The Ipuwer Papyrus is an Egyptian manuscript written in poetic form describing a chaotic time in Egyptian history. Biblical scholars have suggested that it describes the plagues preceding the Israelite exodus from Egypt. Secular scholars who do not believe that the plagues were historical events cannot accept such an interpretation, and offer other explanations for the events described in the Ipuwer Papyrus.

The following article is a summary of The Ipuwer Papyrus and the Exodus by Anne Habermehl, and of the surrounding discussion and research pertaining to it. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of New Creation.

In a 2018 research article, Anne Habermehl suggests that “this ancient document most likely describes Exodus conditions; and that the Ipuwer Papyrus therefore offers strong extra-biblical evidence for a historical Exodus.” She goes on to propose that the Ipuwer Papyrus supports a divergence of the biblical timeline from that of the commonly accepted secular timeline by several hundred years.1

What is the Ipuwer Papyrus?

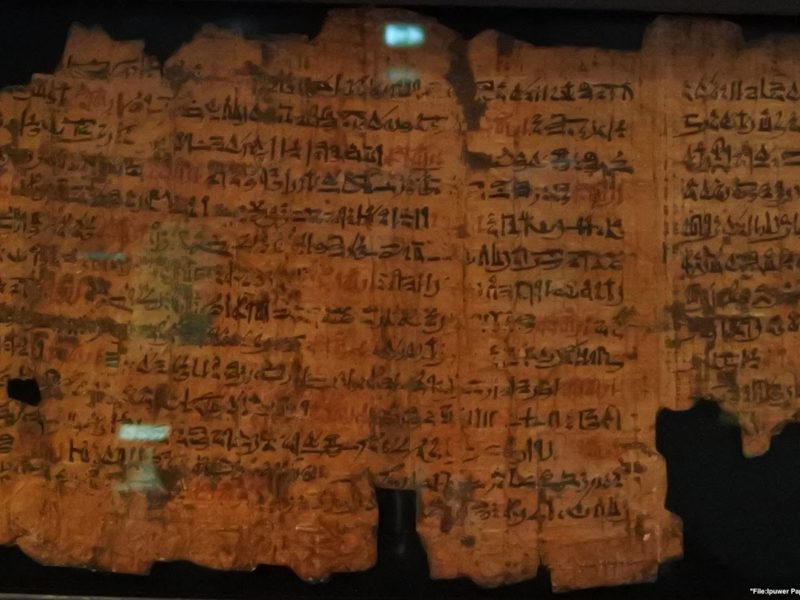

The Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, Netherlands currently houses the Ipuwer Papyrus. The document measures 378 cm x 18 cm. It is written in hieratic script. Hieratic script is a form of ancient Egyptian writing related to hieroglyphics. While hieroglyphics are symbols engraved in stone, hieratic script appears on papyrus documents. Papyrus is an ancient form of paper made from the inner pith of papyrus plants.

The document has sustained some damage, and both the beginning and the end are missing as are some words throughout the text. This presents some problems with translating certain portions of the text, but the majority of the document is readable.

Who were Ipuwer and “The Lord of All”?

The Ipuwer Papyrus records a poetic conversation between an Egyptian named Ipuwer and someone named “The Lord of All.” The name Ipuwer appears in records throughout Egyptian history. In particular, a royal scribe named Ipuwer lived in Egypt’s 19th dynasty (1292–1189 BC). His title, “Overseer of Singers,” suggests this may be the same poet scribe who wrote the Ipuwer Papyrus. Most scholars believe, however, that the poem is copied from a much earlier document.

In the poem, Ipuwer addresses The Lord of All. Scholars have debated whether this refers to the pharaoh or an Egyptian deity. Since the Egyptians regarded pharaoh as a god, the poem could refer to him, but the title The Lord of All appears most often in reference to a deity.

Habermehl suggests that if Ipuwer wrote the poem shortly after the exodus, it cannot reference the pharaoh, since the pharaoh died in the Red Sea, and it is uncertain how long it took to enthrone his replacement. However, not all biblical scholars agree that pharaoh died in the Red Sea.2

Habermehl further argues that a scribe would hardly dare to write something that cast a poor light on the pharaoh lest he face the wrath of the pharaoh. Since the Ipuwer Papyrus is not complimentary toward The Lord of All, it seems unlikely that the term refers to the pharaoh.

