The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author mentioned, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

Moses’ Tabernacle: Wilderness Sojourn and Timeline

Exodus 40:17 documents that “In the first month of the second year, on the first of the month, the Tabernacle was set up.”1 Based on that reference, the initial construction and assembly of the components of the Tabernacle took place in less than a year. The Tabernacle was portable, and its construction made it possible to be easily taken down and transported by the Levites during their travels.

The Tabernacle consisted of two covered chambers. The first was the Holy of Holies, measuring ten cubits by ten cubits. The Holy of Holies had a veil to separate it from the Holy Place. The Holy Place, the second chamber, was twenty cubits long and ten cubits wide (Exodus 26). The majority opinion is that the whole of the Moses’ Tabernacle measured thirty cubits by ten cubits.2

The Tabernacle and its components then began a long journey along the “great and terrible wilderness.”3 Its sojourn in the wilderness took place between Horeb in the heart of Arabia and Kadesh-Barnea in the Negev of Judah. Moses’ Tabernacle spent nearly thirty-eight of the forty years in the wilderness at Kadesh, before crossing the Jordan into the Promised Land.4

Movement of the Tabernacle in Canaan

When the Israelites crossed the Jordan into Canaan, one of the first responsibilities of the leader Joshua included finding a place for the Tabernacle. The Israelites needed to find a temporary home near Jericho until a more permanent location could be discovered. The temporary site had to be free from human graves and possible unclean defilement. The ancient sacred area received its name based on a circle of large stones. There are several sites that the late archaeologist Dr. Adam Zertal discovered resembling the shape of a sandal or a foot. This “Zertal-footprint” is meant to symbolize treading and ownership.5 The Gilgalim (“circles”) construction in Canaan dated from very early times, Adam Zertal suggests the early Iron Age.6 Though Gilgal-Jericho’s location is disputed, that location east of Jericho became that brief Tabernacle location.

Once the Israelites had conquered the land, they needed to find a more permanent place for the Tabernacle. Each of the Israelite tribes wanted the Tabernacle to be with them in their land-inheritance.7 Joshua, as the commander, had the authority to choose the location of the sacred shrine. He could have chosen his tribal allotment of Ephraim as a personal privilege. However, Shiloh stood near the border between Manasseh to the east and north, and Dan and Benjamin in the south. This more central location seemed beneficial for all tribes on either side of the Jordan.

According to Joshua 18, the Tabernacle continued in Shiloh after Joshua’s death. It stayed in Shiloh through the time of the Judges. The Tabernacle is still there in 1 Samuel 4 during the days of Eli when the ark of the covenant parted from the Tabernacle. When the Israelites carried the Ark into battle at Aphek/Ebenezer, it was no longer the God of Israel but the physical ark itself in which Israel placed their hope.8 The Philistines captured the ark during that struggle, and Israel suffered a significant loss.

As far as the Tabernacle is concerned, history is silent about Shiloh after the removal of the Ark. According to Dr. Scott Stripling, director of the current excavations at Shiloh, “A second and even more devastating destruction, probably at the hands of the Philistines (1 Sam 4), occurred around 1090 B.C.”9 The Tabernacle was moved or replaced after Shiloh’s destruction and is next seen in the biblical text when David encounters the priests in Nob in 1 Samuel 21. According to 1 Chronicles 16:39-40, the Tabernacle is later set up in Gibeon, about 5 miles northwest of Jerusalem.

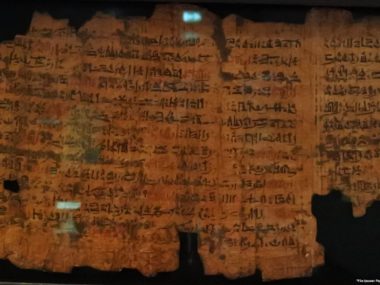

In summary, after Joshua and the Israelite tribes crossed the Jordan River into the Promised Land, the Tabernacle stood at Gilgal for seven years. Joshua 8:30-35 provides documentation that there was an altar built at Mount Ebal where the Israelites renewed their covenant. 10 The famous Abisha scroll, a likely eighth or ninth century A.D. scroll was purportedly written at the door of the Tabernacle at Ebal.11 Richard Meyers also suggests the Tabernacle may have been here for a brief period as well during the time of the conquest. There is a “Zertal-footprint” location at Ebal, as well. The Tabernacle’s permanent home was to be Shiloh, where it would remain through the season of the Judges. It was later set up in Nob and Gibeon. The mention of a tent in 1 Kings 1:39 suggests David’s Tabernacle was in Jerusalem before the building of Solomon’s temple.

