As biblical creationists, it is important to understand that not all classification systems are the same. Scientists use methods like the Linnaean system or cladistics to group living things based on shared traits or evolutionary ideas. Ancient cultures, including those in the Bible, grouped animals based on how they saw and interacted with them in everyday life. Within creation biology, we use a a system called baraminology. This approach involves identifying the original baramins, or “created kinds,” as revealed in the Bible: the separate creation of individual biological populations and their development of new species over time from Creation to the present day (or so long as they survived).

The following article has been reblogged with permission from Zoo Creation. The views expressed reflect those of the author, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

How creationists might classify living things, has been discussed ever since the modern revival of creationism, e.g. Frank Marsh in the 1940s.1 Specific baraminological terminology developed through discussion primarily between Walter ReMine and Dr. Kurt Wise, which led to publishing separate papers at the second International Conference on Creationism.2,3 ReMine introduced an early system called ‘Discontinuity Systematics,’ but Dr. Wise’s approach to baraminology,4 incorporating young-earth model criteria, has become more widely used (expanded/revised by Wood et al. 2003).5 We now have a robust vocabulary for classification with which to speak about and evaluate ‘created kinds.’

Baraminology focuses on two key ideas: continuity and discontinuity between different living things.6 If two animals share many traits and/or can interbreed (like lions and tigers) they show continuity and likely belong to the same created kind. But if two animals are very different and don’t share these connections (like lions and penguins) they show discontinuity and belong to different created kinds.

Wood and his co-researchers noted that the baramin itself is a “purely theoretical construct,” as it includes all members within a lineage, from its original created population to all descendants that could have developed from them.7 Some traits from that original potential might never have shown up, either because those animals went extinct early on (like during the global Flood) or because they were never fossilized. It is possible that the Fall (the curse on the natural world resulting from Adam’s sin) changed how much of that built-in potential could actually be expressed. So what we see today is likely only a part of what each created kind was originally capable of becoming.

Holobaramin: The full group of known organisms that belong to the same created kind. These are species that clearly share continuity with each other, but show discontinuity with species outside their group. “[T]he complete set of known organisms that belong to a single baramin” (Wood et al. 2003). A baramin would include the holobaramin as well as any related unknown organisms, such as the original population created during the Creation Week.

Monobaramin: All known species of a group that show continuity with each other, but may not include all members continuous with the group. ‘Bears’ and ‘flamingos’ are both monobaramins.

