One hundred years ago, one of the most famous court cases in American history, the Scopes Trial, took place in the small town of Dayton, Tennessee. The spectacular trial was a flashpoint in the ongoing creation-evolution controversy. Unfortunately, its history is often shrouded in myth and misinformation. In this article, I will chronicle the true story of the legendary case and the lessons we should learn from it a century later.1

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author mentioned, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

What Caused the Scopes Trial?

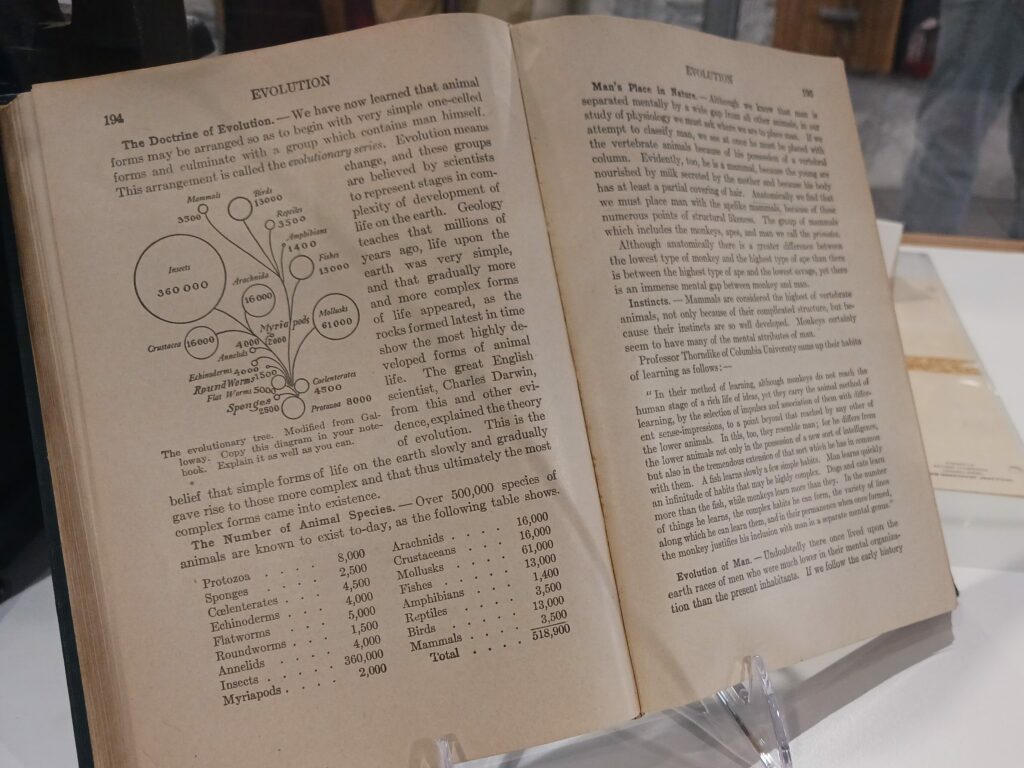

In March of 1925, the state of Tennessee passed the Butler Act. This law prohibited state-funded educational institutions from teaching “any theory that denies the story of the Divine creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” Anyone who violated the law would be subject to a fine of up to $500.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) viewed the statute as limiting academic freedom. They advertised in a Chattanooga newspaper on May 4 for a teacher willing to challenge it for a test case.

The next day, leaders in Dayton met at the local drug store to discuss whether they could bring the case to their town. A case like this, with the nationwide attention it would gather, could help put their struggling town on the map. They asked 24-year old high school teacher John T. Scopes, if he would be willing to be the defendant.

Scopes didn’t normally teach biology. He coached football and taught science at Rhea County High School. The previous year, he had substituted for the biology teacher. Though initially reluctant (and unsure if he had ever actually taught evolution), he agreed to play the part.

What Made the Scopes Trial Famous?

After the ACLU agreed to take up the case, two things happened to ensure the trial became a massive media spectacle.

