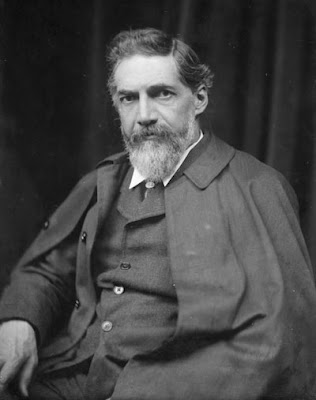

In the history of archaeological research, one man stands out. Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie was as eccentric as he was brilliant. In the late 1800s, archaeological research was in its infancy. Many archaeological expeditions were nothing more than glorified treasure hunts. Petrie was foremost among a growing group of researchers who treated archaeology as a science.

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

Early Life

Petrie was born in 1853. According to his memoirs, he was an archaeologist from birth. Petrie recalled that at the age of eight, he understood the need for archaeologists to carefully peel back the earth in shallow layers rather than shovelling deep holes in search of artifacts. At the same age, he became a coin collector. His prize find was a coin of Emperor Allectus dating to the third century AD.1 As a teenager, Petrie discovered that he could earn money through coin collecting. He would buy large batches of old coins, sort through them, and sell the unique ones to the British Museum.2

Petrie had little formal education as a child. He recounted that formal attempts at learning led to mental breakdowns. When left to his own devices, he devoured books on every subject except Algebra, for which he had to take a remedial course in college.3

Petrie’s father had a background in surveying, and Petrie learned how to survey from him. In his early twenties, Petrie surveyed all the ancient sites he could find in southern England, and drew over 150 site plans.4

The Pyramids

In 1988, at the age of 27, Petrie set off for Egypt. His father had long planned to survey and measure the pyramids, and Petrie was to accompany him. In the end, Petrie traveled to Egypt first. His father planned to join him there, but circumstances prevented him from coming.5

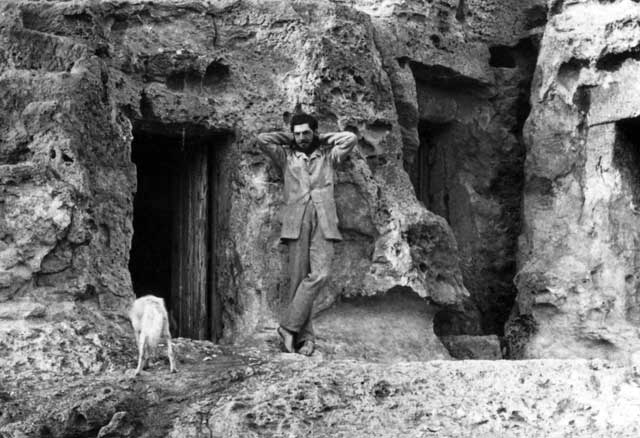

After arriving in Egypt, Petrie settled into a rock-cut tomb, which became his home. He began his work on the pyramids, surveying and measuring them both inside and out. Tourists were an annoyance, and he found that he could only work inside the pyramids at night, after the tourists were gone for the day. During the day, Petrie worked outside the tomb. But, tourists pestered him with questions and delayed his work. He decided that the tourists might leave him alone if they thought him to be weird, so he took to wearing pink clothing. It worked. The tourists left him alone after that.6

