae, and the Dugongidae. An additional eight genera show up in Oligocene deposits, though seven are in the Dugongidae and one is the first of the family Trichechidae (manatees). What does this suggest?

Early Sea Cow Diversity

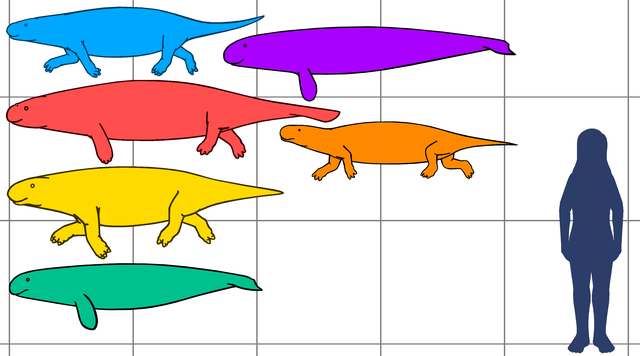

The first thing it suggests is that sirenians were a highly diverse group prior to the Flood. Were all sirenians part of a single created kind? That’s not as clear. A number of ‘popular’ creationists seem to have difficulty with the idea of large vertebrates showing limb variation. (Yet they don’t seem to object to amphibian or reptile created kinds showing that degree of variation.) Unlike modern sirenians, which only have front flippers, some fossil sirenians had four legs and may have lived both in water and on land. So, it’s possible that each of the four families of sirenians were distinct and represented separately created kinds. They might also represent 2,000 years of pre-Flood diversification and physical changes within a few created kinds—or even just one created kind.

It should also be noted that these Eocene sirenians are not showing up in the very same area. These fossils likely show where small groups of sirenians managed to disperse after surviving the turbulence of the Flood.

After this initial Eocene period, two families that survived the Flood soon disappear, while the family Dugongidae begins to diversify. Not every pre-Flood organism survived long in the post-Flood environment. Climate and habitats continued to change, as they hadn’t yet stabilized. Sea cow distribution was dependent on healthy seagrasses and other aquatic plants. The dugongids took advantage of waning competition to move into new habitats, and were able to adapt to different feeding niches in the post-Flood world.

Eocene

Three families of sirenians appeared in the Eocene: Prorastomidae, Protosirenidae, and Dugongidae. There were also a few genera whose family isn’t certain, like Sobrarbesiren, which seems closely related to the Dugongidae (Díaz-Berenguer et al. 2018). Most species were smaller than today’s West Indian manatee, about the size of a pig (Suarez et al. 2021).

Each of these groups had different limb structures and ways of getting around. Prorastomids, Protosirenids, and Sobrarbesiren all had four legs, but they differed in how they swam and moved. Dugongids, on the other hand, were fully aquatic and had no hindlimbs (Díaz-Berenguer et al. 2020). This variety could suggest they were separate created kinds, or it might show that there was a lot of pre-Flood diversification within fewer kinds. This diversity would have allowed different sirenians to live in various ecological roles in the same area.