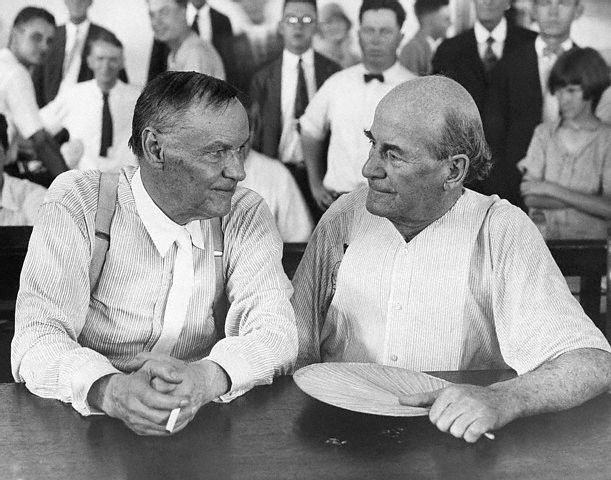

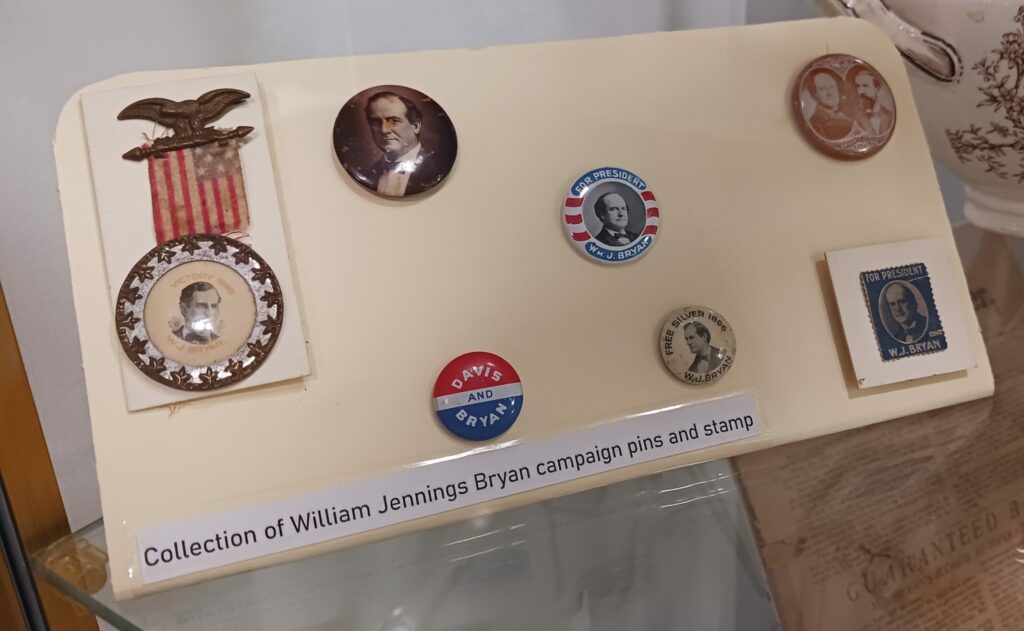

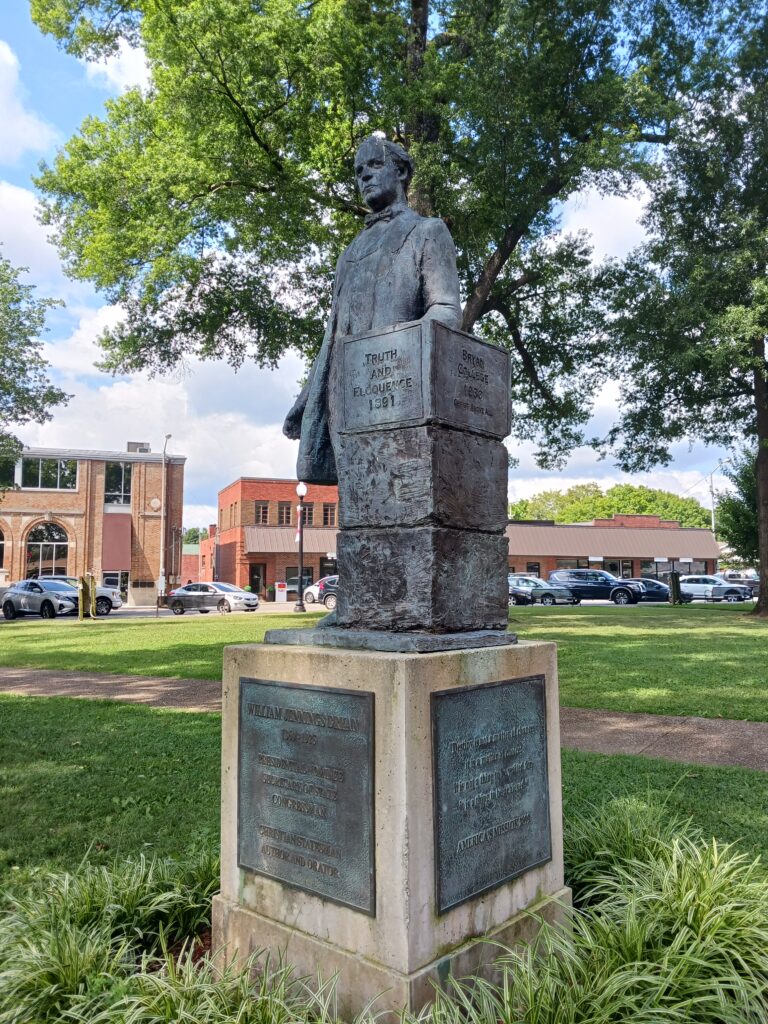

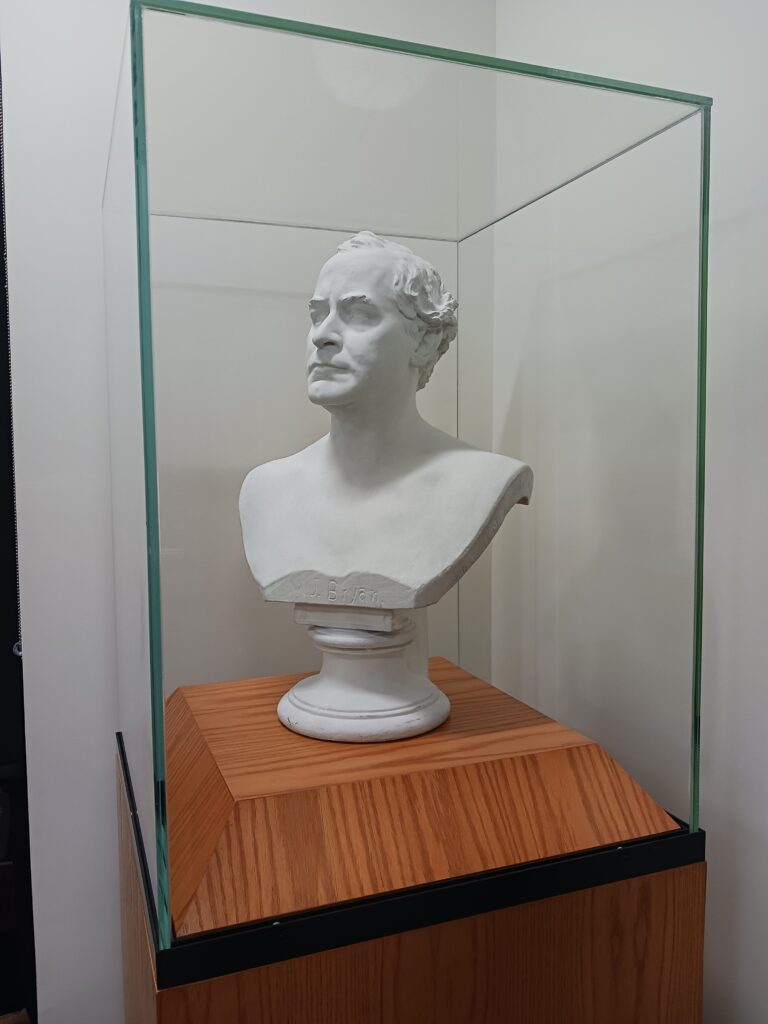

First, the distinguished politician and renowned orator William Jennings Bryan was recruited to help prosecute Scopes. Known as “the Great Commoner,” Bryan was a lion of liberal politics. He had run (and lost) three times as the presidential nominee for the Democratic Party.

Bryan was also an outspoken leader among conservative Christians. He was deeply concerned about the effects of teaching human evolution in public schools, seeing it as robbing schoolchildren of faith in God. He believed that Darwinism’s underlying doctrine of “survival of the fittest” would lead to the oppression of the disadvantaged.

Even before the trial, Bryan crusaded against evolution in his speeches and writings. Now, he had the opportunity to defend a law prohibiting such teaching.