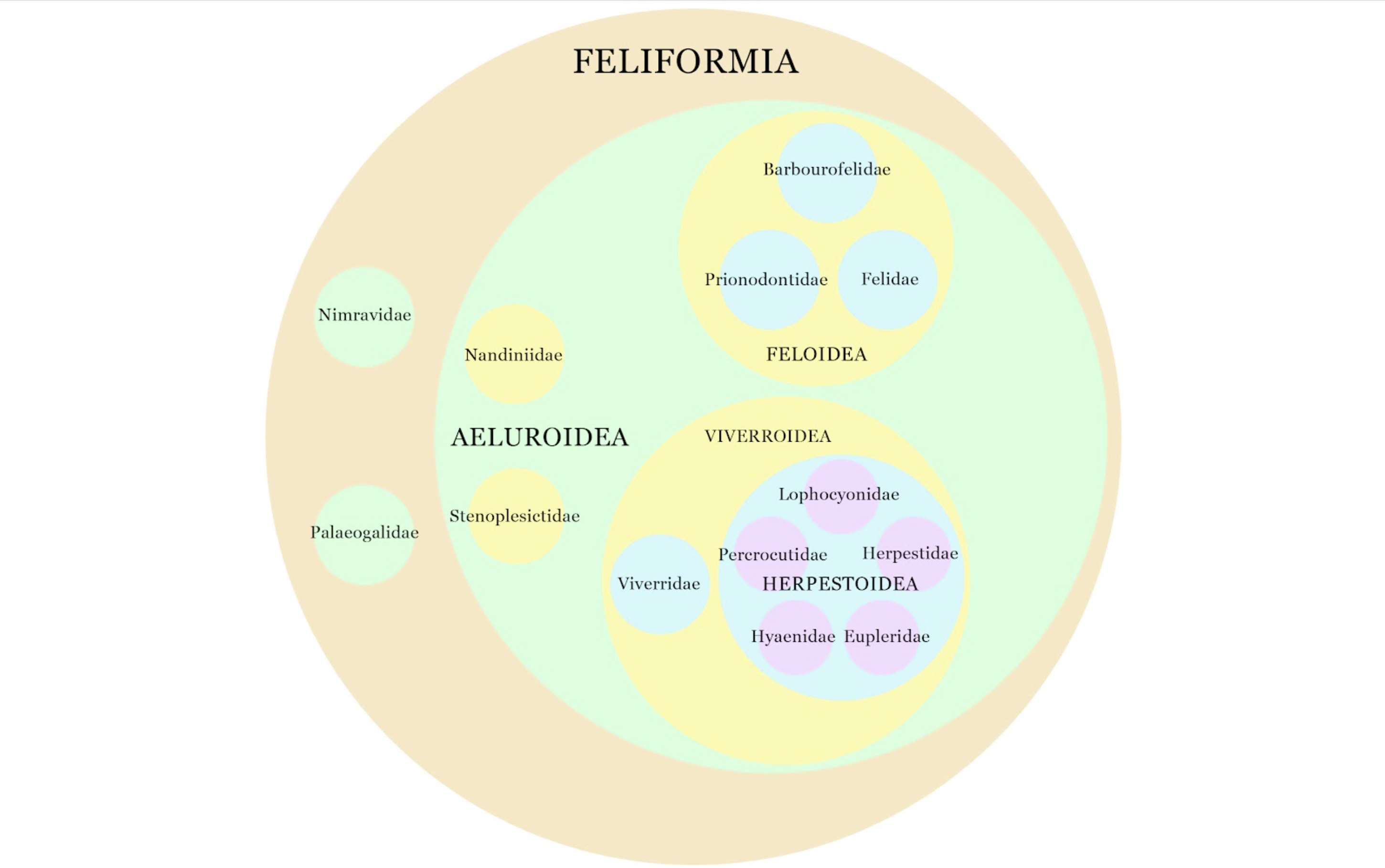

Apobaramin: A group in which all members show discontinuity from another group. It may contain multiple separately created baramins, or may comprise a single holobaramin. ‘Mammals’ and ‘snakes’ are both apobaramins.

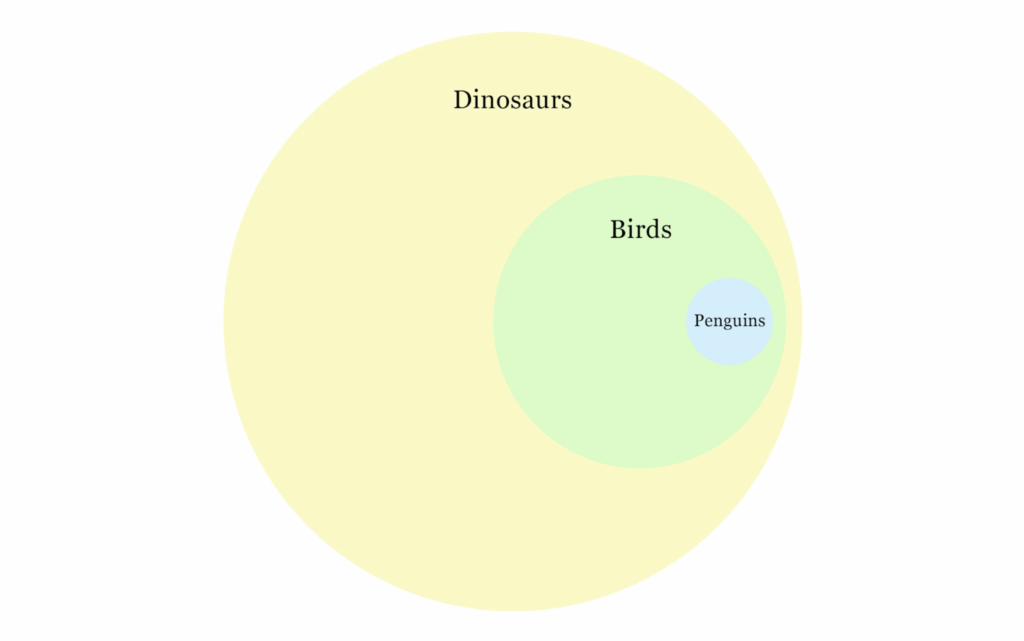

Polybaramin: A designated group with members that share continuity and discontinuity with other members in the group. The group includes more than one separately created baraminic lineage. ‘Birds’ and ‘Dinosaurs’ are both polybaraminic groups.