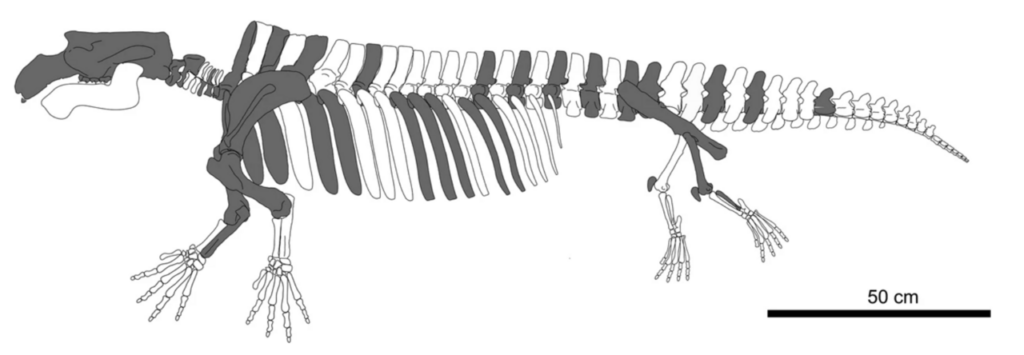

Prorastomidae: The Prorastomidae included two genera: Prorastomus and Pezosiren. These animals had four legs and likely lived like hippos, preferring shallow aquatic habitats with lots of vegetation to eat (Domning 2001a; Savage, Domning, and Thewissen 1994). These were coastal and estuarine habitats (Benoit et al. 2013). Pezosiren, the best-known member of this group, had features for both land and water. Its skeleton could support its weight on land, but it also had traits for aquatic life, like heavy, dense ribs, retracted nostrils, and no paranasal air sinuses (Hautier et al. 2012; Díaz-Berenguer et al. 2020). Prorastomids had narrow, forceps-like jaws that seem suited for selectively eating plants, both from the surface and underwater (Domning, Hill, and Sorbi 2017).

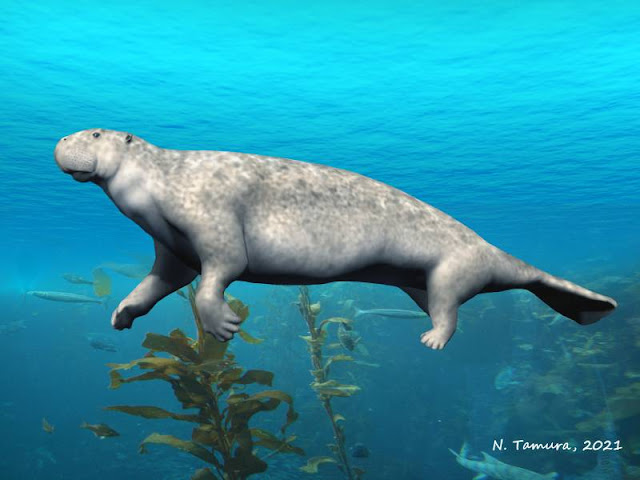

Protosirenidae: Protosirenids (or at least Protosiren) had four legs, with small but functional hind limbs. If they moved on land, it was probably like a seal or walrus (Díaz-Berenguer et al. 2020). Protosirenids were adapted “toward grazing on meadows of bottom-growing seagrasses: the cropping apparatus is broadened,” while incisors and canines play little role and may be significantly reduced in size (Domning, Hill, and Sorbi 2017). Protosiren had large tusks, no dense rib bones, and unique rib connections that may have helped with breathing and buoyancy (Zalmout and Gingerich 2012). These features suggest it could feed on seagrass roots in deeper water, and its hind limbs may have helped it move along the seabed.

Dugongidae: Eocene dugongids were already fully aquatic animals with no external hind limbs and swam using their tails. They only had small, vestigial pelvic bones and femurs (Díaz-Berenguer et al. 2020). Dugongids like Eosiren and Eotheroides had closer-packed ribs than other Eocene sirenians and may have inhabited shallower water “where it was easier to come to the surface to breath” (Zalmout and Gingerich 2012). Zalmout and Gingerich (2012) also noted, “Sea grass preserved as leaf impressions is direct evidence of the shallowness of Tethyan shelf waters where Eocene sirenians are found in Wadi Al Hitan and elsewhere.”

Sobrarbesiren was a larger Eocene sirenian, about 2.7 meters long (Díaz-Berenguer et al. 2018). Although it had four limbs, it probably could not walk on land because its limb bones were likely brittle and not suited for moving about on land (Díaz-Berenguer et al. 2020). Díaz-Berenguer et al. (2018) suggested this represented an evolutionary stage between fully mobile four-legged walkers and swimming sirenians lacking hind limbs. However, all these ‘stages’ appear at approximately the same time after the Flood. Now, dugongids did reduce their limbs from practically vestigial to fully gone, so limb reduction is certainly possible. Díaz-Berenguer et al. (2018) also suggested that Sobrarbesiren could potentially be ancestral to the Trichechidae, but the latter may also be an early offshoot of early dugongids.