Soon after Bryan joined the prosecution, Clarence Darrow joined Scopes’ defense. Darrow was the most famous criminal defense lawyer in America at the time and a member of the ACLU. Though respected as a brilliant attorney, some at the ACLU were afraid his decidedly agnostic views would turn the trial into a battle royale over science and religion rather than a trial testing the constitutionality of the law.

One thing was for certain: with Darrow involved, things were going to get hot in Dayton—and not just because of the suffocating summer temperatures!

What Happened at the Trial?

The trial extended over nearly two weeks, beginning on Friday, July 10 and concluding on Tuesday, July 21, 1925. Going into the trial, the prosecution’s strategy was simple: show Scopes was guilty of breaking the law, and get a conviction. To do this, they interviewed two of Scopes’ students, the chair of the school board, and the school superintendent. They all testified to Scope’s having taught evolution (again, Scopes wasn’t sure he actually did).

The defense, however, didn’t want to dispute whether Scopes taught evolution. They wanted to try the law. They argued that it unconstitutionally required public school science teaching to conform to a religious standard, namely the Bible. However, the judge found their arguments tenuous and upheld the statute. Darrow and his associates would have to appeal their case to the Tennessee Supreme Court if they wanted to overturn the law.

In the meantime, they would defend Scopes by arguing that while he “taught evolution,” he nonetheless couldn’t have violated the law. This is because, according to their theory of the case, believing in evolution did not require anyone to deny “the story of the Divine creation of man as taught in the Bible”. It only required denial of a literal interpretation of the Bible. Thus, they brought in religious scientists as expert witnesses to testify as to what evolution is and to its supposed compatibility with the Bible.

However, Darrow could only interview one expert witness before the prosecution stopped him. The prosecution argued that the only issue in the case was whether Scopes had violated the law. Therefore, any expert testimony that sought to offer an opinion on whether Scopes had really violated the law would impinge on the legal duty of the jury to make their determination.

The defense responded that the expert testimony would provide clarity on the issues at stake in the trial. In particular, it would clearly define the meaning of both evolution and the Bible. Bryan fired back that the Tennessee law was plain as to its purpose. They didn’t need scientific experts to tell them either the meaning of evolution or the account of man’s origins in Genesis.

Finally, after a full day of debate, the judge ruled that the expert testimony was inadmissible. Written witness statements, however, could be recorded for the appeal.

A guilty verdict for Scopes seemed certain, since the only thing to be determined was whether Scopes had taught evolution, something the defense had willingly asserted. But there was still one more witness that Darrow wanted to interview before the trial was over.

Bryan Called as a Witness

On Monday, July 20, the court moved outside to the courthouse lawn. This lightened the agony of the sweltering heat and permitted more spectators to see the trial wrap up. The audience couldn’t have foreseen the legal theater about to unfold in front of them.

After the written testimonies were submitted, the defense called up “a Bible expert” as their last witness: William Jennings Bryan. Though his co-counsel objected to the move, Bryan willingly took the stand—under the condition he would get to return the favor. What followed was a two-hour game of cat and mouse, with Darrow cross-examining Bryan as a hostile witness.

Bryan Stands His Ground

“Do you claim that everything in the Bible should be literally interpreted?” Darrow asked at the start of his interrogation.

“I believe everything in the Bible should be accepted as it is given there; some of the Bible is given illustratively,” Bryan replied.2 He wasn’t going to fall into the trap of defending woodenly literal interpretations of Scripture.

“But when you read that … the whale swallowed Jonah … how do you literally interpret that?”

Bryan answered, “I believe it, and I believe in a God who can make a whale and can make a man and make both do what He pleases.” When Darrow stated his incredulity, Bryan responded, “When you get beyond what man can do, you get within the realm of miracles; and it is just as easy to believe the miracle of Jonah as any other miracle in the Bible.”

Darrow asked if Bryan believed the sun stood still at Joshua’s command (Joshua 10:12-14). Bryan responded, “I believe what the Bible says. I suppose you mean that the earth stood still?”

When asked if the author of Joshua believed the earth revolved around the sun or vice versa, Bryan stated that regardless of what the human author believed, God, who inspired the Bible, “may have used language that could be understood at that time … [i]nstead of using language that could not be understood until Darrow was born.” At this, the audience laughed and applauded.

