In 2000, excavators in a clay pit in southern Poland uncovered a treasure trove of fossil bones. Many of them belonged to animals commonly found in other Upper Triassic rocks around the world. They included the heavily-armored, herbivorous aetosaurs and the giant, carnivorous amphibian Metoposaurus. Among the more common Triassic fossils found at the Krasiejów clay pit, paleontologists discovered a new type of dinosaur-like reptile.1 This creature was named Silesaurus (pronounced “SIGH-le-SORE-us”) after the region of Silesia in southern Poland where its fossils were found.

The following is a summary of “Evidence for a Silesaurid (Archosauria: Dinosauriformes) Holobaramin with a Discussion of Triassic Dinosaurs” by J.J. Guzman and Matthew A. McLain, and of the surrounding research pertaining to it. The views expressed are not necessarily those of New Creation.

The Miniature Dragon of Silesia

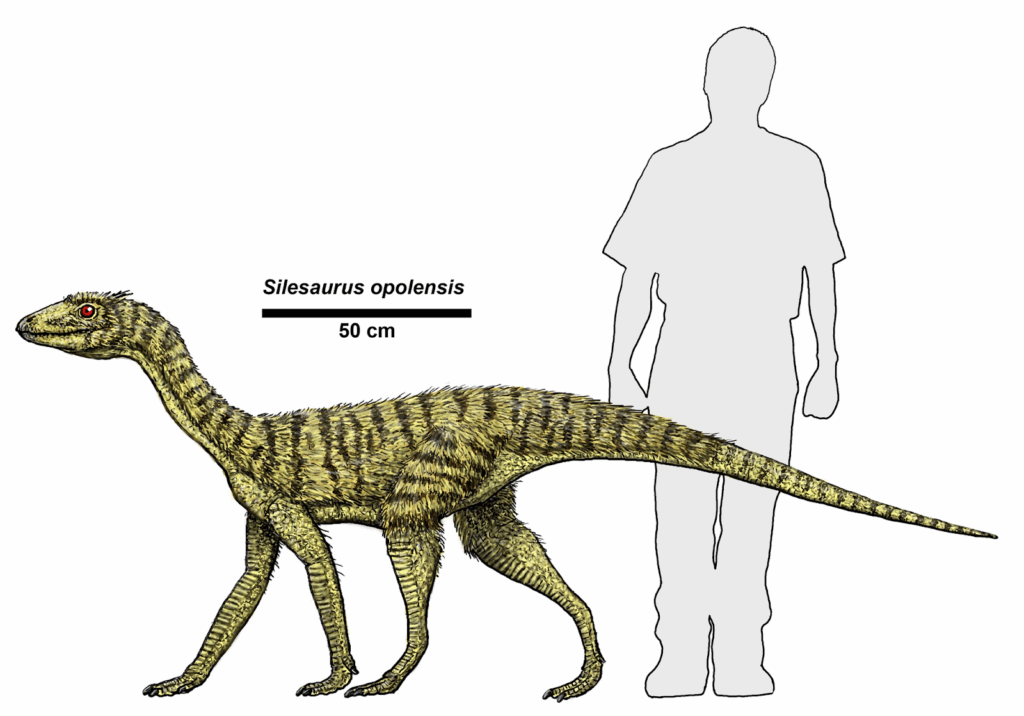

Multiple skeletons showed Silesaurus was lightly built with a long neck and long legs positioned underneath the body.2 It was a medium-sized animal, only about the size of a sheep. The original researchers concluded it was an herbivore based on its cone-shaped teeth and its beak-tipped mandible. However, coprolite (fossil feces) evidence suggests it may have actually eaten insects.3 What was most interesting about Silesaurus was the fact that, while it was dinosaur-like in many ways, it also lacked some important dinosaur traits. It was a biological mosaic, possessing a mixture of both dinosaurian and non-dinosaurian traits.

After the discovery of Silesaurus, researchers identified and classified fossils of similar animals as part of the same family, the Silesauridae. Today, we know of over a dozen silesaurid species. They come from Middle-Upper Triassic rocks in Madagascar, mainland Africa, North and South America, and Europe. Nonetheless, evolutionary paleontologists do not agree on how the silesaurids should be classified. Some have argued that they are actually dinosaurs. Others maintain they are “non-dinosaurian dinosauriforms” (paleo-speak for “shaped like a dinosaur, but not a dinosaur”).

Were Silesaurids a “Created Kind”?

In the first issue of our own New Creation Studies Journal, J.J. Guzman and Matthew McLain present new research on silesaurid baraminology. Baraminology is the scientific study of created kinds. While two previous baraminology papers touch on silesaurids, this is the first baraminology study to focus specifically on silesaurids.