Similarities to the Biblical Plagues

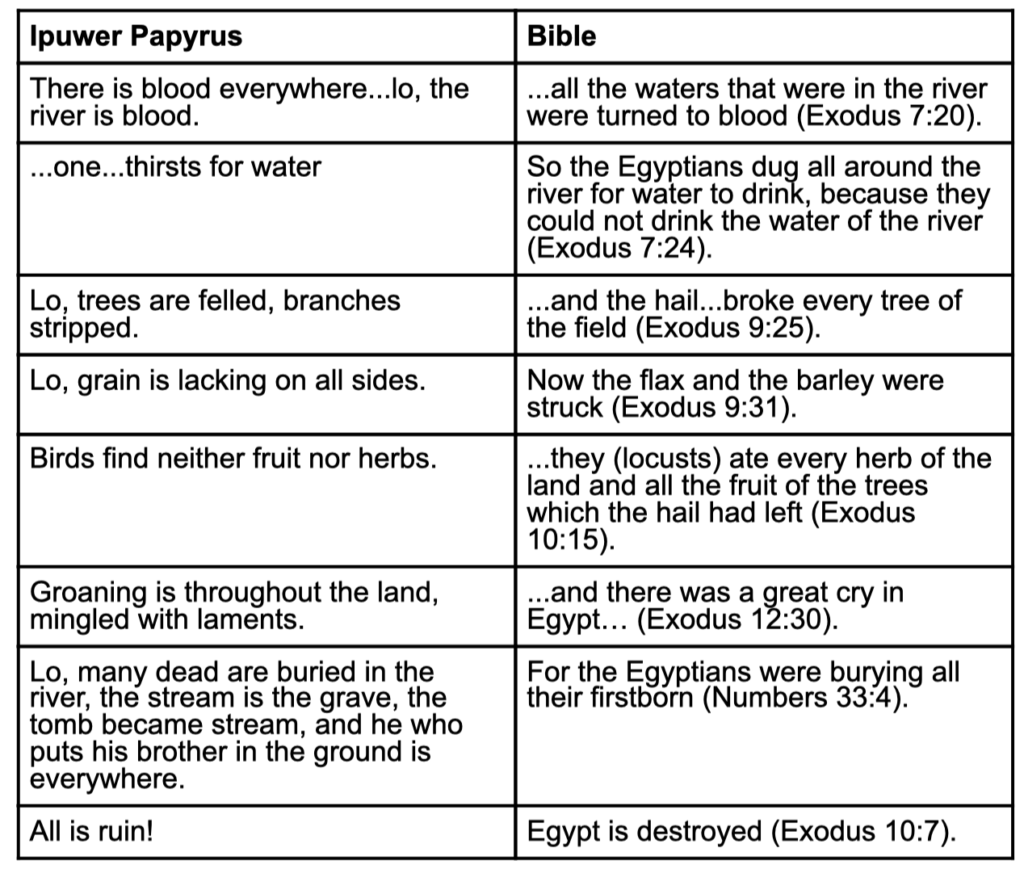

The Ipuwer Papyrus describes Egypt as being in a state of complete chaos and destruction. It states that people are thirsty because the river is blood and that, in a reversal of fortunes, the rich have become poor and the poor rich. There is famine in the land, and even high ranking officials have no food to eat. The fields and trees are barren. Servants are rebelling against their masters, and maidservants are wearing costly necklaces. The following table lists parallels between the events described in the Ipuwer Papyrus and those described in the Bible.

The similarities between the Ipuwer Papyrus and the biblical account of the plagues are striking, but we must establish the date of the papyrus in order to determine whether or not it describes the biblical plagues. The only known copy of the Ipuwer Papyrus dates to the 13th century BC, but scholars agree that it is a copy of an earlier document.

So, When Did Ipuwer Write It?