The Chambi Sea Cow: The available fossil material didn’t allow for placement in a recognized family, but evolutionists believe that this is the oldest fossil sirenian, found in a freshwater deposit in Tunisia (Benoit et al. 2013). It had a number of ‘primitive’ sirenian traits, but demonstrated morphologically that it was well-adapted for an aquatic lifestyle. For example, it could likely hear underwater.

Oligocene

By the Oligocene, the Prorastomidae and Protosirenidae have disappeared. Only the Dugongidae continue to be found in Oligocene deposits, but two different subfamilies begin to differentiate from within the numerous dugong genera (Domning 1997): the Dugonginae and the Metaxytheriinae. (There are a number of ‘primitive’ dugongs that continue to show up in the Oligocene, but most of those disappear by the Miocene.) Another sirenian also shows up, Anomotherium, the first true trichechid. An offshoot of Sobrarbesiren’s lineage? In any case, it is part of the subfamily Miosireninae which differs substantially from the modern manatee’s lineage. Additional fossil material will likely be necessary to understand manatee development during this time.

Miocene

Dugongidae: During the Miocene, the more ‘primitive’ dugongs were starting to disappear, while the distinctive subfamily Dugonginae experienced a lot of growth and variety. This period was, in fact, when dugongs were most diverse. They were also spreading outside the former Tethys Seaway, into both sides of the Pacific. Vélez-Juarbe et al. (2012) noted that Dioplotherium and Metaxytherium ,found in Miocene Argentina, probably spread along the coastline, following seagrasses into the inland Paranense Sea. Bianucci et al. (2006) noted that a dugong tooth was found in the Upper Miocene sediments of Chile. This suggested “warm shallow water with seagrass beds” to the authors, a view supported by other fossils with tropical and subtropical connections.

Bharatisiren was the first fossil dugong from the Indian Ocean (Bajpai and Domning 1997). A cave expedition in the remote Hindenburg Range of the New Guinea Highlands, Papua New Guinea, recovered sirenian bones, though its genus could not be determined (Fitzgerald et al. 2013). Several parts of New Guinea were underwater at that time, and major geological activity (including mountain formation) was yet to come (Toussaint et al. 2021).

The Old World Rytiodus appears closely related to the Pliocene Corystosiren of the New World, with a still-undescribed Miocene species from South Carolina possibly bridging the gap (Domning 1990). This suggests that migration across the Atlantic was still happening at this time. Domning (1989b) suggested that Dioplotherium allisoni could be “directly ancestral to Xenosiren,” though Bajpai et al. (2010) thought Xenosiren might have come from Bharatisiren or Kutchisiren. Rytiodus (from Libya), Corystosiren, and Xenosiren all had large blade-like tusks that may have been used to dig up tough seagrass roots (Domning and Sorbi 2011).

Diversification led to a variety of ecological systems, with diferent types of sirenians living in the same area. These mixed sirenian communities were not random—there were clear differences in their physical traits and feeding habits, suggesting different foraging areas and feeding behavior (Vélez-Juarbe et al. 2012). In the Old World, large-tusked Rytiodus is often found in deposits with small-tusked Metaxytherium (Domning and Sorbi 2011). Samonds et al. (2019) noted that Madagascar had a variety of sirenians living at the same time, as is commonly seen elsewhere in the world. De Toledo and Domning (1989) wrote, “Miocene sirenian faunas on the Atlantic coasts of South America displayed a diversity comparable to those in North America.”

Metaxytheriinae: The genus Metaxytherium was common during the Miocene, with large populations in the Mediterranean and the Caribbean. Domning and Pervesler (2012) suggested that the Metaxytherium species in Europe and North Africa during the Miocene and Pliocene formed a single, evolving lineage. A typical species, like M. medium, was an ecological generalist, living in tropical to warm temperate shallow waters and feeding on seagrass. Metaxytherium serresii was found in the Late Miocene to Early Pliocene in France, Libya, and Italy, with a reduction in size possibly caused by changes in salinity and sea level, which affected the quality and amount of seagrass available for food (Carone and Domning 2007).

