Let’s talk about beavers. As much as any other species, beavers built America. Before European colonization, beaver-made swamps removed giant clearings of trees. The clearings left behind from drained or dried up swamps formed the foundation of campsites, settlements, and even large cities. Beavers supplied more than free tree-clearing labor, though. Their soft pelts drove an entire industry in the new world. Especially in the Pacific Northwest, French, American Indian, and U.S. mountain men made their living trapping beavers to supply the gluttonous demand back East (note I use the word poetically; no one ate beaver pelts). This industry was crucial to driving people west, through treacherous western wilderness.

Due to depleted beaver numbers and change in fashion tastes, the trapping industry fizzled out in the mid-1800s. (Unfortunately, the equally destructive buffalo hunting replaced it.) The late 1700s to early 1800s left beaver populations decimated. At the turn of the century, some eastern populations began to rebound. The west, however, remained tragically beaver-less, to the detriment of the natural landscape (beaver dams are crucial to ecosystems, too). By the end of the 1940s, things looked grim for our flat-tailed rodent friends. It became clear that the only hope for western beaver populations was relocating eastern beavers. So, the question became: how could we transport eastern beavers west to establish new populations? Thus began one of the most ludicrous conservation plans ever attempted.

First, trappers collected some beavers and packaged them in wooden crates. World War II-era planes carried these crates out to the state of Idaho. The pilots would locate a safe area with a beaver-friendly river and no trees in the way. Then, they dropped the crates out of the plane. The crates plummeted, then parachuted to the ground, with the beaver safe inside. After landing, the crate would spring open (or else the beavers would chew their way out) and the confused animals would go about their merry way. Don’t believe me? Check out some found footage of parachuting beavers here. The practice was remarkably effective. New Idaho populations sprouted and dams were built by introduced skydiving beavers.*

Should We Save Nature?

Let’s take a moment to contemplate this entertaining bit of history and get a little philosophical. Though humans deserve almost all the blame for the plight of the beaver, they are also the only species that went out of their way to bring the beaver back. It was not during the peak of the beaver industry that people decided to look out for the beaver, but years after the industry, when beaver demand was comparatively low. This suggests something that goes deeper than simply the preservation of human resources. It seems to support the funny idea that people value the existence of something that does not directly benefit them. They valued nature for its own sake, not because it was a resource. Even if no one needed beavers for anything, most people would still want beavers to survive as a species. Humans might even inconvenience themselves on their behalf.

Let’s not overlook this as a frivolous footnote on the history of the human species. The fact is, not all worldviews justify self-sacrifice of humans on behalf of animals. Especially not for animals that have no direct practical value. Beavers are rather important ecologically, so saving them might make sense even if the pelt industry no longer exists. But there are species that could go extinct tomorrow without harming humans one bit. Why should humans go out of their way to keep these species around?

What About the Lizards?

Consider the Christmas Island giant gecko. This lizard species is endemic, which means it exists on Christmas island and nowhere else. It is also endangered. If this species went extinct, human life would continue the same as always. Our lives would not change in the slightest.

Now, you might be tempted to argue this claim. Lizards are part of an ecosystem, and removing them will cause a domino effect that will, eventually, affect humans, right? Not exactly. Some species do shatter the ecosystem if they are removed. Ecologists have a name for these types of animals: keystone species. But the Christmas Island giant gecko is not a keystone species. In fact, several species of endemic Christmas Island lizards have already gone extinct in the wild. These include the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink, the Christmas Island forest skink, and the Christmas Island chained gecko. These extinctions, so far, have not affected humans to any measurable degree. So, do humans have any moral obligation to protect the Christmas Island giant gecko from the same fate?

Utilitarianism and the “Leave Nature Alone” Position

Some philosophical camps would argue “no”. Utilitarianism values things for their practical use, and so people who subscribe to this moral standard believe there is no moral obligation to save endemic lizards. Then there is another branch of conservationists that have a different approach. They view nature as separate from the human race, and therefore they think the only way to preserve nature is to stay off its property. We can call this camp the “Leave Nature Alone” (LNA) conservationists. They would also recommend we simply leave the island be and let the lizard sink or swim on its own. And then there are today’s conservationists who tend to believe nature is worthy of being preserved regardless of its impact (or lack thereof) on humans.