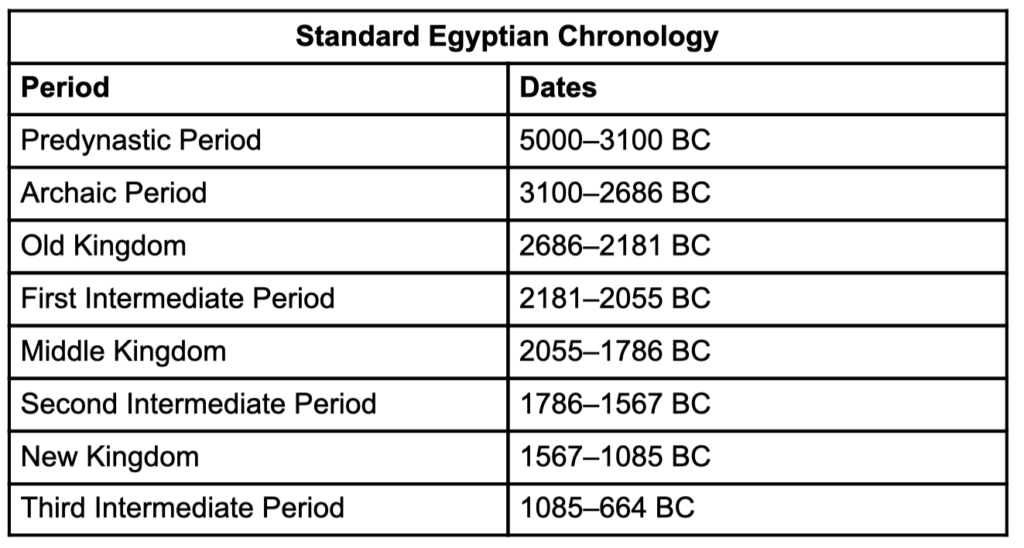

Many scholars suggest that the poem originated in the 12th dynasty, and some suggest that it dates to the 6th dynasty. Both of these suggested dates are based on the fact that these dynasties represent times of political turmoil in Egypt. However, not all scholars agree, and one biblical archaeologist suggests that the linguistic style best matches that of the 18th dynasty, which matches the biblical time frame for the exodus.3,4

In studying the date of the papyrus, Habermehl analyzes the commonly suggested 6th and 12th Dynasty dates, noting that both marked a total collapse of Egypt. The former brought the Old Kingdom to an end, and the latter brought the Middle Kingdom to an end. The collapse of these two kingdoms occurred in a similar fashion, with a series of insignificant rulers followed by an influx of intruders from the Levant. Theban princes, in both instances, restored order.

Two Dynasties or Two Kingdoms?

Habermehl suggests that the 6th and 12th dynasties occurred simultaneously. This theory would explain the similarities between the collapses of the two kingdoms. She bases this idea on the fact that Egypt historically divided into Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt. At times these two kingdoms operated separately, while at other times, one pharaoh ruled both.

Based on her theory, which rearranges Egyptian chronology to overlap the Old Kingdom with the Middle Kingdom, Habermehl suggests that Amenemhat IV of the 12th Dynasty ruled Lower Egypt at the same time as Pepi II of the 6th Dynasty ruled Upper Egypt. She proposes that both of them were pharaoh at the time of the Exodus.

In Habermehl’s view, Amenemhat IV died in the Red Sea. She also believes that the ensuing anarchy in the land resulting from the plagues and the exodus led to the dethronement of Pepi II. According to the Ipuwer Papyrus, “…things are done that never were before. The king has been robbed by beggars…the land is deprived of kingship by a few people who ignore custom.”

Scholars typically date the end of Pepi II’s reign to 2184 BC and the end of Amenemhat IV’s reign to 1777 BC. The biblical date for the exodus is 1446 BC. Therefore, even when Habermehl re-dates Pepi II’s reign to the time of Amenemhat IV, a divergence of several hundred years still exists between the time of these pharaohs and the biblical date for the exodus.

Alternate views

Some biblical scholars who believe that the exodus occurred in 1446 BC in both the biblical timeline and standard Egyptian chronologies reject the idea that the Ipuwer Papyrus represents the events of the exodus. In their view, the Ipuwer Papyrus was composed long before the events surrounding the exodus5. Others ascribe a later date to the document, believing its date corresponds with the biblical date of the exodus.6 Habermehl rejects both of these possibilities.

Many scholars suggest that the collapse of the Old Kingdom of Egypt resulted from a period in which the Nile did not flood sufficiently to irrigate the land. This led to a famine which resulted in the collapse of the Egyptian nation. Yet the Ipuwer Papyrus says, “Lo, Hapi (the god of the Nile) inundates and none plow for him.” It appears that a a drought did not cause the misfortunes outlined in the Ipuwer Papyrus.

