Judging by the correspondence I received about a previous post on human lifespan, my readers have a great interest in the ages of the Old Testament patriarchs and the genealogies of Genesis 5 and 11. These passages have a special importance to young-age creationists, since it is by adding up the ages recorded there that we estimate how old the earth really is. I was reminded by a reader that these ages also hint at an eschatological importance, since we will be given a new body and live forever in that new body. If we believe that, why is it so hard to believe that we once lived much longer than we do now?

The following article has been reblogged with permission from Todd’s Blog. The views expressed reflect those of the author, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

As a young-age creationist myself, I wish I could say that our understanding of Genesis 5 and 11 is an interpretive slam dunk for young-age creationism. I wish that the passage was clear as a bell, and we know for a fact exactly what it means. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. I still believe in a young earth (for many other reasons), but Genesis 5 and 11 leave me with a lot of really interesting questions. Let me say again that these questions haven’t shaken my certainty in the idea of young-age creationism. I’m merely open to new possibilities about some passages that relate to that belief.

A few days ago I spent a few hours reading up on the genealogies, and I thought it would be good to continue this blog series on human longevity with a summary of some of the questions raised by the many scholars who have written about Genesis 5 and 11. Most of these issues I already knew about, and I can’t say that I have listed all the issues here. There might be more I haven’t come across or forgot about. I think it’s good to remind ourselves of the complexities of even this apparently simple passage. So here we go, in no particular order:

Are the Genesis 5 & 11 Genealogies Complete?

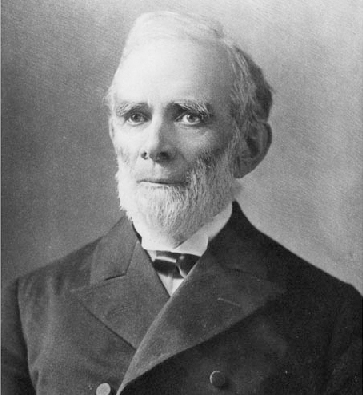

In 1890, Dr. William Henry Green of Princeton Theological Seminary published an oft-referenced article on genealogies and chronology in the well-known journal Bibliotheca Sacra. After comprehensively surveying the genealogies of the Old Testament, he concluded that they were sometimes abbreviated, possibly to make them easier to remember. He is indisputably correct on this point. Compare the line of Aaron recorded in 1 Chron. 6:3-14 with the same genealogy in Ezra 7:1-5. Ezra omits six generations between Meraioth and Azariah. Green takes this to mean that the Hebrew terms for “begat” or “the son of” could include more distant ancestor-descendant relationships than just father/son. If it is the case that the ancient writers of Scripture had a looser understanding of the genealogies than we do here in Western evangelical Christianity, then it is at least possible that some generations might have been omitted from Genesis 5 and 11. Perhaps more importantly, we might conclude this: If genealogies were often shortened as a matter of common practice, then we should not automatically assume that any ancient genealogy is complete.

Is there a Generation Missing in Genesis?

Is there a generation missing in Genesis? If you compare Luke 3:35-36 to Genesis 11:10-20, you’ll see an extra name. Genesis gives the lineage as Shem – Arphaxad – Shelah, but Luke records it as Shem – Arphaxad – Cainan – Shelah. Is this confirmation of Green’s genealogical gaps, or is the extra Cainan just a scribal error?

Are the Genesis 5 & 11 Genealogies Stylized?

If Green is right, we might expect to see that the Genesis genealogies have been altered to make them easy to remember. Some scholars say that that’s exactly what happened: Genesis 5 records the generations from Adam to Noah, and we see that there are ten such generations, ending with a man who had three sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth. In Genesis 11, we have the line from Shem to Abram, which also includes ten generations and ends with a man Terah who had three sons, Abram, Nahor, and Haran. The counting here is a bit muddled, since the ten generations in Genesis 5 must include only Adam through Noah and exclude Noah’s sons, but Genesis 11 has ten generations only if you include Terah’s three sons. Ironically, you get an exact stylistic match if you include the Cainan of Luke 3.

Should We Reject the Idea of Gaps in the Genesis Genealogies Because of the Precise Ages?

This has long been my fall-back argument with presented with claims 1-3 above. The precise formulas followed in Genesis 5 and 11 don’t seem to allow intentional editing while preserving inerrancy. In Genesis 5:15-16 we read:

When Mahalalel had lived 65 years, he fathered Jared. Mahalalel lived after he fathered Jared 830 years and had other sons and daughters.