Let’s take a closer look at these broad systems of thought. We will begin with utilitarianism and then cover the LNA position. Then we will take a look at the history of conservation and the Biblical position before deciding whether these positions have Biblical or ethical merit.

The American Origins of Utilitarian Sustainability

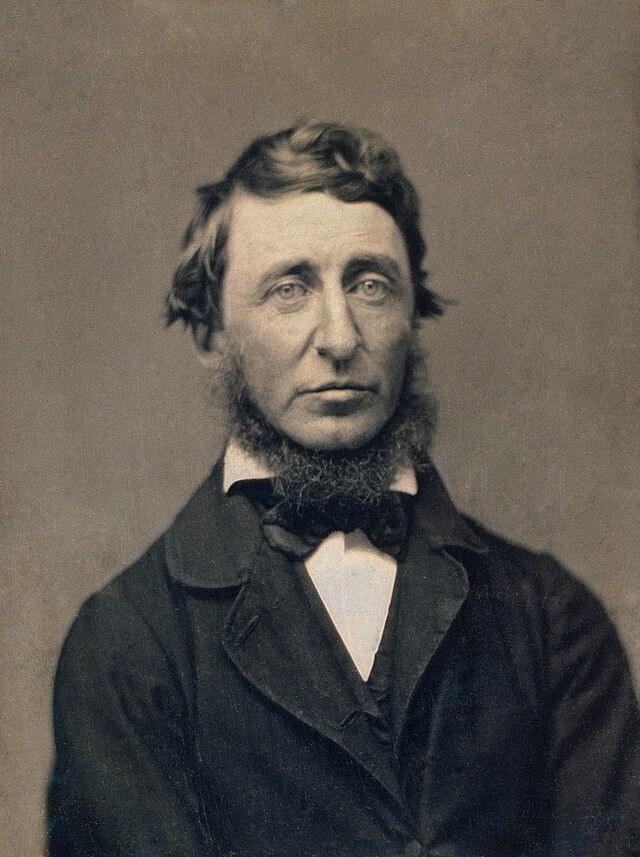

We begin with the position of utilitarianism. This mindset places value on things only because they are pragmatically useful for the human species. We observe this approach best in American colonial expansion in the 19th and 20th Centuries. One of the things that separated American culture from the European ideals of America’s forefathers was the idea of private land ownership. People grew up learning to farm from their parents. They then moved to find new land to claim and own for themselves (an opportunity unheard of in colonized Europe). This is what drove American citizens westward, into a wilderness of unclaimed land to till. Such a lifestyle came with a need for conservation, or at least regulation. This is where the idea of harvesting resources “sustainably” began. If a family or village took too much land, plants, or wildlife at one time, it hurt their own way of life later on. Their conservation ethic relied on preserving human resources because they were resources. This mindset met an eventual challenge during the Romantic period. At that point, the “Transcendentalists” from Massachusetts defended the preservation of nature on account of its aesthetic beauty. People like Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emmerson believed natural resources were valuable outside of human usage.

Just Leave Nature Alone!

Today, people often argue for conservation without talking about human resources. This probably results from the fact that most of us do not directly cultivate our own natural resources for our livelihood. Instead, they want to save nature because it is beautiful, and no one wants to see animals go extinct. But the pendulum can swing too far the other way. Instead of urging people to use nature sustainably or work to help nature thrive, many people would rather “Leave Nature Alone”. Just back off, they say, nature doesn’t need people to thrive. It needs us to stop destroying it!

Who are these LNA proponents? Well, we can begin with the famous biologist E.O. Wilson. In a book titled “Half-earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life,” Wilson argues for setting aside half of the earth as a protected wildlife reserve. You read that right: one half (50%) of planet earth should be set aside for wildlife; no human activity allowed. While this is certainly the most extreme variation of this idea, we can also look to the paper by H.P. Jones et al., published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. In the abstract, they write, “The lack of consistent value added of active restoration following disturbance suggests that passive recovery should be considered as a first option.”1 While the authors admit that “active restoration” may be necessary in desperate situations, they propose that passively leaving nature to its own devices should be our first option. Their Conservation Plan A is literally no conservation at all. Even David Attenborough, who is no enemy of human conservation efforts, seems to encourage a “leave nature alone” approach in his documentary A Life on our Planet. The Netflix film ends with him standing in an abandoned chemical plant, where animals and plants have returned to dominate the area after humans left. His implication seems to be that if we just pack up and get out, nature will do the rest.

