Rabbits are often one of the first animals that come to mind this time of year. The snow melts. The weather warms. The days are longer. Plant life grows in abundance. And rabbits start popping up like…well…rabbits. These fluffy little creatures are well-known for their ability to procreate. But not only are there simply a lot of rabbits. There are lots of varieties of rabbits. And this doesn’t even touch on the varieties of hares and other rabbit-like animals. The Creator commanded animal life to multiply and fill the earth. The rabbits certainly listened!

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author mentioned, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

Meet the Lagomorphs

Contrary to popular belief, rabbits are not rodents. They actually belong to a completely different order of mammals called Lagomorpha. There are several differences between rodents and lagomorphs, but one of the most noticeable has to do with their teeth. Rodents have two incisors (the teeth located at the front of the mouth) in their upper jaw. But lagomorphs have four!

Not all rabbits are the same. Lagomorpha is a very diverse group of mammals. It contains over 90 living species and another 230 species known only from the fossil record.1 This includes the pika family, Ochotonidae. They resemble tiny, mouse-sized rabbits with little, rounded ears. If you can’t recall the last time you ever saw a pika, that’s because they live in the Rocky Mountains region of western North America and high mountainous areas of Asia. (Although, fossils of extinct varieties have also been found in Europe.)

But we’re not here to discuss pikas. So where do our favorite long-eared hoppers come into the lagomorph picture?

Leporidae: The REAL Rabbits (and Hares!)

Well, alongside pikas, Lagomorpha contains another family called Leporidae. This family contains over 70 living species, all of which we commonly refer to as “rabbits” except one genus, Lepus. You are probably familiar with the cottontail rabbit of the Americas, or the European rabbit if you live across the Atlantic. But also consider the Sumatran striped rabbit of Southeast Asia. You can only find this rare and elusive species of nocturnal rabbit in the forests of a few islands. Species in the genus Lepus are usually called “hares,” notable for their longer ears and legs. One example is the arctic hare, which turns white in the winter to camouflage in the snow. Another is the scrub hare, native to the hot grasslands and savannahs of Africa.

We may not think of rabbits and rabbit-like animals as being very diverse. But they actually come in a wide range of variety. They have also come to dominate a spectrum of habitats.

From Whence the Rabbits Came

Where did rabbits and the various other lagomorphs come from? Evolutionary biologists and paleontologists are not quite sure how or when they emerged. The earliest lagomorph fossils appear abruptly in the fossil record.2 This happens at approximately the same time as most other modern orders of mammals do. Most scientists think lagomorphs evolved from a common ancestor with rodents. Then, these early lagomorphs diverged into two lineages. One led to the pikas, and the other to rabbits and hares.

How should young-earth biologists understand the origin of rabbits? As recorded in the Book of Genesis, God created all living things according to their kinds. This does not mean God created all 230+ species, as the concept of a “species” is a relatively new concept that did not exist at the time Genesis was written. Instead, Genesis refers to these major groups of living things by the Hebrew word min. (We usually translate min into English as “kinds”.) While the exact meaning of min continues to be under discussion, it is at the very least a non-technical term referring to distinct types of organisms. These kinds consist of the groups of original, interfertile organisms God created in the beginning and their descendants.

This makes it very unlikely that God created all species of lagomorphs. But how many created kinds of lagomorphs are there? Did they all come from one created kind or multiple created kinds? In order to figure this out, we use a field of creation science called baraminology, the study of created kinds.