While creationists use regular scientific classification (e.g. Panthera leo for the lion) within baraminology, scientific taxonomic levels do not directly equate to any of the baraminic levels. Scientific taxonomies used within an evolutionary framework have a prior commitment to universal common descent. Within creation biology, only members of the same baramin share common descent. Creationists recognize patterns in nature even above the level of baramin, but these patterns are not interpreted the same way. Individual groups sharing common descent do not imply that all groups share universal common descent. (That is a fallacy of composition: assuming that what is true for individual parts must be true for the whole.)

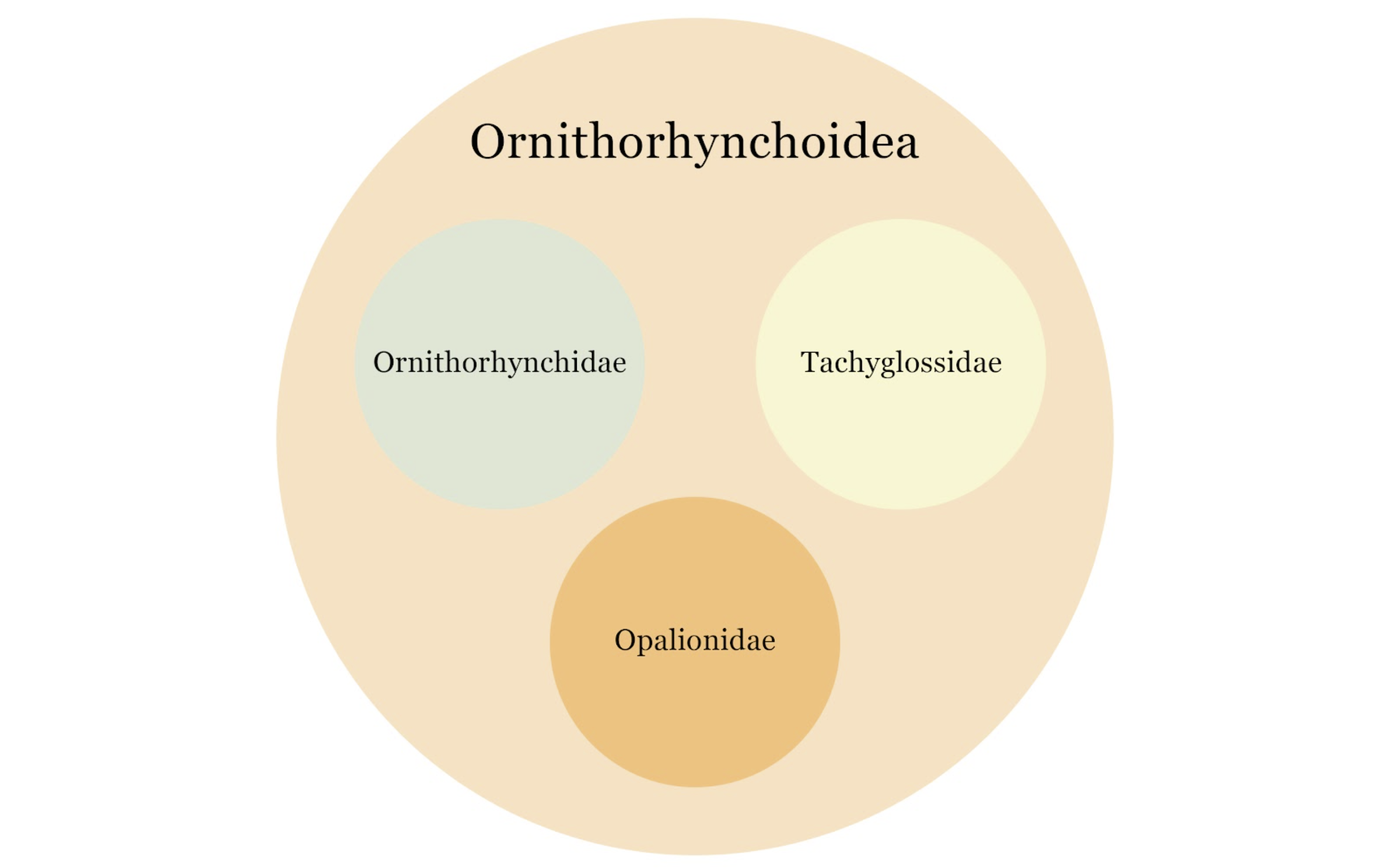

Within popular creationism, some people assume that the taxonomic families of vertebrate animals taken aboard Noah’s Ark, the so-called ‘Ark kinds,’ are the same as holobaramins. This is likely incorrect for most such families. Rather, these families are best considered monobaramins, as the baramin itself may be broader, covering multiple families or even fossil species not incorporated into any known families. Additional examination of the fossil record and other factors will be necessary before any holobaraminic conclusions are drawn. At this point, I’m unaware of any possible examples of an Ark kind made up of only a small part of a family (called a “subfamily”), so I think we can dispose of that idea barring strong evidence to the contrary.

Some created kinds didn’t need to be brought onto the Ark, like certain microorganisms or simple lifeforms that could survive outside it. These groups raise different questions. In some cases, a holobaramin might line up with smaller scientific categories than a family, depending on how much variety (or divergence) has occurred within the group. Sometimes, it is hard to tell if similar organisms actually share a common origin. Robert Carter, for example, has posited several different ‘types’ of baramins, including one for those organisms that are asexual (meaning they do not need a mate in order to reproduce).8 In those cases, the created kind might refer to just a single organism and its exact copies!