Other possible parallels

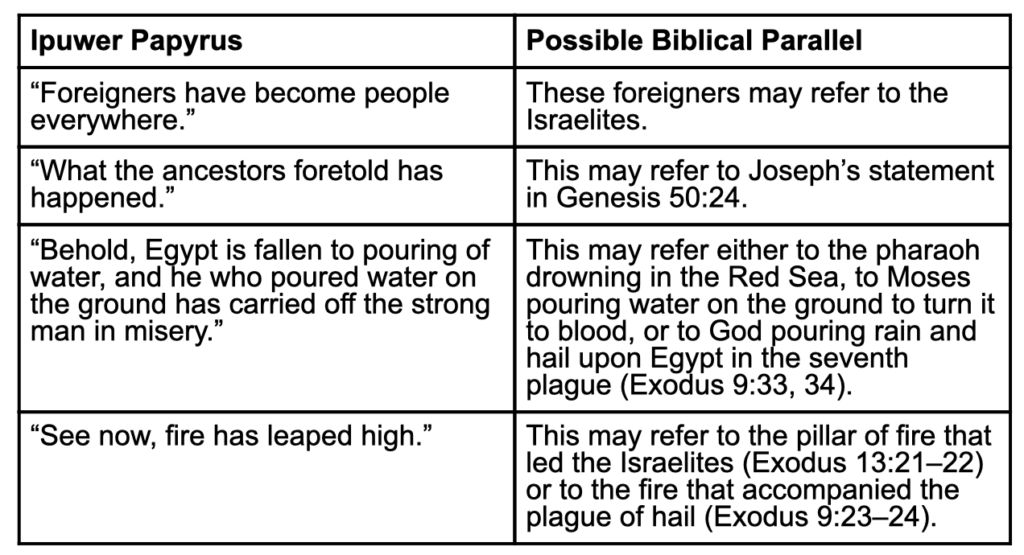

In addition to the parallels listed above, many other statements in the Ipuwer Papyrus may describe events associated with the biblical plagues. The following table outlines these.

Concluding thoughts

Some scholars contend that the Ipuwer Papyrus does not depict real events. Rather, lamentations were a popular form of literature with no connection to reality. Yet the possibility exists that other lamentations also refer to the plagues, since lamentations were popular only for a short period of time.

Other scholars suggest that the Ipuwer Papyrus contradicts the biblical narrative, since it mentions an invasion of Asiatics. Yet it is possible that the decimation of the Egyptian army in the Red Sea allowed for a subsequent invasion by Asiatics.

Much of the Ipuwer Papyrus documents events that do not appear in the Bible. This does not necessarily prove that it does not refer to the plagues. Since it was written from an Egyptian perspective, we should expect it to contain details regarding the effects of the plagues upon the Egyptians, perhaps even describing unfortunate events that followed the departure of the Israelites from Egypt. Since the Bible follows the story of the Israelites, it does not contain details regarding events in Egypt following the departure of the Israelites.

Therefore, if the Ipuwer Papyrus does indeed refer to the plagues and their aftermath, it may shed additional light on the events, supplementing and complementing the biblical narrative. Some of these events include total chaos, role reversals, rebellion, hate crimes, and famine.

The Ipuwer Papyrus has strong parallels with the biblical narrative of the plagues upon Egypt, providing extra-biblical evidence for those events. The date of the Ipuwer Papyrus is important in establishing its connection with the Israelite exodus from Egypt. While various views exist concerning its date, Habermehl suggests that it dates to a concurrence of the 6th and 12th Dynasties of Egypt. She then links these dates to the time of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt.

Footnotes

- Habermehl, Anne. 2018. “The Ipuwer Papyrus and the Exodus.” The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism 8:1–6. ↩︎

- Petrovich, Douglas. 2006. “Amenhotep II and the Historicity of the Exodus-Pharaoh.” The Master’s Seminary Journal 17, no. 1: 81–110. ↩︎

- Kennedy, Titus. 2020. Evidence for the Exodus . I don’t have enough faith to be an atheist blog. March 7, 2020. ↩︎

- Kennedy, Titus. 2021. “The Dialogue of Ipuwer and the Exodus Plagues: Parallels of History or Literature?” Bible and Spade 34, no. 2. ↩︎

- Smith, Henry. 2015. “A Question on Egyptian Hieroglyphs.” Bible and Spade 28, no. 1:3. Turek, Frank (Host). 2020, March 7. “Evidence for the Exodus.” In I Don’t Have Enough Faith to be an Atheist. CrossExamined.org. ↩︎

- Kennedy, 2021. (Footnote 4) ↩︎

This is so fascinating! Thanks for letting us know about it.