The Date of the Exodus and the Duration of the Tabernacle at Shiloh

To determine how long the Tabernacle stood at Shiloh, it is necessary to ascertain the date of the Israelites’ arrival in Canaan. The two main views are the late date Exodus (13th century B.C) and the early date Exodus (15th century B.C.).

The 480 years in 1 Kings 6:1 and Late Date Exodus

1 Kings 6:1 notes that the construction of Solomon’s Temple began 480 years after the Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt. The widely accepted date for the initial construction of Solomon’s Temple is 966 B.C. To make the late Exodus timeline fit the 13th century B.C. chronology, critical scholars and biblical-minimalists translate the Bible to fit that narrative. If the 480 years are part of the equation, there are several possibilities to synchronize the late Exodus with those years.

1) The most common response would be to take the 480 years and make it symbolic of twelve ideal generations. Kenneth Kitchen uses and appeals to the oft-repeated explanation that this figure is not a total time span, but instead, twelve generations made up of an ideal (or “full”, as Kitchen says) generation of 40 years each.12 This way, no matter the dates and ages of reference, the biblical text of 480 years is purely symbolic.

2) The late date Exodus chronology uses the 966 B.C. Temple construction date, though a different interpretation makes the time of the Judges fit within the 200 years of what’s left between 966 B.C. and their 13th century B.C. Exodus date. One assumption is that all the numbers of years noted in the book of Judges are overlapping and are not meant to be a series of years of Judge’s ruling in any form. This explanation requires a loose confederation of tribes that would not have been able to remain unified for very long.

3) Creating a combination of the first two scenarios makes up a third option. An infrequently used fourth option is to disregard the biblical text completely.

By performing these kinds of interpretive textual adjustments, the time between a late date Exodus to the erection of Solomon’s Temple suggests the Tabernacle resided in Shiloh for just over 200 years.

The late date Exodus also allows the dates to include a 19th Egyptian Dynasty and Pharaoh Ramses II as the Exodus pharaoh.

Archaeology and an Early Date Exodus: The Entrance at Shiloh

By using synchronisms in archaeology and the biblical text, an early date Exodus date shows the number of years the Tabernacle survived in Shiloh. There are two significant dates: 966 B.C. for Solomon’s Temple initial construction, and 1100 B.C. for the time of the Judge Jephthah (Judges 11-12). Another known period is the Exodus duration.13 Based on the scriptural and archaeological evidence, the people of Israel existed as a unified nation of peoples longer than the late date Exodus timeline proposes. The time of the judges did have some overlapping of dates as noted in the late date Exodus chronology. This overlapping is most notably at the time of Judge Jephthah and following, not for the entire period of the judges. During these dates, the Israelites are repeatedly engaged by the Philistines, combining the time with Samson, Eli, and Saul.

Given the biblical text of 1 Kings 6:1, and the 480 years noted, it is a simple matter of math to find the early date Exodus timeline. Starting with 966 B.C, and counting back 480 years is 1446 B.C. Subtracting the Exodus duration of 40 years in the wilderness, and seven years of conquering as in the late Exodus chronology leaves a date of 1399 B.C. The second significant date of 1100 B.C. is also synchronized with its mention of 300 years, giving that early start date that Moses’ Tabernacle began to reside in Shiloh.

Archaeology and an Early Date Exodus: The Exit of Shiloh

A biblical synchronism can be used to discover when the Tabernacle was no longer at Shiloh, though is not often used. Jeremiah 26:6 prophetically declares that Jerusalem will be like Shiloh in its destruction.14 A foreign power overtook Jerusalem in 605 B.C. There was a 70-year land Sabbath (490 years) between that initial captivity and the fall of Shiloh.15 By taking the time of David back to Saul, who reigned 40 years, and the time needed for Samuel to be ‘old,’ brings the end-date of Shiloh and the Tabernacle to 1094 B.C.16 When Samuel grew into an old man, Saul became king in 1052 B.C. And since Eli died as an old man, and Samuel had only reached eight years of age when the Philistines captured the ark at the Battle of Aphek/Ebenezer, Samuel needed to grow up, get married, and have his children be old enough to be candidates for replacing him. 605 B.C. + 490 Years = 1094 B.C.

