Trees usually fall over and rot when they die. It makes sense, then, that we find most fossil trees lying on their sides. Fossil Grove in Glasgow is quite unique, because it features nearly a dozen tree stumps standing upright! According to conventional wisdom, this is a remnant of the forest that grew in place before its burial and preservation. But a recent study of the site suggests an alternative, more catastrophic scenario might be at play.

The following article is a summary of the research pertaining to “Fossil Grove and other Paleozoic Forests as Allochthonous Flood Deposits” by Kurt Wise. The views expressed reflect those of the authors mentioned, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

What is Fossil Grove?

Located in Glasgow, Scotland’s Victoria Park, lies one of the world’s finest preserved examples of a fossilized forest: Fossil Grove. It was discovered in 1887 when construction was underway for the extension of the park. Workers were in for a surprise. They discovered the fossilized stumps of eleven trees preserved in a 35-inch thick layer of gray-colored sandstone. The stumps varied in height from 4.2 inches to 19.2 inches. And they varied in diameter from 13 to 39 inches in diameter. To protect this incredible find from the elements, they constructed a building over the site. This building served, too, to display these time capsules from the past for public viewing and scientific research.

The Trees That Aren’t Trees

Technically, these “tree stumps” are not tree stumps at all. They are actually sandstone casts. These formed when sand filled the once hollow tree stumps. The plant itself rotted away, leaving behind the casts we see today. We should note that the term “tree” is not scientific jargon, but a folk taxonomic term. We often use folk taxonomy to categorize plants that are similar in general appearance, even if such similarities are superficial. As such, the trees of Fossil Grove only look like the tall, leafy plants growing outside. They are technically called lycopods. This is a group of ancient plants similar to modern quillworts, but often growing much larger in size.

The particular lycopods preserved at Fossil Grove, researchers believe, are of the genus Lepidodendron. When full grown, these massive plants could get six feet wide and tower over 130 feet above the ground. Lycopods are known for having a unique root system that horizontally radiates out from the tree itself. Each root resembles a bottle brush or a pipe cleaner, covered in tiny roots called “rootlets.”

Did the Fossil Grove Lycopods Grow in Place?

Autochthonous vs. Allochthonous

The term “fossil forest” may convey a forest that simply grew and was buried in place. Paleontologists, however, recognize two main types of “forests” in the fossil record. These are allochthonous forests and autochthonous forests. An autochthonous forest consists of fossilized trees buried in the same place and position in which they grew. Whereas an allochthonous forest consists of fossilized trees dislodged, transported, and buried somewhere other than where they grew.

A famous allochthonous forest formed after the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980.1 A forest of more than 154 square miles of trees washed into the nearby Spirit Lake, creating a floating mat of logs and stumps more than two square miles. While the log mat is still there today, it has decreased in size. In part, because some logs have washed up on the shore. Many other logs, however, became waterlogged. They sank bottom-first, landing rightside up on the lake floor, dragged down by the heavier weight of the trees’ root systems. Researchers estimate 60% of the once-floating plants (about 19,500 erect stumps and 12,000 logs) have planted themselves on the bottom of the lake. The exact number will change as some fall over and new ones sink. The bottom of Spirit Lake resembles a submerged forest, despite the fact that none of these trees grew in place.

What About Fossil Grove?

Young-earth geologists express disagreement over which type of fossil forest Fossil Grove represents. This may relate to the fact that even conventional geological literature has published surprisingly little detailed research on Fossil Grove. Regarding fossil forests in general, though, young-earth geologists most widely accept the model of the allochthonous explanation. Based on this understanding, the lycopods at Fossil Grove grew elsewhere, became dislodged from their growing place, and water transported them. Sometime later, they became waterlogged and sank to the bottom. There, a thick layer of sediment preserved them, similar to the fossil forest in Spirit Lake.