In baraminology, a holobaramin is a group of organisms that shows significant similarities or continuity among members within the group but significant dissimilarities or discontinuity with organisms outside the group. Creation biologists believe that holobaramins are good approximations of what creationists more commonly call “created kinds.” Given what we already know from previous baraminology studies, Guzman and McLain began their research with the hypothesis that the silesaurid family is a holobaramin.

To test their hypothesis, they used a variety of statistical methods to quantify and visualize the overall similarities and differences among the silesaurids and the other animals included in their study. Using different datasets with different combinations of traits and taxa, they found that most silesaurids show continuity with each other and discontinuity with other reptiles. These findings support the existence of a silesaurid holobaramin.

Implications for Dinosaur Evolution

As mentioned above, evolutionary paleontologists are divided over whether silesaurids are dinosaurs or not. Some think silesaurids were the closest relatives to dinosaurs, a twig sprouting off the main limb of the dinosaurian branch in the tree of life. Others believe they reflect an early phase in the evolution of ornithischian (pronounced “or-nith-IS-key-an”) dinosaurs. Ornithischians are more commonly known as “bird-hipped” dinosaurs in contrast with the “lizard-hipped” or saurischian (pronounced “sore-IS-key-an”) dinosaurs. Ornithischians are common in Jurassic and Cretaceous rocks and include many famous dinosaurs like Triceratops, Pachycephalosaurus, and Parasaurolophus.

Representatives of the two groups of saurischian dinosaurs—the sauropodomorphs (the long-necked dinosaurs) and theropods (carnivorous, bipedal dinosaurs)—are known from Triassic rocks, the lowest of the dinosaur-bearing layers. Since evolutionists believe all dinosaurs had a common ancestor, they think ancestral ornithischians must have also lived during the Triassic Period. But since paleontologists haven’t found convincing fossils of Triassic ornithischians, some have wondered if silesaurids might be the missing ancestral ornithischians.

Guzman and McLain’s new paper has important implications for these theories about dinosaur evolution. If silesaurids were truly dinosaurs’ closest cousins, we might expect them to show continuity with some of the “early” dinosaurs in the dataset. By and large, this isn’t what they found. If silesaurids represented an early phase in ornithischian evolution, we might expect them to show strong continuity with “early” ornithischians. By and large, they didn’t find this either. Instead, silesaurids appear to be discontinuous with dinosaurs and other reptiles. Likewise, so-called “early” theropods and sauropodomorphs do not have continuity with each other.

In conclusion, Guzman and McLain’s overall findings fail to support evolutionary ideas about the origins of the major dinosaur groups. They do, however, provide support for the identification of a silesaurid holobaramin. To find out more about dinosaur origins, read Christian Ryan’s article “Where Did Dinosaurs Come From?”

Footnotes

- Dzik, J., & Sulej, T. (2007). A review of the early Late Triassic Krasiejów biota from Silesia, Poland. Palaeontologia Polonica, 64, 3-27. ↩︎

- Dzik, J. (2003). A beaked herbivorous archosaur with dinosaur affinities from the early Late Triassic of Poland. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 23(3), 556-574. doi:10.1671/A1097 ↩︎

- Qvarnström, M., Wernström, J. V., Piechowski, R., Tałanda, M., Ahlberg, P. E., & Niedźwiedzki, G. (2019). Beetle-bearing coprolites possibly reveal the diet of a Late Triassic dinosauriform. Royal Society Open Science, 6(3), 181042. doi:10.1098/rsos.181042 ↩︎

Dinosaur-like, but not dinosaurs. Similar things could be said of a lot of cases, I reckon. Birds are lumped in with dinosaurs because various “dinosaurs” have features found in birds, but we know some dinosaurs weren’t like birds at all. A lot depends on subjective or arbitrary standards involving rather small and/or subtle features, while ignoring great differences in key features. When you look at all the cases that even evolutionists attribute to “convergence” or “parallel evolution” instead of common ancestry, it’s easy to be skeptical of the big story of universal common ancestry.

I know you’re trying to summarize, but at least give us some examples of discontinuity and why they are not a dinosaur. I found myself asking a lot of “like what?” Or “why?” I would’ve read a little longer article that gave me more information.

Thank you for your honest feedback! This particular article was meant to be a short summary of the paper in New Creation Studies, so we wanted to keep its length down. Nevertheless, I will keep your feedback in mind for future articles.

One example of a difference between silesaurids and dinosaurs is the presence of a closed acetabulum (the anatomical term for the hip socket) instead of an open acetabulum. An open acetabulum is typically considered a defining character of Dinosauria. Hence, it’s absence has led many researchers to conclude they are not dinosaurs.