Of course, the overlap of the 6th Dynasty and 12th Dynasty is completely ludicrous on archaeological grounds. But why do you not like the end-12th Dynasty model of the Exodus?

On archaeological grounds, this seems the most favorable reconstruction, as according to the most recent research by Ryholt, Sheshi of the 14th Dynasty came soon on the heels of the Amenemhats. His scarabs were found in or near the destruction levels of many MB II sites, which correspond well to the sites destroyed by Joshua.

Hi Andrew,

There are some interesting synchronisms in the 12th Dynasty model, but there are problems with the dating. The standard reading of the biblical dates places the exodus solidly in the 18th Dynasty. For a study on the convergence of the biblical date with the Egyptain date, see Petrovich’s 2006 article: https://www.academia.edu/1049040/_2006_Amenhotep_II_and_the_Historicity_of_the_Exodus_Pharaoh

Regarding the destructions of MB sites in Canaan, it is important to remember that Canaan was a militarily significant zone between Egypt in the south and Mitanni in the north. There are numerous destruction layers at many sites in Canaan. The 19th Dynasty exodus view was based on destruction layers in Canaan, yet it has proven to be inadequate upon further study.

And the books of Joshua and Judges record only three sites that the Israelites burned in the initial: Jericho, Hazor, and Ai (the tribe of Dan later burned Laish). God had promised the Israelites homes that they had not built. For the most part, the Israelites occupied rather than destroyed. Therefore, any time period with widespread destruction in Canaan is probably NOT the time of the conquest.

Hi Abigail,

Thanks so much for taking the time to respond. This is not a good place to hold a debate, but I would like to say a few things about the 18th Dynasty Exodus/Conquest theory.

I have read Petrovich’s article before, and I find it very unconvincing. He relies on the High Chronology which is clearly refuted by the evidence of a shorter reign for both Seti I and Horemheb, and the longer reigns for Amenhotep II and Thutmose IV suggested by Aston (2012) are unrealistic considering that they would require gaps of several decades in attestation for a period otherwise very well attested.

The archaeology of Dr. Wood is unconvincing also. City IV at Jericho, apart from not containing any Bichrome pottery (which he explains away), is missing an entire suite of LB I pottery that appears at other sites. The LB I pottery which he did find originated from the ‘Streak’ above the City IV destruction level (which he admits) and some of it may also come from the Middle Building which is attributed to Eglon of Moab.

And even assuming that Jericho City IV was destroyed near the end of LB I, Wood has yet to explain how Shiloh (founded by the Israelites according to the Bible) was first built in the MB IIB period, or why Gibeon and Arad were unoccupied during the entire Late Bronze Age. The shoddy archaeology of Drs. Wood and Petrovich seems to result from an unfortunate, seemingly religious adherence to the conventional Egyptian chronology.

On the other hand, my personal research of the archaeological literature seems to show that an end-12th Dynasty Exodus produces a suite of matches with the biblical account of history, including Joseph, the enslavement of the Israelites, the building of Pi-Ramesses and Pi-Atum, the Exodus, the Conquest, the later Judges, all the way down to Saul and David in the Amarna age. My chronology is similar to that of Rohl et al., but with a few major differences.

I might add that I used to support the Wood and Petrovich model of Egyptian history, until I began to research the actual archaeological literature myself and correspond with some of the professional archaeologists who have studied these issues.

Regards, Andrew

Do you have a Egyptian chronology that you use? I also agree with a 12th dynasty exodus.

Well written, very interesting.

Thank you!

This is so great! I could use this as a apologetics for my faith. But we must date whenever this timeline is connected to the Exodus era, before some secular historian or Atheist scholar might debunk this, but they need extra-sourse and materials, before they’ll judge.

Thank you for your comment. Hopefully future research will provide clarity on the dating of this artifact.

Wow. Even the mentioning the rich have become poor and the poor rich. There is famine in the land, and even high ranking officials have no food to eat. The fields and trees are barren. Servants are rebelling against their masters, and maidservants are wearing costly necklaces. God said they would plunder Egypt.