With these two sides in mind (utilitarianism and LNA), let’s look at the history of conservation and see how we got here in the first place. Did we make it this far by actively conserving resources for our own self-interest, or does conservation only require that we stay out of mother nature’s way?

The Legacy of American Conservation

America’s history is steeped in both destruction of natural resources and attempts by people to restore them. Before colonization, the native American tribes had a mixed record on preserving resources, as the American nation would after them. The Indigenous nations famously had a sacred view of wildlife. The plains Indians, such as the mighty Sioux, fine-tuned a balance with nature that ensured the bison they relied on for their livelihood could continue to flourish and thrive.

On the other hand, native tribes were not exactly environmentalists. Their mighty buffalo hunts killed hundreds of bison at a time by chasing them off cliffs and driving them into hidden spears. The plains Indians were also known to intentionally burn whole forests to a crisp, flattening the landscape to allow them to spot enemy tribes from afar. Some historians even believe that if the tribes had the manpower or technology required to mass-harvest their resources, they may have been just as destructive to the environment as the nations that took over after them.

Unfortunately, the European colonists who arrived in the New World had both the ability and the motivation. Before the English colonists were the French and Canadian fur trappers, who caught beavers and then brought the pelts back East to sell them to the colonies. This industry lasted little more than a decade, and soon hundreds of mountain men began looking for the next industry, as beaver populations shrunk to near extinction. The next craze was the bison industry, which sent hunters into a frenzy as people discovered their wonderful furs. This industry is particularly gruesome to look back on, as American hunters would shoot down bison by the thousands, before skinning them and leaving the carcasses to rot (years later, after the bison decomposed, the hunters returned to collect the millions of bones).

It is truly impossible for people today to fully comprehend how vast North American bison herds were. Even after years of mass slaughters by hunters from the East, bison herds were still large enough to delay trains for days as they sat waiting for a herd to pass. Yet, it took under 50 years for hunters to nearly exterminate them. Most people who paid any attention to what was happening in the West assumed extinction was inevitable. But just as impressive as America’s quick destruction of the bison was America’s ability to prevent their extinction in the eleventh hour. What changed? An easterner, eager to see and hunt his first bison, visited the West, and this trip would turn him into the nation’s first conservationist.