Cluster & Disperse

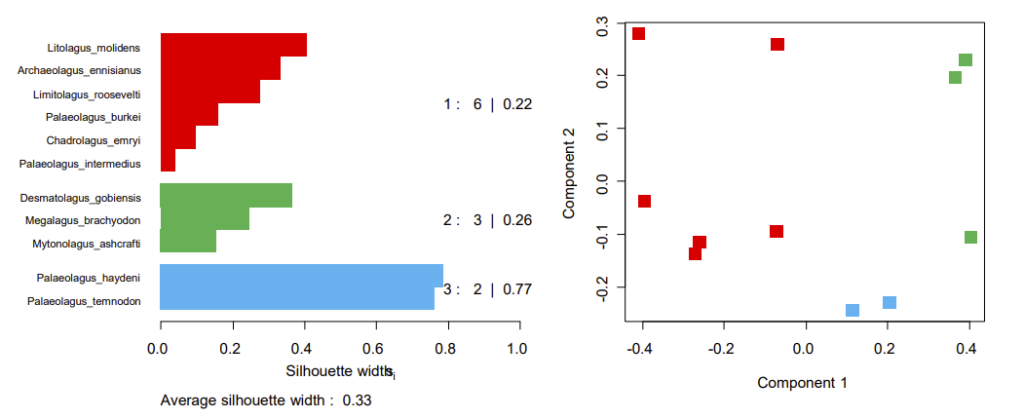

Scientists employ several methods in baraminology to figure out which species belong to the same created kind and which do not. Studies looking specifically at Lagomorpha use a method called statistical baraminology. But how does this method actually work?

When scientifically describing a species, scientists document and publish a dataset. A dataset is a suite of physical characteristics they use to distinguish one species from others. Typically, evolutionary biologists use these datasets to construct phylogenies (evolutionary family trees) in an attempt to figure out how lifeforms diversified from common ancestors.

However, these same datasets can also be used by baraminologists. Datasets from lots of different species can be input into a computer program. This program identifies similarities and dissimilarities between the relevant species. These results are then plotted out in virtual multi-dimensional space. Species that are similar group together, forming a continuous cluster. Dissimilar species do not cluster together; they instead form individual clusters. The clusters represent discontinuous groups of organisms. This means they are anatomically distinct from one another. Their groups are not bridged by transitional species. We think these groups correspond to created kinds.

Here’s the Stats

Hopping into Baraminology

In 2008, CORE Issues in Creation published a study on the baraminology of lagomorphs. The study was carried out by biologist Todd Wood.3 Wood utilized a dataset containing skull characteristics from six genera (the plural form of “genus”) within Leporidae (rabbits and hares). It also included one living and one extinct species of pika. In addition, it included a variety of extinct species that seculars commonly consider either the evolutionary ancestors of lagomorphs, or non-lagomorph species.

His results produced four clusters. One contained both rabbits and hares. A second contained all pikas. The three remaining extinct species comprised the last two groups. From this study, Wood concluded that all rabbits and hares belong to the same created kind. All pikas also belong to the same created kind. However, he points out that his dataset did not include characteristics from anything but the skulls of the species in the study, and his study only included two species of pika. Thus, he was hesitant to draw any firm conclusions about whether or not pikas and rabbits/hares also all belong to the same created kind together.

Another lagomorph study carried out by Wood and C. Thompson and published in the Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism in 2018 yielded similarly inconclusive results.4 The same happened with a recent repeated study by Wood with improvements made to the statistical computer program used, even though other animal groups yielded much clearer results.5

Cracking the Code with Skulls

C. Araujo carried out a fourth study, published in 2021 in the Journal of Creation Theology and Science.6 She used similar methods to Wood and Thompson. However, she applied them to a new dataset that includes 22 species from all major living and extinct groups of lagomorphs, as well as a non-lagomorph mammal, Mimotona. This dataset contained more characteristics than the one used in the previous studies. Unfortunately, it also only included characteristics from the skull. The analysis produced two clusters, but with both rabbit and pika species in each one. It also discovered that some rabbit genera appear to bridge the gap between the two groups. This seems to argue against Wood’s hypothesis that rabbits/hares and pikas belong to two different created kinds. But it does seem to suggest that the created kind to which lagomorphs belong only contains lagomorph species.

Do Rabbits, Hares, and Pikas All Belong to the Same Created Kind?

Several of the conclusions drawn from the studies described above are tentative or inconclusive. However, it is worth noting that they are still informative. All studies demonstrated that, at the very least, all species of rabbits and hares belong to the same created kind. In addition, all species of pikas also appear to belong to the same created kind. What remains for baraminologists to determine is whether or not rabbits and hares belong to a created kind all unto themselves, or whether they make up only part of a much larger created kind that also includes pikas.

Only Part of the Story

One of the recurring problems with lagomorph studies done so far seems to be insufficient data. To create phylogenies, phylogeneticists (scientists who study and create phylogenetic trees) do not necessarily need to document characteristics from the entire body of an organism. This is because they focus on ancestral versus derived traits.