As Darrow’s examination drew on, his questions shifted to biblical chronology and ancient civilizations.3 Darrow tried to show that the dates for the Flood and the creation of man calculated from the biblical genealogies contradicted the ages of ancient civilizations determined by modern scholars. Bryan expressed his skepticism about the accuracy of such determinations. “I am satisfied by no evidence, that I have found, that would justify me in accepting the opinions of these men against what I believe to be the inspired Word of God.”

Why Did Darrow Do It?

Calling a prosecuting attorney as a witness for the defense is an unconventional move, to say the least. But interrogating the witness for two hours with dozens of questions that have little to do with the legal issues in the trial prompts us to ask the question that Bryan’s co-counsel, district attorney Tom Stewart was asking: “What is the purpose of this examination?”

Bryan knew exactly what Darrow’s purpose was: “The purpose is to cast ridicule on everybody who believes in the Bible, and I am perfectly willing that the world shall know that these gentlemen have no other purpose than ridiculing every Christian who believes in the Bible.”

To this Darrow retorted, “We have the purpose of preventing bigots and ignoramuses from controlling the education of the United States and you know it, and that is all.”

At the end of the two hours, court adjourned. The trial would be over the next day.

The Outcome of the Trial

Despite the drama of Darrow’s interrogation, the judge ruled that Bryan’s testimony was irrelevant to the case. He struck it from the record. Without a chance of victory, Darrow asked the jury to find Scopes guilty. Within nine minutes, the jury returned the verdict and the judge decided on a minimum fine of $100. Bryan never got his chance to cross-examine Darrow.

Two years later, when the appeal came to the Tennessee Supreme Court, Scopes’ verdict was overturned on a technicality. The case never made it to the US Supreme Court and the Butler Act stayed on the books. The statute would later be repealed by the Tennessee legislature in 1967.

Bryan, after his victory, planned to continue his anti-evolution campaign. Since he didn’t get to make his closing remarks at the trial, he had them published as a separate address. It concluded with a haunting quote from the hymn, “Faith of Our Fathers”:

“Faith of our fathers–holy faith; We will be true to thee till death.”

Five days after the Scopes Trial, July 26, 1925, Bryan passed into eternity during his afternoon nap after church. Five years later, in 1930, Bryan’s legacy was commemorated with the founding of a conservative Christian institution of higher learning in Dayton. They named it William Jennings Bryan University. Today, we know it as Bryan College (more on that at the end of this article).4

“Monkeying Around” with History

The Scopes Trial was a media circus, as Dayton leaders had hoped. Reporters flocked to Dayton from around the country and even Europe. A Chicago radio station broadcast the trial live, a first for the new medium.5 Unfortunately, not all the publicity was good for Dayton. Writers like the famed columnist H.L. Mencken said that it turned the little town into “a universal joke,”6 christening the whole affair the “Monkey Trial.” Despite Bryan’s trust in the “justness of the press” to fairly report his testimony, the media portrayals of his involvement were generally not favorable. Mencken’s were downright acidic.

Later retellings skewed the story, especially the highly fictionalized play-turned-movie Inherit the Wind. They cast Darrow as standing for the cause of science and progress against the supposed intolerance and backwardness of Bryan. This picture of the trial is precisely how Darrow and his allies in the media painted it at the time. Unfortunately, it is still how many Americans see it.

Hopefully, as you’ve read this article, you’ve seen that the truth isn’t nearly as clear-cut as the “Scopes legend” makes it out to be.7

Lessons for Today

In conclusion, what lessons can creationists learn from the Scopes Trial a century later?

First, I think we should admire William Jennings Bryan for his faith, courage, and conviction in the face of opposition. The church in America was at a crossroads in the early twentieth century. Conservative Christians on one side defended the fundamentals of the faith, while liberals on the other sought to “modernize” Christianity by conforming it to the views of naturalistic scientists and historical scholars. Bryan stood stalwartly on the side of biblical inerrancy and the historic tenets of Christianity. He boldly contended “for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3, ESV). He wasn’t afraid to accept the public challenge with Darrow’s questions, but he also wasn’t afraid to admit when he didn’t know the answer.

One aspect of Bryan’s testimony that young-earth creationists often criticize is his willingness to interpret the six days of creation as long periods of time rather than literal, 24-hour days. I do feel that Bryan was inconsistent on this point. However, it is worth mentioning that he didn’t seem to have a strong opinion on the issue either way. While open to an ancient earth, he respected those who held to 24-hour days, including Flood geology pioneer George McCready Price. He was also skeptical of secular scientists when they contradicted a short timescale for human history.