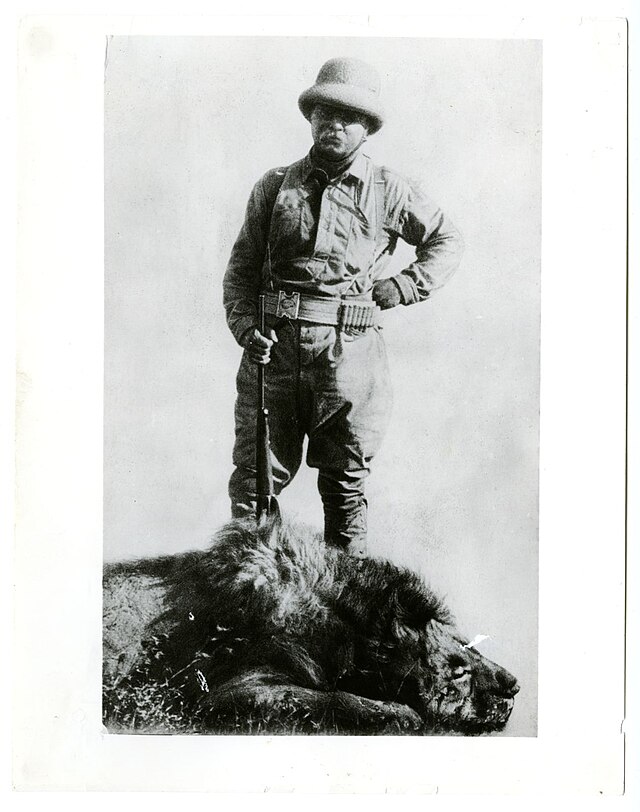

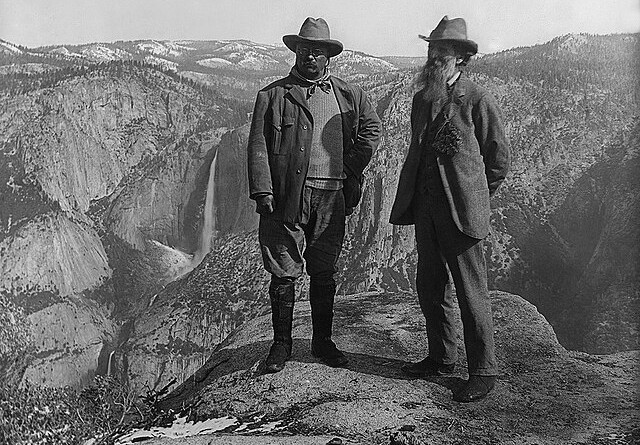

The Cowboy from the East who saved the West

The easterner’s name was Theodore Roosevelt, and he was more of a politician than a frontiersman. He journeyed to the plains in 1883 and hired a guide to help him track down and kill his first bison. For days, the hunt did not go well. Rain fell, the bison tracks disappeared, the guide was in disagreeable spirits, but Roosevelt was in his glory. When they finally came across a herd, Roosevelt fired away and downed his first American buffalo. Though he would go on to become the 26th president of the United States, to him, this hunt was among the greatest moments of his life. Inspired, Roosevelt tried his luck at being a cattleman, but once again, conditions were disagreeable and he struggled to maintain his herd. He returned east to his true specialty, politics. But he never lost his love for the western plains.

Roosevelt knew the western frontier was vanishing. Following the bison industry was the land rush. Thousands of eager families, prospectors, and immigrants raced to claim land for themselves after America transferred swaths of land from native reservations to public land. Roosevelt (and others) feared that, before long, the natural wonders and beauty of the western frontier would be broken into sectors of private ownership. His solution essentially sparked conservation as we know it today. During his presidency, Teddy Roosevelt established five new national parks, setting aside beautiful natural resources for generations of Americans to come.

In the years to follow, other conservation efforts came to life. State, national, and private groups set aside land for bison to roam. Zoos were established to educate and to breed wildlife in captivity. And today, hunters and fishermen pay self-imposed taxes on their ammunition and licenses, funding conservation efforts that keep their game species thriving.

Implications of American History

As you can see, both utilitarian and LNA approaches hit some mark in conservation efforts. Preserving resources humans rely on is a powerful incentive for protective action. On the other hand, the best solution is often to set aside land as reservations for wildlife, suggesting a passive approach to conservation. But throughout this journey into conservation, we have left out one important resource in determining how we should accomplish conservation. It is to that source we turn to next.

Conservation in the Good Book

Conservation is hardly an issue discussed by the church today, especially in the wake of climate change hysteria and environmental activism that most evangelical Christians rarely fall in line with. Common sense tells us that if you believe the world will end with the return of Christ on a date God already knows, you likely aren’t concerned about carbon emissions warming the earth to unlivable degrees. But as we just learned, protecting natural resources has existed since long before the dangers of greenhouse gasses were a hot political issue (pun, unfortunately, intended). While not known for climate alarmism, Christians generally do believe creation is important and valuable and worth some protection. We do not want to see species go extinct or natural resources disappear. But the question remains: are we called as Christians to participate in conservation? To what extent must we care for the natural world?

Believe it or not, there is a Biblical case to be made for a particular approach to conservation. In Genesis 2:15, God created mankind for a purpose, and that purpose is to “work and keep” the garden of Eden. As God’s image-bearer, Adam was expected to nurture the garden. The Hebrew word translated “work” means to “cultivate, till, or enslave,” which reflects the actual labor required to maintain the garden of Eden. But what must Adam work toward? The word translated “keep” means “to guard” or “to protect.” Evidently, God tasked Adam with being a steward or protector over God’s creation. One could even say that Adam was the first conservationist!