Ancestral traits are characteristics present in a distant common ancestor and inherited by many descendant species. Examining these traits help phylogeneticists identify larger groups. For example, ever-growing incisors is also an ancestral trait. All rabbits and hares share this trait, but similar groups of animals, like pikas, do not.

Credit: James Marvin Phelps – Creative Commons

Derived traits, on the other hand, are new characteristics that developed in a specific lineage after it branched off from the ancestral group. These traits help identify smaller, more closely related groups within a larger group. For example, the long ears many hares have are a derived trait since they do not share this feature with their cousins, the rabbits. In phylogenetics, they generally consider derived traits more informative for establishing relationships between closely related species. This is because they reveal what traits are unique to specific groups. This is why all of the datasets used in the baraminology studies described above contain only characteristics from the skull of various lagomorphs.

A Full-Body Approach to Baraminology

But for a baraminology study, we must focus on a wider range of characteristics. By examining features across an organism’s entire body, researchers can build a more complete picture of how similar or dissimilar species within a group are.

While still entertaining the possibility that rabbits/hares and pikas could be two distinct groups, Araujo hypothesizes that with an even larger dataset and continued study, both rabbits/hares and pikas may be shown to belong to a single created kind.7

Case Study: A Dino Data Dilemma

The importance of using more holistic datasets was illustrated in a recent study by paleontologist Neal Doran and his team on dinosaur baraminology.8 In this study, they compared results obtained from a dataset published in 2004 with datasets looking at the same types of dinosaurs published between 2009 and 2018. They found that datasets with more recent and holistic data tended to provide much clearer and conclusive results. Turning the discussion back to rabbits and their kin, this strongly suggests the problem lies within the current lagomorph datasets and not the method itself.

Conclusion

Lagomorph baraminology represents a particularly exciting area of creation research. Questions remain, like whether pikas belong in the same created kind as rabbits and hares. However, the studies described above also provide us with some of the answers to questions raised by lagomorph diversity.

It appears that after the Flood, all species of rabbits and hares diversified from a single ancestral pair that survived the worldwide deluge aboard Noah’s Ark. And then, as rabbits do today, this pair multiplied as they filled the vacant earth. They became specialized to certain environments, producing the incredible variety we see around us today and in the fossil record.

God instructed the Flood survivors to be fruitful and multiply. It appears the rabbits and hares have done that just fine!

Footnotes

- Caravaggi A. 2018. “Lagomorpha life history.” In: Vonk, J, and T. Shackelford, eds. Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Springer International Publishing. Switzerland. pp. 1-9. ↩︎

- Springer, Mark & Murphy, William & Eizirik, Eduardo & O’Brien, Stephen. 2003. “Placental mammal diversification and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary.” In the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100. 1056-61. ↩︎

- Wood T.C. 2008. “Animal and plant baramins.” CORE Issues in Creation 1:1-241. ↩︎

- Thompson, C. and T.C. Wood. 2018. “A survey of Cenozoic mammal baramins.” In Whitmore, J.H., ed. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism. Creation Science Fellowship, Pittsburgh, pp. 217-221. ↩︎

- Wood, T. C. (2021). Baraminology by Cluster Analysis: A Response to Reeves. Answers Research Journal, 14, 283–302. ↩︎

- Araujo, C. (2020). “Baraminological Study of Mammalian Order Lagomorpha and Stem Lagomorphs.” Journal of Creation Theology and Science Series B: Life Sciences 10:1-8. ↩︎

- Araujo, 2020, Footnote #5. ↩︎

- Doran, N., M.A. McLain, N. Young, and A. Sanderson. 2018. “The Dinosauria: Baraminological and multivariate patterns.” In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism, ed. J.H. Whitmore, pp. 404-457. ↩︎

Good idea and article. I don’t think these creatures are a kind. they must be part of a bigger kind. maybe including Kangaroos. They have bodyplans suited for post fall survival. So this alone shows they don’t look like what thier kind did on creation week. maybe they are in a kind with rodents and opads more. why should god create them? I think creatures on creation week were important and not whims of fancy. i don’t agree dna shows true relationships. Anyways ibce again YES lets squeeze creatures ibro fewer kinds.

+