Genesis 5:15-16, ESV

Now it seems to me that the precise nature of “fathering” or “begatting” isn’t necessarily the important question. Whatever that relationship was, it began when Mahalalel was 65 years old. This level of precision is not found in other genealogies of the Bible, which suggests that the genealogies of Genesis 5 and 11 are unique. Perhaps they do not play by the same rules as other genealogies?

How old was Terah when Abram was born?

Here’s an interesting puzzle related directly to the previous question. Genesis 11:26 tells us that Terah had lived to be 70 when he “he fathered Abram, Nahor, and Haran.” At the end of that same chapter, we read that Terah was 205 when he died in Haran, and the beginning of chapter 12 tells us that God told Abram to leave Haran when Abram was 75 years old (12:4). Now, let’s do a little math. If God called Abram out of Haran after Terah died, then Terah must have been no younger than 205 (Terah’s total lifespan) – 75 (Abram’s age after Terah died) when he fathered Abram. That would make him 130 years old, or sixty years after the age recorded in Genesis 11:26. I think here we have some inescapable evidence within Genesis itself that there’s been some stylistic arrangement to the end of the Genesis 11 genealogy. On the one hand, it doesn’t seem likely that the brothers Abram, Nahor, and Haran are all exactly the same age (although it’s certainly possible given polygamous pregnancies), which suggests that Terah’s age of 70 might only be the age he began to have kids. Since the book of Genesis is about to shift its focus to the story of Abram, it makes sense that the author would put him first in a list of brothers, even if Abram wasn’t the first born. So there is at least a possible explanation, but what does this mean for the other ages given in Genesis 5 and 11?

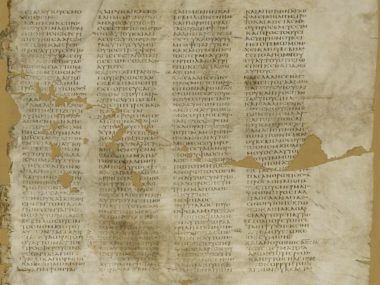

What Ages are the Right Ages?

We have three basic manuscript “versions” of the Old Testament: The Masoretic, the Septuagint, and the Samaritan. The Masoretic is the one that Protestants use today to translate the Old Testament. The Septuagint is an ancient Greek translation, and the Samaritan was an independent Hebrew version of the Old Testament preserved in the city of Samaria (the old capital of the northern ten tribes of Israel). They are mostly the same and definitely tell the same stories, but there are some differences. One of those differences is the ages of the patriarchs. If you add up the ages of the Masoretic, you get 1656 years between creation and the Flood. The Septuagint records 2244 years, and the Samaritan 1307. I suspect some of you might wonder, as I phrased it above, “Which one is right?” I would prefer to ask, “Why in the world are they different at all?” They’re just ages. They don’t seem to impact on important doctrines, so why change them? Is there some significance to these ages that we moderns do not understand?

Are the Ages Symbolic?

A common observation about the lifespans of the Genesis 5 patriarchs is how close they are to multiples of 60. Most of the patriarchs lived more than 900 years, which is 15 x 60. Enoch lives 365, which is close to 6 x 60, and Lamech lives only 777 years, which is close to 13 x 60. This might seem random, except that the ancient Sumerians used a number system based on 60. What exactly this could mean is not clear.

Genesis isn’t the only record of extreme lifespans from the Ancient Near East. The Sumerian King List, known from a number of archaeological discoveries, records reigns of 18,600 – 42,000 years for their earliest eight kings. One interpretation might be that the Sumerians remembered incorrectly a time when people really did live very long lives, but others might say that the cultures of the Ancient Near East assigned unreasonably long lives to individuals as a sign of honor.

These are just a few of the issues that come up when digging into these apparently simple genealogies. I’ll be looking more closely at the genealogies in the coming weeks as we work through these questions together.

Chronology Chronicles Series

Methuselah and Human Lifespan (Part I)

The Primeval Chronology of William Henry Green (Part III)

Well-Night Incredible? (Part IV)

In “The Genesis Flood,” Whitcomb and Morris assumed that there probably were gaps in the genealogies of Gen 5 and 11, and they dated creation week as far back as 10,000 B.C. It has only been since about the year 2000 that creationists favored the no-gap position.