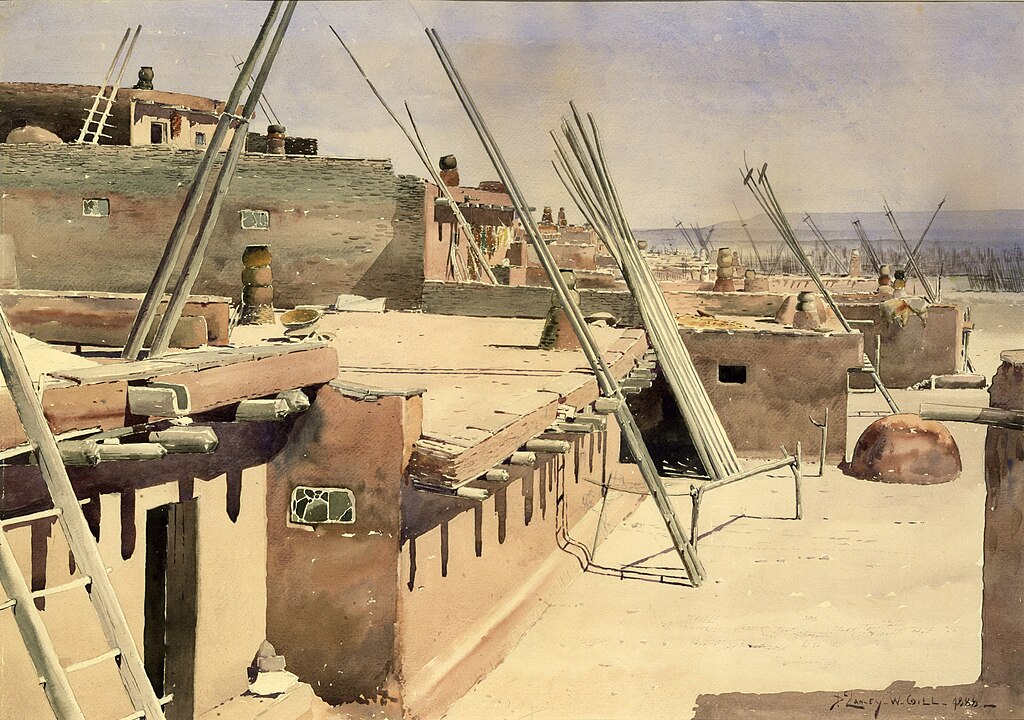

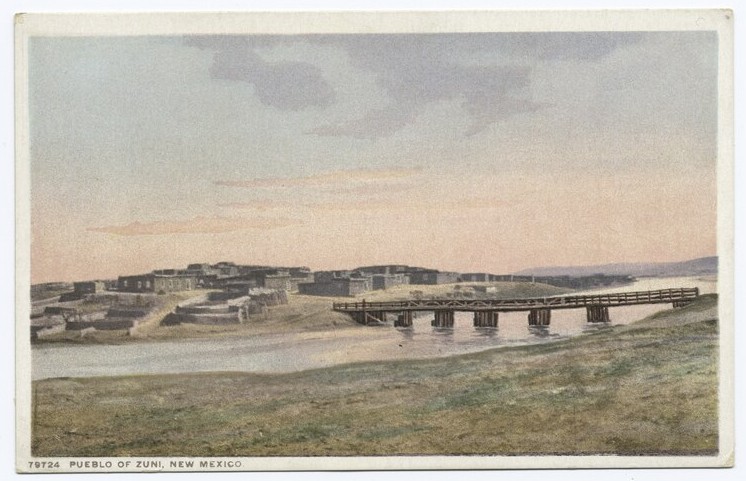

Last year, I had the opportunity to listen to the retelling of a Native American flood legend. I spent six weeks in New Mexico over the summer, participating in an archaeological dig. On the way home, my group stopped by the Pueblo of Zuni. We planned to tour the Zuni museum and meet with one of the elders. We parked across the street at a shop and walked over to the museum. It was housed in a somewhat dilapidated building. The adobe façade was chipped and stained in places. The teal paint of the sheet metal overhanging the porch was peeling. A stray dog trotted along with the group, emitting low yips and howls. Our group tramped up the stairs, onto the porch, and to the door. We were greeted by a young native woman with tanned skin and straight black hair. She welcomed us in and introduced us to the museum director.

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author mentioned, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

After viewing the exhibits, we stepped down into the director’s office. The space was filled with folding chairs. Roughly thirty people crammed into the room, facing a large television screen. The director sat behind us at a large desk. Near the television, sat an elderly Native American gentleman. He led one of the Pueblo’s seven kivas, or places of native worship. The old man was blind but had a radiant smile. He constantly grinned towards the voices of the unseen visitors. Once everyone quieted down, he asked what we would like to know about the Zuni. I spoke up: “Could you tell us the story of the Flood?” The elder’s smile widened, and he began the legend in a slow, mellow voice. I have paraphrased the story below, adding a few additional details for context.