The Danish Excavation

A confirming end date for the Tabernacle in Shiloh for an early date Exodus timeline uses archaeological evidence from excavations at Shiloh. Before his death, the Danish archaeologist Hans Kjaer published preliminary reports on his excavations at Shiloh. For the non-minimalist, his report contained a significant find for students of the Bible: the destruction of Shiloh dated to about 1050 B.C.17 However, Marie-Louise Buhl, keeper of the National Museum of Denmark, who wrote part of the final report on the Danish excavations at Shiloh, disputed this date. She came to a different conclusion, “The collar rim jars from ‘House A’ date from the Iron Age II period, not Iron Age I.”18 She contended that it is “beyond any doubt” that the fire that destroyed House A was at the end of the 8th Century B.C. and not in 1050 B.C.

A Reassesment

Professor Yigal Shiloh, an archaeologist on the staff of Hebrew University who shares the name of the biblical site, later discovered that Ms. Buhl had erred in the pottery dating. Professor Shiloh, who excavated at Hazor, said, “We have checked [Kjaer’s] conclusions with some pottery experts and all confirm the accuracy of his conclusions. None has any hesitation in disagreeing with Ms. Buhl.”19 While the collar rim jar continued in Iron II, as Ms. Buhl noted, the Iron Age II collar rim vessel was a smaller pot. The jars that Ms. Buhl used to date the destruction of Shiloh at a later date reverts to the 1050 B.C. date initially noted by Kjaer. As Dr. Stripling recently noted about Bronze age pottery, “it is not like in [that year] they all had a convention and said, ‘let’s all start making pottery this way’.” The paradigm is the same. There are transitional forms of pottery, and a continuation of types, revealing a process of change.20

This date does not prove that the Philistines destroyed Shiloh, only that there was a destruction layer at the excavation at about that time. Israel Finkelstein who later performed excavations at the same site (1981-1984) also confirms the 1050 B.C Date.21 The archaeological referenced period of 1050 B.C. contains a plus or minus of fifty-year variation establishing the biblical textual reference of 1094 B.C. This year allows an Egyptian 18th dynasty and Pharaoh Amenhotep II as Pharaoh of the Exodus.

Late and Early Date Exodus, Compare with the Seder

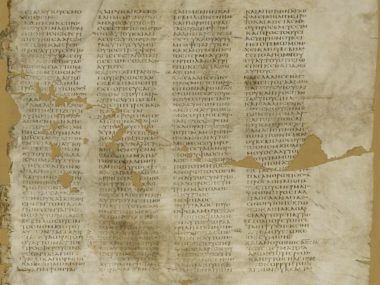

The Seder Olam Rabbah is an ancient Jewish chronicle written about 160 A.D.22 According to Ken Johnsen’s notes from the Ancient Seder Olam, when the Seder gives information with no justification it is meant to be accepted-historical fact.23 The Seder Olam Rabbah declared that Israel worshiped at the Tabernacle in Shiloh for 369 years until the Philistines destroyed it.

The Late Date

If the late date Exodus is correct, the Tabernacle would only have been in Shiloh for about 220 years at the most. Israel would have been a loose confederation of tribes, and the years noted in Judges would have to be translated and justified to fit this number of years. For the late date Exodus, the Seder was off by about 150 years.

The Early Date

The early biblical and archaeological date Exodus has several synchronisms with start and end dates in Shiloh. The Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt in 1446 B.C., a 40 year wandering in the wilderness, and a 7 year conquering period. The Tabernacle placement in Shiloh started in 1399 B.C. (1446 B.C. – 40 years – 7 years = 1399 B.C.) The biblical and archaeological evidence of the destruction of Shiloh at about 1094 B.C. has the Tabernacle in Shiloh for a total of 305 years. Using the early date Exodus, the Seder was only off by 64 years.

Results

Based on this research, the archaeological referenced destruction of 1050 B.C. is less than 50 years different from the biblical chronology of 1094 B.C. for the early date Exodus. The Seder’s proposed number of years in Shiloh miscarries at the period of the Judges in Rabbinical writings.24 The Seder Olam Rabbah is accordingly off by 64 years, based on the destruction level date of 1094 B.C. with the early date Exodus, and the Tabernacle was only in Shiloh for 305 years and not 369 years as reported by the Seder.