Bryan probably hadn’t fully thought through his own position on the age of the earth, so we should grant him some grace here. The age of the earth just wasn’t of great concern to him. His focus was on affirming the biblical doctrine that God made man in His image with dignity and value over and against the evolutionary doctrine that man descended from the animals by the cruel process of natural selection. As young-earth creationists, we can disagree with Bryan on the importance of the earth’s age. We shouldn’t, however, miss what Bryan was really after. His concerns focused on the effects of evolutionary beliefs on the church and society.

Second, we should remember that God often works in ways we couldn’t have imagined. We see this both in Dayton and in the creation movement at large.

Dayton leaders hoped the trial would attract investors who might help revive their struggling community. Only five years after the trial, they actually got what they wanted. But they probably didn’t anticipate that it would come in the form of a Christian college named in honor of William Jennings Bryan. Today, Bryan College has a significant impact on the community’s economy, culture, and education.8

Beyond Dayton, God has kept the creation movement alive and well for a century after Scopes. All this despite opposition and the perennial mockery of Darrow-like skeptics. In fact, creationism is actually in a far better place today than it was in 1925! At the time of Scopes, there were no science programs at creation-affirming Christian colleges or universities. Now there are several—including at Bryan College!9 There are multiple creationist research organizations and conferences that meet regularly. One example is the annual Origins Conference that just met—at Bryan College.

There are dozens of creationist Ph.D.s in fields ranging from biochemistry to geophysics to vertebrate paleontology to astronomy. If Bryan took the witness stand again today, he would have no trouble finding dozens of Christian scholars to back up his defense of the Bible. When considering all God has done in the last century, I think we have every reason to be encouraged and excited about the next one hundred years of creation!

Footnotes

- My account of the trial is largely derived from that of Larson, E. J. (2020). Summer for the Gods – The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion. New York, New York: Basic Books. Other resources I found helpful in preparing this article include:

Linder, D. (2008). The Evolution-Creationism Controversy: A Chronology. Retrieved from https://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scopes/scopeschrono.html;

A Courtroom Drama. Archives Experience. Retrieved from https://archivesfoundation.org/newsletter/a-courtroom-drama/;

The Scopes “Monkey” Trial. (2023). Retrieved from https://teva.contentdm.oclc.org/customizations/global/pages/collections/scopes/scopes.html.

↩︎ - Except for some minor spelling corrections, the quotes from the trial included in this article are as appears in the word-for-word report The World’s Most Famous Court Trial – Tennessee Evolution Case. National Book Company. Retrieved from https://profjoecain.net/scopes-monkey-trial-1925-complete-trial-transcripts/ ↩︎

- Darrow’s questions throughout the cross-examination were designed to prove Bryan’s ignorance about scientific and historical matters related to the Bible. It is true that for many of the questions, Bryan was not able to provide much of an answer. This is partly why popular accounts often present Bryan as the clear loser in this exchange. However, in fairness, many of Darrow’s questions simply would not occur to most ordinary people. For example, at one point Darrow asked, “Do you know anything about how many people there were in Egypt 3,500 years ago, or how many people there were in China 5,000 years ago?” “No,” Bryan replied. “Have you ever tried to find out?,” rejoined Darrow. “No, sir. You are the first man I ever heard of who has been interested in it.” At this, the audience laughed again.

↩︎ - History. Retrieved from https://www.bryan.edu/about/history/

↩︎ - Monkey Trial. American Experience. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/monkeytrial/#film_description

↩︎ - Mencken, H. L. (1925). Journalist H.L. Mencken’s Account of the Scopes Trial. Retrieved from https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=1077#

↩︎ - The phrase “Scopes legend” is used throughout Edward J. Larson’s excellent book Summer for the Gods, a Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the Scopes Trial. By it, he refers to the standard image of the trial conveyed by popular accounts and Inherit the Wind. Larson spends much time in his book undoing this narrative, though he is not a creationist.

↩︎ - Tucker, B. (2025, July 9, 2025). The 1925 Scopes Trial in Dayton, Tenn. Rhea Herald News.

↩︎ - Ellsworth, T. (2025). Scopes trial propelled Christians toward scientific engagement, professors say. Baptist Press. Retrieved from https://www.baptistpress.com/resource-library/news/scopes-trial-propelled-christians-toward-scientific-engagement-professors-say/

↩︎