In the New World, from the Miocene to Early Pliocene, Metaxytherium calvertense had a very extensive range. “The Central American Seaway, open during the Miocene, permitted M. calvertense to range throughout the continuous zone of warm, shallow marine waters extending from Maryland to Peru” (De Muizon and Domning 1985). It wasn’t long before they disappeared, however. As Domning (1988) noted: “It may be . . . that immigration of competitively superior South American manatees into North America by the late Hemphillian led to extinction of the dugongids; or the manatees may simply have moved into a vacuum left by the dugongids’ demise. In any case, Metaxytherium followed into extinction several other West Atlantic dugongid lineages that had similarly and independently evolved strongly downturned spouts suited to bottom-feeding. However, the abundant seagrasses on which such animals undoubtedly fed persist in Florida to this day. Why bottom-feeding so often proved to be an evolutionary dead end for them remains an unresolved paradox.”

Metaxytherium appears to have left a genetic legacy, though, De Muizon and Domning (1985) suggested, as Metaxytherium may have given rise to Dusisiren and the Hydrodamalinae in the Pacific. Aranda-Manteca et al. (1994) noted, “Dusisiren appears to have evolved in the eastern North Pacific from Metaxytherium,” with Metaxytherium arctodites appearing to be a sister taxon of Dusisiren, as it shared derived characters with the hydrodamalines that aren’t found in other Metaxytherium.

Hydrodamalinae: Takahashi et al. (1986) wrote, “Taken at its face value, the Japanese record now indicates that hydrodamaline sirenians first dispersed northward and westward from California in the Late Miocene, after they had evolved the degree of cold-adaptation represented by Dusisiren dewana” as that species could apparently tolerate colder water than D. jordani. There was also morphological change in dentition, with representative stages including the toothed Dusisiren jordani, the intermediate D. takasatensis, and the toothless Hydrodamalis cuestae (Kobayashi et al. 1995).

Trichechinae: Potamosiren first showed up in Miocene Columbia (Suarez et al. 2021): “The early Miocene appearance of trichechines coincides geographically and temporally with the onset of the Pebas Mega-Wetland System. . . .” Trichechine manatees were likely confined to freshwater ecosystems due to the presence of multispecies dugongid communities previously established along the coastlines. After the dugongs in the region disappeared, manatees were able to return to marine environments and expand their range.

Pliocene

The sirenian fossil record for the Pliocene is not as abundant as for the Miocene, but there are a few points to note.

Dugonginae: Two flat-tusked dugongs co-existed in the Caribbean during the Pliocene, Corystosiren and Xenosiren. Domning (1990) noted, “how food resources might have been partitioned between these two is not easy to explain.” Of course, for the creationist model, this period didn’t last long. Pledge (2006) reported an Early Pliocene dugong jaw found in the Loxton Sands of South Australia. This is the earliest true dugong from Australia, and may have been an early Dugong or closely ancestral. The New World dugongine Nanosiren (Miocene and Pliocene) species were the “smallest known post-Eocene sirenians” (Domning and Aguilera 2008).

Metaxytheriinae: Metaxytherium subapenninum was the last sirenian of the Mediterranean Basin and the last and most derived Metaxytherium species (Sorbi et al. 2012). Climatic cooling had apparently led to an increase in body size and tusk size (apparently to obtain more nutritious roots). In contrast, hydrodamalines also grew large, but adapted to algae in cold waters, surviving into historic times.

Pleistocene

Trichechinae: The Pleistocene saw the development of modern manatees. Perini et al. (2020) noted, “At some point during the Pleistocene, the ancestral stock of the three modern species was distributed along the northern South American coast, Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and, perhaps, the large South American rivers systems. During the Pleistocene, the eastern Amazon became savannized . . . losing the capacity to support environments suitable for manatees, but the western Amazon remained largely unchanged, restricting the freshwater manatee populations there.” This may have occurred several times, following significant changes to South American river courses and wetland formation (De Souza et al. 2021), isolating different populations and encouring new and unique species to form in certain areas.