This contrasts with the conventional explanation for Fossil Grove. Old-earth geologists, as well as some young-earth geologists, think that the stumps preserved at Fossil Grove were part of a low-lying swamp forest. This forest centered along large rivers that flowed through raised channels. Sometimes, the rivers would flood and overflow into the surrounding landscape. These floods would knock over and kill trees. Sand and mud would deposit around the tree stumps that remained. Overtime, the stumps hollowed out as they rotted, leaving only the outer bark. More flooding washed sediment in, filling the hollow stumps with sand, before completely burying and hiding them from view. 2,3

Dr. Kurt Wise, a young-earth paleontologist, did not agree that Fossil Grove was an autochthonous fossil forest. So, he traveled to Fossil Grove in Scotland to make his own observations of the site. His research on Fossil Grove appeared in the Answers Research Journal in 2018.4

Looking for Clues

In order to determine whether Fossil Grove is an autochthonous forest or allochthonous forest, we must first have an understanding of its context within the geologic record overall. Researchers currently think the sedimentary rocks preserved here belong to a sequence of layers called the Limestone Coal Formation. They occur beneath more than a mile of the Glasgow region’s coal-bearing sediments. With this in mind, let us look at the observations Dr. Wise made at the Fossil Grove site.

Stumped on Fossils

As stated before, Fossil Grove preserves a total of 11 tree stumps on site. Nine of them have attached root systems. One stump is preserved without its roots. There is one root system missing the rest of the stump. Root systems radiated outward up to six feet from the trunks.

Tree stumps are not the only fossils preserved at Fossil Grove, however. There is an entire salad of unattached, sand-filled root fragments, compressed fossils of the extinct plant Cyperities, and eight or so logs or branches oriented in a northeast-southwest direction. While most of the logs/branches remain unidentified, researchers believe at least four of them belong to the genus Lepidodendron, just like the stumps. Scientists have also reported preserved burrows of Arenicola, a type of marine worm.

One Layer At a Time

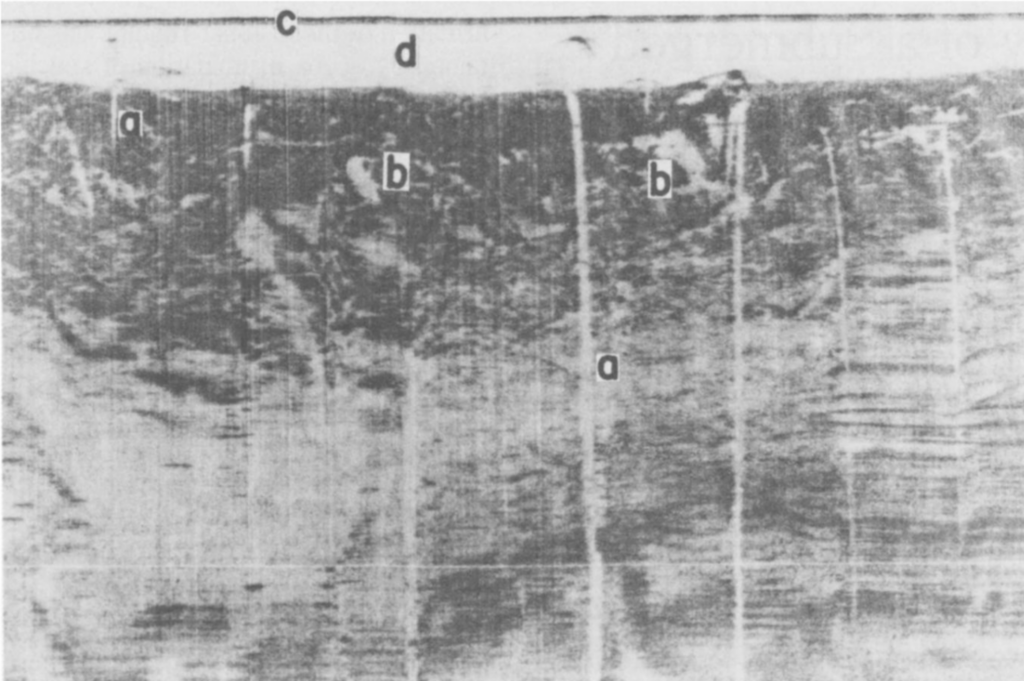

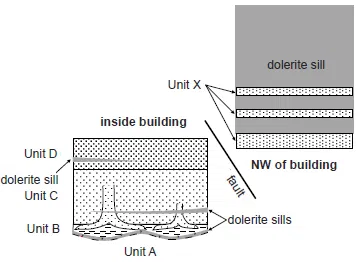

Fossil Grove is primarily composed of silty shale and sandstone. From his own investigation of the site, Dr. Wise has divided the rock layers into five main units. From top/youngest to bottom/oldest, he has labeled these Units A, B, C, D, & X. All but one can be found inside the Fossil Grove building itself. To view Unit X, you must journey outside of the building.

Unit D

Composed of coarse, thinly-layered siltstone, Unit D is cross-bedded. This means that inclined or tilted layers of sediment make up this unit.