Which Approach Actually Works?

This Biblical approach to conservation—an intentional, work-dependent one—is not just the obedient fulfillment of God’s Word. It is also the most effective approach. To measure the effectiveness of conservation, we use the metric of “biodiversity.” Biodiversity requires two things: many different species in a given area, and also a productive number of individuals per species. In other words, neither a grassy field (low species number, high individuals per species) or a fragment of a coral reef (high species number, low individuals per species) is biodiverse. But a rainforest (high species number, high individuals per species) is incredibly biodiverse.

The Leave Nature Alone position recognizes correctly that when humans move into a new area, biodiversity tends to decrease. We build houses, make noises, and clear away lots of plants to make space. Removing humans will certainly help bring biodiversity back. But conservationists often find that if people take the time and effort to “work” and “keep” their gardens—by planting, growing, and maintaining the natural parts of their properties—we can actually increase biodiversity to a degree that is better than before we got there. How profound is that! This approach to conservation can happen in your backyard, and not only is it a fulfillment of God’s first command to man, but it is also better at doing the job than other approaches. It is almost as if God designed creation to exist with mankind, and not apart from it!

The human species cannot leave nature alone. This would be unnatural, since humans have been a part of natural history from the beginning! In addition, this approach is an insult to God’s direct command in His Dominion Mandate, in which God declares that we must have dominion over creation. Finally, nature cannot afford humans simply turning their backs and keeping out of it entirely. Objectively speaking, the best progress towards nature restoration has been human-caused.

A Tale of Two Houses

Imagine there are two houses on a neighborhood street. Both households love wildlife and they want to keep animals and plants coming through their yard. The first house decides that the best way to do this is to do nothing to their land. They refuse to mow the lawn, they block off visitors from walking through their yard, and they dedicate their land to their local wildlife.

The second house, in contrast, is much more active. They purchase and spread mulch. They install irrigation systems. Then, they plant a garden of flowers and vegetables, lovingly care for what they planted, and remove invasive weeds. They even build a birdhouse, a hummingbird feeder, and a birdbath. Which house do you think will have more worms in their soil, more pollinators in their flowers, and more animals passing through their yard?23 And which one more closely obeyed God’s command to “work” and “keep” His creation?

The answer to the conservation question is a straightforward one. Nature needs people to stop thinking of themselves as disassociated with the natural world. Biodiversity depends on people to care for it, nurture it, and—when necessary—drop packaged rodents out of planes. People are God’s representatives to solve real environmental problems and keep flora and fauna thriving. The best response to this important human duty is to go outside, stick our hands in the dirt, and get to work.

Sources

While the history of conservation is easy enough to read about online, I recommend a few books from which my own knowledge of American conservation was collected:

Eager: The Surprising Secret Lives of Beavers and Why They Matter by Ben Goldfarb (2018)

Blood Memory: The Tragic Decline and Improbable Resurrection of the American Buffalo by Dayton Duncan and Ken Burns (2023)

Dreams of El Dorado: A History of the American West by H.W. Brands (2019)

Footnotes

*Unfortunately, there was one recorded instance of a beaver chewing its way out of the crate too soon and falling to its death. In addition, conservationists began to suspect that they were dropping beavers in territories already marked by mountain lions. By targeting open fields where lions were known to roam, they seemed to place the poor beavers in a vulnerable position. Fear of unnecessarily killing beavers led to the practice stopping in the 1950s, despite its mostly successful results.

- Jones, H. P., Jones, P. C., Barbier, E. B., Blackburn, R. C., Rey Benayas, J. M., Holl, K. D., … & Mateos, D. M. (2018). “Restoration and repair of Earth’s damaged ecosystems.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1873), 20172577. ↩︎

- Hostetler, M. E., Klowden, G., Miller, S. W., & Youngentob, K. N. (2003). Landscaping backyards for wildlife: Top ten tips for success. UF/IFAS EDIS. ↩︎

- Larson, Kelli L., et al. “Examining the potential to expand wildlife-supporting residential yards and gardens.” Landscape and Urban Planning 222 (2022): 104396. ↩︎

The turn of the century was in the year 2000. If you mean 1900, kindly say “the turn of the 20th century.”