Covered in thick, armor plating, the ankylosaurs were built for defense. Even the mighty Tyrannosaurus would have thought twice before dealing with this dinosaur. Ankylosaurs came in a much wider variety of shapes and sizes than we often think. A closer look at the fossil record of these incredible animals has remarkable implications for what the world before the Flood was like and how different animals responded to a world that was actively trying to eat them.

The following article is a summary of the research pertaining to “The Ankylosauria: A Bottom-Heavy Holobaramin?” by Neal Doran and Matt McLain. The views expressed reflect those of the authors mentioned, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

What are Ankylosaurs?

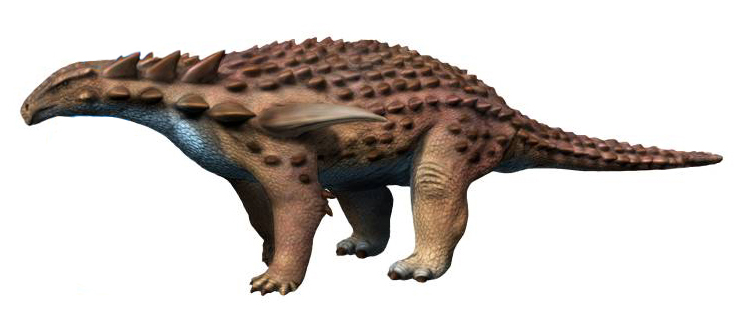

Ankylosaurus itself was a large, bulky dinosaur known from fossilized remains found between the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains. In 1908, American paleontologist Barnum Brown assigned its name, which means “fused lizard”. This referred to how the bones of the skull and other parts of the body fused together, helping to strengthen them.

Though measuring between 20 and 26 feet long and weighing 5.3 to 8.8 tons, it would have had few natural predators. Any predator brave or foolhardy enough to mess with Ankylosaurus had to contend with its armor plating and the large club on the end of its tail. Ankylosaurus swung this weapon at attackers, dealing fatal injuries if not instantaneous death. For all of its defenses, Ankylosaurus was not a predator. It had rows of tiny, leaf-shaped teeth behind its broad, beaked muzzle. This suggests the animal was a non-picky browser, feeding on a smorgasbord of ferns and low-growing shrubs.

Ankylosaurus was only the largest of a very diverse group of dinosaurs called Ankylosauria. There are two families within Ankylosauria. Ankylosauridae is one of them, and it contains species very similar to Ankylosaurus itself, such as Euplocephalus, Saichania, and Zuul (yes, named after the Gatekeeper of Gozer as featured in the 1984 film Ghostbusters).

Nodosaurs

You might have seen portrayals of Ankylosaurus in books or films with sharp spines running along its sides. We know from fossils that the real animal did not have these (nor did it need them!) We actually find this trait in another group of ankylosaurs called the Nodosauridae. Species within this group did need sharp spines for defense because, unlike Ankylosaurus, they had no tail club. Their jaws were more narrow, suggesting they were pickier than their club-wielding brethren. Members of Nodosauridae include Gastonia, Edmontonia, and Borealopelta.

An Armored Kind of Dinosaur

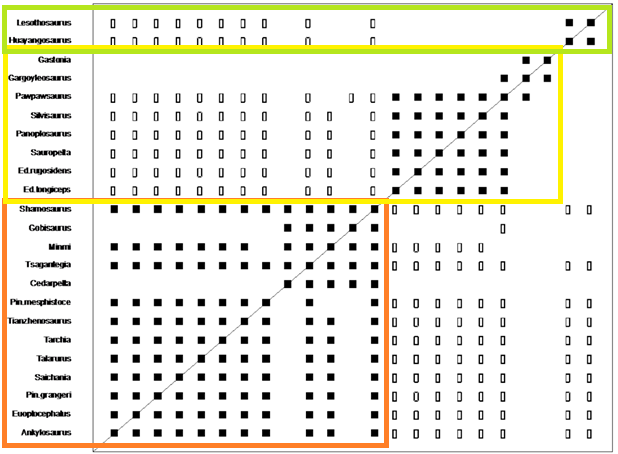

The Book of Genesis records that God created animal life according to their kinds. Each created kind would have diversified, giving rise to many different species. In order to try and figure out which species belong to which created kinds, young-earth paleontologists use a method called statistical baraminology. At the discovery of a new species, scientists develop a lengthy list of traits that they think distinguishes their new species from similar species. Researchers can then put these species and their distinguishing traits into a computer program that compares their similarities and dissimilarities. Species that are more similar to each other will cluster together, while species that are more dissimilar from each other will disperse.