Domning (2005) noted that “early Pleistocene manatees from Florida are more similar to modern T. m. manatus than the late Pleistocene ones [T. m. bakerorum] are.” This is likely due to climatic patterns that set up barriers for gene flow, promoting the endemic formation of the bakerorum subspecies, then removed the barriers, allowing that genotype to be swamped. Domning also suggested that African manatees probably originated from waif dispersal of manatees from the New World. He pointed to such evidence as: a) manatees clearly go back to the Miocene in the New World, b) early Pleistocene manatees from Florida suggest a plausible structural ancestor for African manatees, and c) a nematode found in African manatees appears to be more specialized than a similar species found in New World manatees.

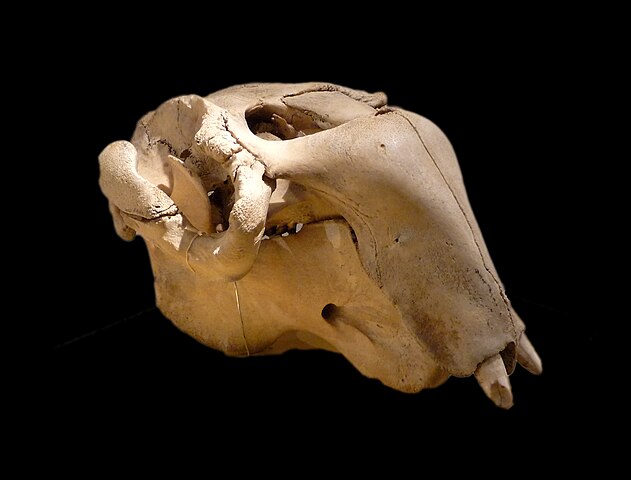

The most significant development in manatees was the dentition. Trichechus has ‘horizontal tooth replacement,’ which is lacking in the earliest true manatee (O’Shea 1994), where, “In each quadrant of the mouth, new molars are developing in the posterior-most portion of the jaw in a continuously active and developing crypt” (Beatty et al. 2012). “Manatees possess only pre-molars and molars (one row on either side of the jaw), but these are continuously replaced by new teeth sprouting at the rear of the row—rather like wisdom teeth—and moving forward. The worn-down front teeth drop out, and the bony tissue separating the tooth sockets continuously breaks down and re-forms to allow the new teeth to move forward at roughly one or two millimeters per month” (O’Shea 1994). So, up to 30 molars develop over the manatee’s lifetime in each of the four quadrants, with the molars erupting posteriorly, shifting forward like a ‘conveyor belt’, until they fall out the front over time. What triggered this development is unknown, though it may involve sediment interaction or abrasive plant fodder. “In contrast to the specialized seagrass grazing of dugongs, manatees are considerably more generalized mixed-feeders, with Trichechus manatus latirostrius reported to consume over 60 plant species in Florida” (MacFadden et al. 2004). Within the Trichechidae, Ribodon shared a number of dental features with Trichechus; not so many with Old World miosirenians. “The geographic gaps between the European Miosireninae and largely neotropical Trichechinae indicate a large gap in the fossil record of this group, one that probably contains many of the anatomical transitions identified here” (Beatty et al. 2012). A plausible developmental lineage would be Potamosiren to Ribodon to Trichechus.

Hydrodamalinae: Hydrodamalis (which included the now-extinct Steller’s sea cow), was completely toothless, and instead “used a pair of broad cornified horny pads to masticate kelp (algal seaweeds)” (Springer et al. 2015). Hydrodamalis gigas was the largest recent sirenian, with one female measured at 7.52 meters (Forsten and Youngman 1982). Hydrodamalines lost both teeth and phalanges. Steller’s sea cow was said, from written accounts, to have had bark-like skin and a thick layer of fat. This led to extreme buoyancy, and it was apparently unable to submerge. In recent genetic research of Steller’s sea cow skin, several genes have been identified that suggested adaptation to cold aquatic environments, forming exceptionally thick blubber and turning off certain genes that might cause a thick, hardened skin layer (Le Duc et al. 2022).