References

- Harris, W. Hall, III, Elliot Ritzema, Rick Brannan, Douglas Mangum, John Dunham, Jeffrey A. Reimer, and Micah Wierenga, eds. The Lexham English Bible. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2012. ↩︎

- BAS, Bible Review. Biblical Archaeology Society, 16:06, 2004. ↩︎

- Martin Abegg Jr., Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English (New York: HarperOne, 1999), Dt 8:15. ↩︎

- W. Shaw Caldecott, James Orr, and T. Whitelaw, “Tabernacle,” ed. James Orr et al., The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia (Chicago: The Howard-Severance Company, 1915), 2891. ↩︎

- Ralph K. Hawkins, “Israelite Footprints” Biblical Archaeology Review, 42:2, March/April, 2016. ↩︎

- Adam Zertal, “Cultic Encounters at Mt. Ebal: The Renewed Excavations of the ‘Biblical’ Mt. Ebal Excavations Seasons 1982-1985 and 1993.” In Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan XIII, edited by Hamad Al-Tajir and Burton MacDonald, 623-628. Amman: Department of Antiquities of Jordan, 2004. ↩︎

- Donald Slager, “Preface,” in A Handbook on 1 & 2 Kings, ed. Paul Clarke et al., vol. 1–2, United Bible Societies’ Handbooks (New York: United Bible Societies, 2008), 814. ↩︎

- W. Shaw Caldecott, James Orr, and T. Whitelaw, “Tabernacle,” ed. James Orr et al., The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia (Chicago: The Howard-Severance Company, 1915) ↩︎

- Scott Stripling, “The Israelite Tabernacle at Shiloh”, Academia, Accessed October 12, 2017, https://www.academia.edu/28853265/The_Israelite_Tabernacle_at_Shiloh ↩︎

- Myers, Richard. Logos Bible Images. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2012. ↩︎

- Biblical Archaeologist (American Schools of Oriental Research, 1991). ↩︎

- K.A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 307 ↩︎

- Bible and Spade 16, no. 2 (2003): 43. ↩︎

- Harris, W. Hall, III, Elliot Ritzema, Rick Brannan, Douglas Mangum, John Dunham, Jeffrey A. Reimer, and Micah Wierenga, eds. The Lexham English Bible. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2012. ↩︎

- De Vries, Simon J. 1 and 2 Chronicles. Vol. 11. The Forms of the Old Testament Literature. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989. ↩︎

- Steven Rudd, “Saul Becomes King”, Bible.ca, Accessed November 1, 2017, http://www.bible.ca/archeology/bible-archeology-maps-timeline-chronology-1samuel-eli- samuel-saul-becomes-king-1046-1019bc.htm ↩︎

- BAR, “Israelite Sanctuary at Shiloh?-The Archaeological Evidence”, BAR. Biblical Archaeology Society, 1975. ↩︎

- BAR, “Israelite Sanctuary at Shiloh?-The Archaeological Evidence”, BAR. Biblical Archaeology Society, 1975. ↩︎

- BAR, “Did the Philistines Destroy the Israelite Sanctuary at Shiloh?—The Archaeological Evidence.”, BAR, Biblical Archaeology Review, BAR 1:02 ↩︎

- Stripling, Scott. “Biblical Archaeology: Judges” Class #2, The Bible Seminary, September 29, 2017. ↩︎

- Israel Finkelstein, “Shiloh Yields Some, But Not All, of Its Secrets”, BAR. Biblical Archaeology Society, 1986. ↩︎

- B. Pick, “Seder Olam,” Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1880), 502. ↩︎

- Johnson, Ken, Ancient Seder Olam (Kindle Location 226), Biblefacts.org. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

- Steven Rudd, “The dirty little secret about the Modern Jewish Calendar”, Bible.CA, Accessed November 2, 2017, http://www.bible.ca/manuscripts/Seder-Olam-Rabbah-full-text-PDF-Free-Online-Chronology-modern-Jewish-calendar-Textual-variants-Bible-manuscripts-Old- Testament-Torah-Tanakh-Rabbinical-Judaism-160AD.htm ↩︎