In two recent studies, paleontologists Neal Doran and Matt McLain attempted to figure out how many created kinds of Ankylosauria there were.1,2 Both found that Ankylosauria can split into approximately two groups: Ankylosauridae and Nodosauridae. Both groups are sufficiently distinct from the next most similar dinosaurs, like the stegosaurs. While this might suggest there are two created kinds of Ankylosauria, there is a fly in the ointment, and it is called the Polacanthinae.

Puzzling Polacanthines

Polacanthines are a subfamily within Ankylosauria, and they have been tricky for paleontologists to classify. Species within this subgroup, including Gastonia, Gargoyleosaurus, and Hungarosaurus, do not cluster neatly with Ankylosauridae or Nodosauridae. Instead, they sit firmly in between the two groups. This actually makes a great deal of sense. Polacanthines have traditionally been quite difficult to classify because they possess a combination of features. Some of their traits are more similar to Ankylosauridae, while others (like the lack of a tail club) are more similar to Nodosauridae.

These results provide an interesting contrast from other analyses investigating “intermediate” species. For example, australopithecines are a group of upright-walking primates that combine human-like features with those more atypical of non-human primates. Despite this, statistical baraminology studies have shown that australopithecines do not cluster with humans, or other primates for that matter. They appear to be their own created kind of primate. We can say the same of the so-called “dino-birds,” like deinonychosaurs (such as Velociraptor). These animals share many features in common with birds and non-avian dinosaurs. Again, deinonychosaurs appear to belong to their own created kind.

Rather, polacanthines are an interesting callback of statistical baraminological studies of the fossil record of horses. For a time, creation scientists considered the possibility that there were perhaps as many as three different created kinds of horses. At first glance, this is somewhat supported by the significant dissimilarity between modern horses and small, multi-toed horses such as Hyracotherium, in statistical analyses. However, there are other fossil horses, such as Mesohippus, that appear to bridge the gap between Hyracotherium and modern horses. This suggests that all members of the horse family belong to a single created kind.3

Research on horses and Ankylosauria is important because it demonstrates that statistical baraminology can identify what we should expect to find if a “intermediate form” truly bridges the gap between two proposed created kinds.

Signs of the Curse

These new findings on Ankylosauria provide us insight into the affects the Curse had on some groups of dinosaurs. Before Adam and Eve rebelled against their Creator, there was no death among humans or other animals. As such, we can’t help but wonder why so many animals today and in the past have defensive features. Consider the quills of a porcupine, the shell of a tortoise, even the toxic skin of a poison dart frog. Were these defenses part of their original design? Did God supernaturally change certain animals when Adam and Eve rebelled? Or did they naturally develop these defenses using the genetic toolkit God gave them in the beginning?

The answer is probably unique to specific kinds of animals. But as far as Ankylosauria is concerned, they seem to have developed their protective tail club over time, sometime after the Curse was set upon Creation. Large, predatory theropods like Tyrannosaurus developed sharp, bone-crushing teeth. Some Ankylosauria species seem to have responded by developing weapons of their own.

Other Animals With Tail Clubs

Ankylosaurs, and specifically Ankylosaurus itself, may be well-known for their tail club weaponry, but they aren’t alone. Other other animals have this feature as well. Another dinosaur, called Shunosaurus, was a sauropod (long-necked dinosaur) with a club at the end of its very long tail. Doedicurus was an armadillo-like mammal the size of a car called a glyptodont. It was distinguished from most members of its family by the spiked club at the end of its tail. It looked like a medieval mace. Despite looking like a miniature Ankylosaurus, Meiolania was a large turtle that made its home in Ice Age Australasia. Unfortunately, its cow-like horns and the bony tail club were not enough to save it from extinction, less than 3,000 years ago.