Holocene

Today we have one living species of Dugong, three species of manatee (Trichechus) and a recently extinct species, Steller’s sea cow. Besides their recognized distribution, manatees have been noted in the Pacific, the result of a) intentional introduction in an aquatic plant control program that was soon abandoned, and possibly b) immigration through Panama Canal locks (Guzman and Real 2022).

An Ohio manatee: Williams and Domning (2004) reported on a manatee bone found in gravel pit near Springfield, Ohio, radiocarbon dated at about 2,000 years B.P. There was no indication of wear, so likely no post-mortem fluvial transport. This suggests it was possibly a Holocene alluvial deposit, or there may have been human intervention in bringing it here from a nearby river. Another manatee bone, likely Pleistocene, was found on a gravel bar in the Mississippi River in Arkansas, supporting the idea that the Ohio animal traveled up the Mississippi into the Ohio River and was possibly caught and trapped in the drainage basin after a season of flooding. This particular specimen interests me, as I’m within an hour or so from the quarry it was found (Springfield Sand and Gravel Co., right behind the Clark County Fairgrounds). It’s now owned by the city, but is filled with water, so no further discoveries are likely. It may simply have been a wanderer, as we sometimes see the occasional manatee swim as far as the Chesapeake Bay during the summer months.

Conclusion

The loss of so many kinds of interesting sea cows is one of the tragedies of living in a fallen world. We really don’t know the extent of pre-Flood sirenian diversity, as we only have small glimpse into what survived the Flood.

As the warm post-Flood waters started to cool, it was the dugongs (and the ancestral manatees, whatever they were) that managed to adapt to continuous climatic change and take swift advantage of the expanding seagrass habitat that developed along continents as they continued drifting apart. Eventually dugong diversification peaked and declined, and manatees began to expand out of their South American wetland origin and into marine coastal habitats. One dugong lineage moved into the cold North Pacific waters as it adapted morphologically to the kelp forest, only to disappear forever in the 1700s. Today, only one dugong and three manatee species survive.

Conservation efforts have led to moving the West Indian manatee from ‘endangered’ to ‘threatened’ status, and conservationists continue to work with local people groups in other regions where sea cows live. As part of the Dominion mandate, Christians are called to recognize sea cows as God’s creation, and wisely use our resources and judgment to allow these lineages to thrive and continue bringing glory to the Creator.

Well researched and interesting. however i suggest its wrong. I insist there were no marine mammals before the flood. these sea cows are only post flood adaaptations of kinds that were on the ark. jUst like whales. There are no fossils of them below the k-t line, the flood line for many creationists. only above. They never lived in the preflood seas with those strange creatures. organized creationism must allow and soon enough embrace that breathing milking animatd creatures called marine mammals are just land creatures that took to a post flood empty seas because they are empty of the creatures that were in the seas before .

I have a question about Sirenians.

Are Dugongidae and Trichechidae part of the same species created on the 5th?

I have the same question about proboscideans. Do all the families (living elephantidae) and the extinct ones belong to the same created type or are they different types? It’s something that makes me wonder.

Hello Andres,

As mentioned in the article, Dugongidae and Trichechidae are both part of the order Sirenia, so they’re fairly similar, but they aren’t the same species. Whether they belong to the same created kind is still an open question. Few baraminology studies have focused on sirenians so far, so the jury is still out on that one.

As for proboscideans, baraminology research is also limited. However, one study found evidence of discontinuity within the group, which may suggest that there are multiple kinds represented among proboscideans: Thompson, C., and T.C. Wood. 2018. A survey of Cenozic mammal baramins. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism, ed. J.H. Whitmore, pp. 217–221. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol8/iss1/43/

Thanks for the awesome question!

It’s worth noting that the paper linked in Christian’s reply includes an analysis on Sirenians, which finds Dugongids and Trichechids to fall into the same cluster (and interestingly also finds the legged sirenians to fall outside that cluster).