Various tools are used to figure out which species belong to the same created kind. These include physical and genetic characteristics, the ability to interbreed, and even cognita, patterns in how lifeforms are recognized or named.9,10 Statistical baraminology is a technical method which looks at large sets of traits and uses math to find patterns, all without relying on prior assumptions about common ancestry.11 A biological trajectory tracks how traits might change over time, based on the evidence we have available.12 No single method is enough on its own. Scientists compare all available evidence together to make the best decision.

Footnotes

- ReMine, W. J. 1990. Discontinuity systematics: A new methodology of biosystematics relevant to the creation model. The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism 2: 207-216. ↩︎

- Remine, 1990 (ref 1). ↩︎

- Wise, K. P. 1990. Baraminology: A young-earth creation biosystematics method. The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism 2: 345-360. ↩︎

- Wise, K. P. 1992. Practical baraminology. CEN Technical Journal 6(2): 122-137. ↩︎

- Wood, T. C., K. P. Wise, R. Sanders, and N. Doran. 2003. A refined baraminic concept. Occasional Papers of the Baraminology Study Group (3): 1-14. ↩︎

- Wise, K. P. 2002. Faith, Form, and Time. Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman. ↩︎

- Wood, et al. (2003) ref 5. ↩︎

- Carter, R. 2021. Species were designed to change, part 3. CMI https://creation.com/species-designed-to-change-part-3. ↩︎

- Sanders, R. W., and K. P. Wise. 2003. The cognitum: A perception-dependent concept needed in baraminology. The Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Creationism 5: 445-456. ↩︎

- Lightner, J. K., T. Hennigan, G. Purdom, and B. Hodge. 2011. Determining the Ark kinds. Answers Research Journal 4: 195-201. ↩︎

- Wood, T. C., and M. J. Murray. 2003. Understanding the Pattern of Life. Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman. ↩︎

- Wood, T. C., and D. P. Cavanaugh. 2003. An evaluation of lineages and trajectories as baraminological membership criteria. Occasional Papers of the Baraminology Study Group 2: 1-6. ↩︎

important subject and good summery. What a kind is is difficult to figure. there must be a snake kind and the two birds on the ark seem to be two kinds There must be a primate kind. Otherwise we should presume there were few kinds created in creatures or insects or sea creatures. organized creationism should be more embracing to squeeze critters into fewer kinds. theropod dinos should be seen only as birds. Bears, wolves, seals should be in a kind amongst others. Weasels cats civets etc should be amongst a kind. Classification should be on kinds and then squeeze them in. There was not that much room on the ark.