All of these animals belong to created kinds that traditionally did not have a tail club. This suggests that, like Ankylosaurus, the tail club developed after the Curse. The most likely explanation for all of these unrelated animals possessing a tail club is called convergence. This is when organisms develop the same feature or behavior to deal with the same challenge. One study notes a trend that animals tend to obtain tail clubs when they are too large to hide, but too small to avoid predators by size alone.4

Bottom-Heavy Baramin

McLain and Doran believe they have identified the first “bottom-heavy baramin.”5 Baramin is the combination of two Hebrew words meaning “created kind.” But why is it bottom heavy?

In the fossil record, nodosaurs show up from the mid-Jurassic until the uppermost Cretaceous layers of the geologic column. The species within this family tend to be very different from each other. However, this diversity declines the closer we get to the uppermost Cretaceous (hence why it is bottom heavy). Ankylosaurs do not show up until the lower Cretaceous layers. While they also persist until the uppermost Cretaceous, the differences between species within this family are much less than in nodosaurs, but they are more specialized.

Most young-earth paleontologists believe the fossil record ranging from the mid-Jurassic to Cretaceous layers reflect the order in which the floodwaters buried different ecological communities. McLain and Doran suggest this pattern within the nodosaur+ankylosaur created kind might reflect species that lived in different ecological communities adjacent to each other in the pre-Flood world. After the Curse, various populations of ankylosaurs may have adapted to the specific conditions of their ecological communities. Nodosaurs became prominent in Jurassic and certain Cretaceous communities, diversifying into many species. Ankylosaurs became prominent in certain Cretaceous communities. While they did not diversify as much as the nodosaurs did, they did become specialized in defense, developing clubbed tails.

Interestingly, bottom-heavy groups of animals reflect a common trend in the fossil record. Studying this phenomenon more broadly in the future might have some interesting implications for creationist paleontologists.

Conclusion

Further research into Ankylosauria highlights fascinating aspects of dinosaur diversity before the Flood, how they defended themselves from predators, and their implications for the pre-Flood world. The work by Neal Doran and Matt McLain provides valuable insights into how these armored giants fit into the broader narrative of creationist paleontology. And by examining the baraminology of these enigmatic creatures, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate ways in which they adapted to their environments after the Curse.

Ultimately, the continued study of ankylosaurs and other pre-Flood creatures enriches our perspective on the history of life on earth. It encourages us to marvel at the complexity and ingenuity of these ancient animals, reflecting the creativity and wisdom of their Creator.

Footnotes

- Doran, N.A., M.A. McLain, N. Young, and A. Sanderson. (2018). “The Dinosauria: baraminological and multivariate patterns.” In: Whitmore, J.A., ed. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism. Creation Science Fellowship, Pittsburgh, PA, pp.404-457. ↩︎

- Doran, N.A., P.A. Garner, and M. McLain. (2021). “Understanding stratomorphic series.” Journal of Creation Theology and Sciences Series B: Life Sciences 11:2. ↩︎

- Cavanaugh, D.P., Wood, T.C., and Wise, K.P. (2003) “Fossil Equidae: A Monobaraminic, Stratomorphic Series,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5, Article 11. ↩︎

- Arbour, V. M., & Zanno, L. E. (2018). “The evolution of tail weaponization in amniotes.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1871), 20172299. ↩︎

- Doran, N.A. and McLain, M.A. (2022). “The Ankylosauria: A Bottom-Heavy Holobaramin?” Journal of Creation Theology and Science Series B: Life Sciences 12:1-10. ↩︎

This was interesting. Ever since I was a kid, I’ve loved dinosaurs and ankylosaurus was always one of my favorites. I remember having my toy ankylosaurus battle with my predatory dinos. Most frequently my allosaurus. It would always win. The allosaurus would leave and then the ankylosaurus would chew on some ferns. Learning more about them has not only brought back these fond memories, but also somehow made them sweater. Awesome stuff these scientists are doing.

I would like to suggest that an alternative model worth exploring is that the diversity in the fossil record of ankylosaurs and other dinosaurs is a record of post-flood diversification.

The “bottom heavy” observation appears to be consistent with rapid diversification in the early years after they left the ark. The initial burst of diversification then slowed as time passed and led to a reduction in diversity and eventual extinction as they became less able to adapt to the changing climate and associated changes at the end of the Cretaceous.