Excavations in Egypt

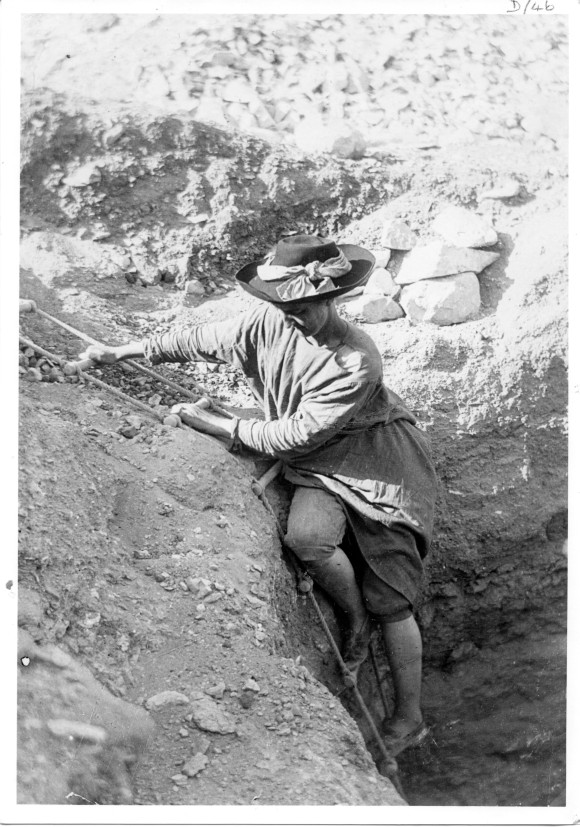

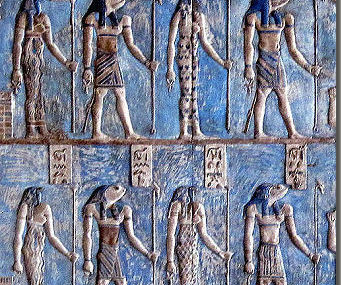

After surveying the pyramids, Petrie went on to conduct several excavations in Egypt. He excavated at Tanis, Tell Nebesheh, Fayum, Amarna, and Luxor. Unlike Petrie’s predecessors and contemporaries who dug as quickly as possible to find as many artifacts as possible, Petrie was slow and methodical. He recognized differences in the style of the pottery and finds. He realized that the differences corresponded to the soil layer from which the artifact came.

Petrie followed the principle of geologists studying rock layers. They understood the layers to represent time. The lower the layer, the older it was. Petrie applied this principle to archaeology, realizing that lower layers of dirt were laid first – the layers on top of them were laid later. He started to build a typology of pottery and artifacts by recording which items were found in which layers. By doing so, he was able to establish the chronological order of the artifacts. Petrie’s typology is still in use to this day.

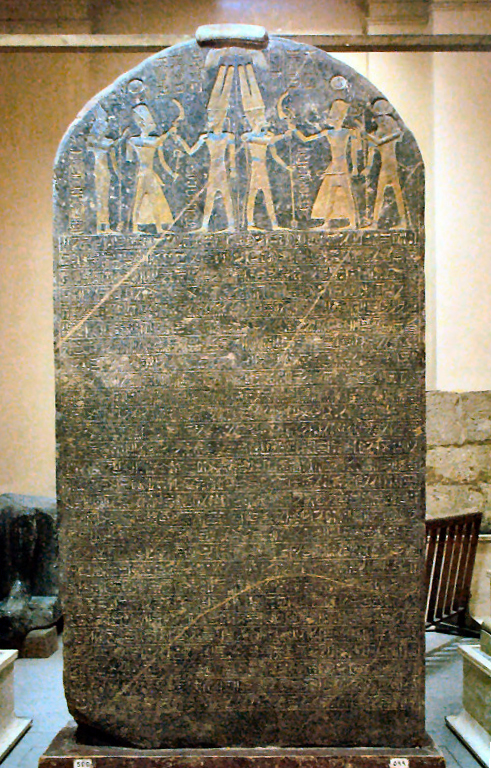

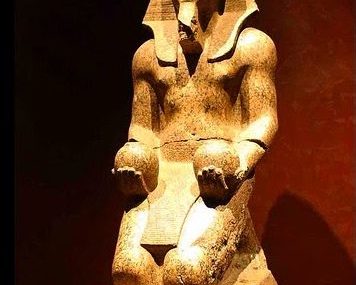

The Merneptah Stele

Although Petrie focused on artifact typology rather than treasure-hunting, his archaeological excavations yielded a number of highly important artifacts. While excavating at Luxor, Petrie found a commemorative stele of Pharaoh Merneptah. This stele stood over 10 feet tall and spoke of Merneptah’s victories over various people groups in the southern Levant including Israel. This was the first mention of Israel ever found in Egypt. It established the fact that Israelites were already living in Canaan at the time of Merneptah in the late 13th century BC. At a dinner party shortly after finding the stele, Petrie predicted, “This stele will be better known in the world than anything else I have found.”7 His prediction came true; to this day, the Merneptah Stele is one of Petrie’s most notable claims to fame.

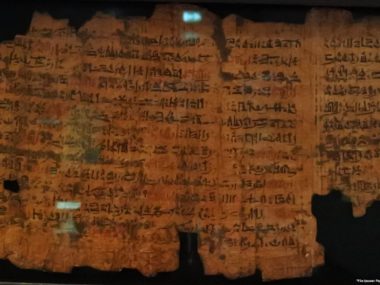

Sinaitic Alphabet

Later, while doing archaeological work in the Sinai Peninsula, Petrie made another important discovery. There, in the turquoise mines, he discovered inscriptions that had some similarities to Egyptian hieroglyphs. But, as he studied them, he realized that they did not follow the Egyptian style of writing, which was a combination of symbols representing words and symbols representing syllabic sounds. Instead, this writing was alphabetic. Petrie had discovered some of the earliest known examples of alphabetic writing in the world. Although Petrie didn’t know it at the time, later discoveries in Canaan would show that this was the alphabet used by both Canaanites and Israelites. Eventually, the Hebrew alphabet developed from this same system of writing.