The Zuni Flood Legend

Long ago, the Zuni people lived in this valley. They built a pueblo and grew corn in their fields.

The elder paused, and for the first time, his face bore a frown. Haltingly, he said that the Zuni had done bad things but did not elaborate. Later, upon reading published reports of Zuni mythology, I learned that the Flood was caused by incest. Members of the Corn Clan lay with each other, angering the spirit of an ancestor.

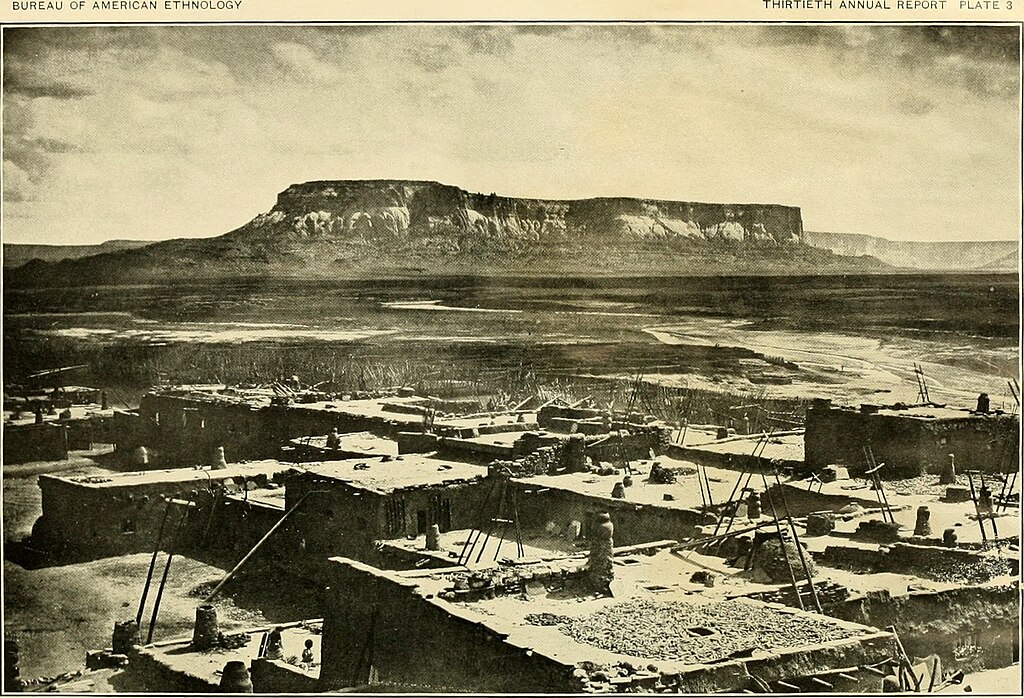

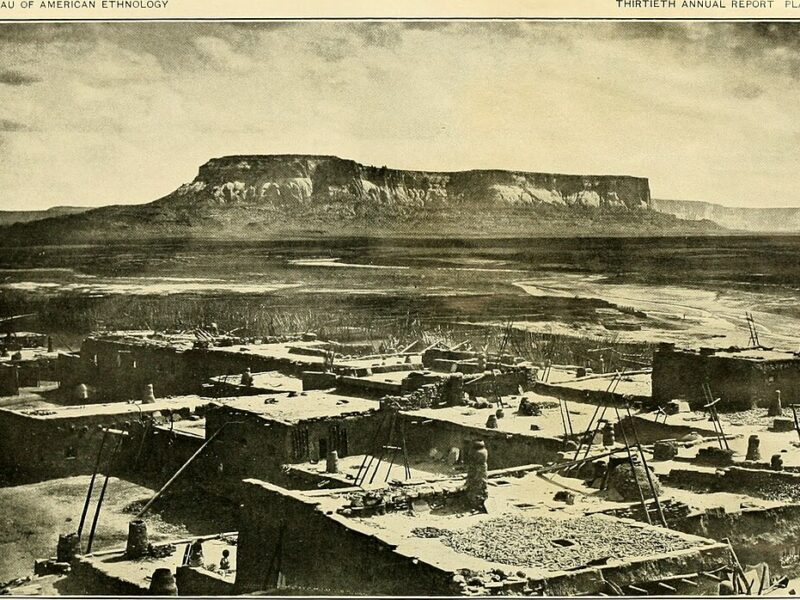

Then, it began to rain. The rain poured down, and soon the valley began to flood. The people abandoned their pueblos and fled to high ground. They climbed up to the top of Corn Mountain, a large mesa to the southeast. The waters rose, and soon the mesa was an island, surrounded by water. The people could see the great water serpent, Kolowisi, circling the mesa.