Excavations in the Holy Land

In 1890, Petrie made his first trip to the land that is modern day Israel. At the time, the region was under Turkish control and was known as Palestine. Petrie’s first excavation in the Holy Land was at Tell el-Hesi, which he mistakenly believed to be biblical Lachish. Petrie’s methodological work at Tell el-Hesi made this the first scientific archaeological excavation in the Holy Land, and he worked to develop a typology of the local pottery.

It wasn’t until 1926 that Petrie began a new project in the Holy Land. He excavated at Tell Jemmeh, which he equated with biblical Gerar. He also excavated a Philistine cemetery at Beth-Pelet and the ancient city of Gaza at Tell el-Ajjul.

Life and Death

In 1891, Petrie received an honorary doctoral degree from Oxford University. He also received a professorship at University College in London.

In 1896, when he was 43 years old, Petrie turned his thoughts to matrimony. He wrote in his memoirs, “Just then a lady came to the exhibition whom I eyed from room to room … sundry talk followed.”8 Later that year, the lady in question, Miss Hilda Urlin, agreed to marry Petrie. They honeymooned in Egypt. Hilda was a trained geologist, and she was particularly skilled at drawing. She put her drawing skills to use in documenting her husband’s archaeological finds. In working with Petrie, Hilda became a skilled archaeologist and Egyptologist in her own right. She directed excavations of her own and worked alongside her husband in his excavations.

In 1933, Petrie retired from his professorship at University College. He and Hilda moved to Jerusalem, where Petrie spent his final years.

Petrie died on July 28, 1942. His body was buried in the Protestant cemetery on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. The Protestant cemetery now lies within the grounds of Jerusalem University College, and Petrie’s tomb is clearly marked. Archaeology students like to visit his grave and leave a potsherd on his headstone to commemorate his contribution to the science of archaeology.

Petrie rightly believed himself to be brilliant. He had an idea that future generations of scientists might like to examine his brain to understand its workings. For that reason, he donated his head to the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Before Petrie was buried, his head was removed and preserved in a jar. Rumors abound about how his head was transported to London and what became of it once it arrived. Most scholars agree that Hilda Petrie did not carry his head to London in a hatbox, despite persistent rumors to that effect.

For some time, the jar with Petrie’s head was lost in the archives of the Royal College of Surgeons. Eventually, it came to light, but was not labeled. In 1989, archaeologist Shimon Gibson was invited to come to London to determine whether the head in the jar actually belonged to Petrie. Gibson was able to positively identify the head based on a scar on the forehead.

Thus, Petrie’s body lies in a tomb in Jerusalem, while his head, in a jar in London, awaits further research.

Summary

Petrie was as brilliant as he was eccentric. His meticulous work in archaeology earned him the title of father of scientific archaeology. He changed archaeology from a treasure hunt to a science. He studied the earth layers at archaeological sites and the artifacts found in each layer. By doing so, he was able to establish a typology that is still used to this day, although now it has grown far beyond what Petrie accomplished in his lifetime. It is now standard archaeological method to excavate slowly, one layer at a time. Archaeologists record the earth layer in which they find each artifact, and they compare the artifact to those from other sites. As each archaeological excavation adds data to the typology, it grows and becomes more firmly established.

References

- Petrie, Flinders. 1932. Seventy Years in Archaeology. Henry Holt and Company, 8. ↩︎

- Petrie 1932, 15. ↩︎

- Petrie 1932, 6–7. ↩︎

- Petrie 1932, 14. ↩︎

- Petrie 1932, 19. ↩︎

- Petrie 1932, 21–22. ↩︎

- Petrie 1932, 172. ↩︎

- Petrie 1932, 175. ↩︎

A wonderful article Abigail. Though I am not an archaeologist, or even involved in any related scientific fields, Petrie is one of my heroes. If I ever make it to Jerusalem one day, I plan to visit his resting place. Thank you for sharing some of Petrie’s greatness & his profound contributions to our knowledge of the ancient world. And I’m glad they finally were able to locate his head.