In some versions of the story, Kolowisi is said to have held back the floodwaters long enough for the people to reach the mesa. He is also credited with providing food for the people while they were stranded on the mesa top. But my storyteller did not mention these details.

Even the mesa top was not safe. The water was rising so quickly that within a few days it would be submerged. The elders met together to discuss what they could do to stop the flood. They decided that they must offer some sort of sacrifice. But the elders could not agree on what to offer. Every man returned to his family that night to think over the problem. The next day, the elders met again. One man suggested that they must sacrifice two children. The elders agreed, but no one wanted to give up their children. The next day, the elders met again. This time, it was decided that their leader should offer his children.

The leader had only two children, a boy and a girl. When he returned home that night, he asked his children to give themselves up for the survival of the tribe. The children freely chose to be sacrificed. They knew that they would die anyway if the floodwater rose further. So, the next day, the two children dressed in ceremonial clothes. They each carried a basket of food offerings and held incense sticks. In the sight of the elders, the boy and the girl walked to the edge of the mesa. At this point, the waves were high and foamy. The mesa top was only just above water. The children stepped into the water and slowly walked down the slope. First, the water covered their legs, then their body, and soon their heads were submerged.

The sacrifice was appeasing, and the rain stopped. The floodwaters began to drop. At their zenith, the foaming waves had discolored the rock, leaving a white ring of stone around the mesa. Once the water dropped further, the people saw two pillars of rock where the boy and girl had descended. The children had turned to stone pinnacles, commemorating their sacrifice. Finally, the floodwaters abated, and the Zuni people were able to return to the valley and rebuild their pueblo.

A smile finally crept across the elder’s face again. He told us that the Zuni still consider the mesa to be sacred. Pregnant mothers travel up the side of the mesa to the twin pillars. If she wants to have a girl, she prays and plants an incense stick in the soil at the base of the girl’s pinnacle. If the mother wants a male child, she does the same at the boy’s pillar.

Evidence of a Global Flood?

Before visiting the Pueblo of Zuni, I had read a few tribal flood legends. Sitting next to a native elder telling the story was a completely different experience. His slow, methodical speech revealed the drama of the simple story. Chills passed up my spine when I imagined the great sea serpent circling the mesa. Was this a distant memory of the global Flood?

The Bible and the Zuni flood legend attribute the Flood to a similar cause. The Zuni believe that the Flood was a judgment for sexual misconduct. Young people of the same clan had sex with each other without regard for how closely they were related. Indiscriminate sexual relationships are also discussed in the Bible. Genesis 6:2 (ESV) describes how Seth’s lineage was corrupted: “the sons of God saw that the daughters of man were attractive. And they took as their wives any they chose.” What a striking similarity between the stories!

However, there are also major points of difference between the Zuni legend and the Bible. The Zuni story is beautifully blended into the local geography. Living in the desert, there is little use for a boat. The ark’s protection was discarded in favor of the huge mesa. The Zuni story also incorporates sacrifice in a manner different from the biblical text. They believe that human sacrifice was necessary to appease the spirits. In the Biblical story, Noah sacrificed clean animals after the Flood to thank God for his deliverance. But in any case, the Zuni legend does contain striking thematic similarities to the Biblical story.

Concluding Thoughts

My skeptical side questions whether this legend could be better interpreted as describing a local flood. The Pueblo of Zuni is located in a river valley. In fact, the Zuni River runs directly through the center of the Pueblo. Could the Zuni legend be an embellishment of a historical flood? The Zuni River may have overran its banks in ancient times, flooding the Pueblo. It seems possible that the Zuni Flood legend is an embellishment of a local flood. In this context, the Zuni’s relocation to the mesa top could be taken literally. Perhaps the river valley flooded, forcing the Zuni to seek the high ground of the nearby mesa. Ruined pueblos sit atop the mesa, indicating that it was once occupied. The story leaves me unsatisfied. I might consider the legend more persuasive evidence of a global Flood if the Pueblo were not located on a riverbank.

Tribal flood legends often contain interesting parallels to the biblical Flood story. However, it is important to approach these legends skeptically. Some stories may be embellished accounts of local floods, while others may be Christianized myths. It is unclear whether stories like the Zuni flood legend originated from the biblical Flood. But the sheer number of tribal flood legends does support a common origin. The best cultural evidence for the flood comes from Mesopotamian flood legends. These tales contain many of the same elements as the biblical story. They suggest that Mesopotamian peoples possessed a true cultural remembrance of the biblical Flood.

Footnotes:

Benedict, R. (1935). Zuni mythology [as cited in The Great Flood]. (n.d.). In Native-Languages.org. Retrieved August 29, 2025, from https://www.native-languages.org/zunistory.htm

Kolowisi. (n.d.). Keshi: The Zuni Connection. Retrieved August 29, 2025, from https://keshi.com/pages/kolowisi

This was a really good article. I had never heard this flood myth before, and it was very interesting.