Unit C

Unit C is 35 inches of fine- to medium-grained, gray sandstone. It contains most of the fossils found in Fossil Grove, including the tree trunks. The sediment grains of this unit progressively get smaller from the bottom to the top of the unit. It contains eight-inch thick, ripple marked layers. The ripple marks are slightly asymmetrical, suggesting that the current flowed to the southwest as Unit C was formed.

Even though we see the tree trunks are present in Unit C, we find the bases of the stumps actually rooted in Unit B. The tree stumps simply penetrate upward from Unit B and into the sandstone of Unit C. As mentioned earlier, all tree stumps are of different heights. None of them are taller than the top of Unit C.

During the excavation of the site, in order to expose the tree trunks for viewing, excavators removed much of Unit C. All that remains of this unit today are the casts of the tree stumps themselves. But before the excavations took place, Unit C was once an extensive rock layer that was continuous with the sandstone that currently infills each tree stump and root system.

Unit B

The lowest of the three units exposed in the Fossil Grove building is Unit B. This unit is composed of irregularly and thinly-layered, dark gray, silty mudstone. It also contains many plant fossils, including fragments and impressions of plant remains (some of which have become coal) and the root systems of the tree trunks that protrude into Unit C. Interestingly, the bottom surface of Unit B is wavy, characterized by smooth, symmetric, and curved undulates. These undulations have a wavelength of about 12 feet and an amplitude of one foot or so.

Unit A

Unlike the other units inside the Fossil Grove building, Unit A is not exposed at Fossil Grove. It can technically be accessed by removing Unit B from on top of it. But seeing as this would destroy Unit B and the plant fossils in the process, researchers choose to infer the nature of Unit A from the bottom surface of Unit B. Therefore, since Unit B smoothly undulates, it is most likely that Unit A does as well.

Unit X

One cannot actually see Unit X inside of the Fossil Grove museum, but you can observe it to the northwest of the building. It is composed of several sandstone layers, most of which show medium- to thick-cross bedding of 1.5 to 3 feet in thickness, though some are smaller. Some researchers have suggested the presence of a river channel in one sandstone of Unit X. However, Dr. Wise does not think this interpretation is correct. When river channels form, they must erode or cut through the pre-existing, underlying layers of sediment. This “river channel” does not do this. Instead, the sides of the channel appear to be bounding surfaces of steeply-dipping sandstone layers that gradually thicken as they rise upward. Instead of a river channel, Dr. Wise suggests that this feature might actually be a 3 or more foot-thick layer of sandstone composed of very steep cross-beds.

We cannot place Unit X directly in context with the other units because it is only visible outside of the museum. However, Dr. Wise suggests that it correlates at or above Unit D because there are substantial similarities between the two.

Fossil Grove Dolerite

Another important feature of the Fossil Grove site is the presence of dolerite. This is a type of fine-grained igneous rock, typically formed through the cooling and hardening of magma within the earth’s crust (as opposed to erupting on the earth’s surface). Commonly associated with intrusions, dolerites occur where magma has intruded into pre-existing rock formations before turning into solid rock.

The dolerites of Fossil Grove are sills. This means they formed when magma intruded sideways into fractures in the pre-existing rock before hardening as a horizontal sheet. Dolerite sills occur at many different levels within this deposit, but radiometric dating firmly assigns them to Lower Permian in age. As creationists, we do not think radiometric dating of rocks this old reflect the actual passage of time that has elapsed. This dating is still important, however, for establishing the relative order of events. In this case, since Fossil Grove is a Carboniferous formation, we know that the dolerite sills were created here afterward because they date to the Permian. This will be an important clue later.

What Do the Clues Mean?

With his observations made, Dr. Wise’s next task was to try and figure out what they all mean. Geologists must learn to read rocks like a historian learns to read ancient texts. The puzzle pieces left behind in the earth’s geologic record can be put back together to reconstruct a story of how they might have formed.

Cross-Bedding

Several of the Fossil Grove units described above contain cross-bedded sediment. Inclined or tilted layers characterize this sedimentary structure within a larger sedimentary deposit. These usually form when wind or, as in this case, flowing water deposit sediment in an inclined or migrating manner. There is no evidence that Fossil Grove is a desert deposit. Dr. Wise can therefore conclude these cross-beds must have formed under conditions of a substantial current, perhaps as underwater dune or sandwave deposits.

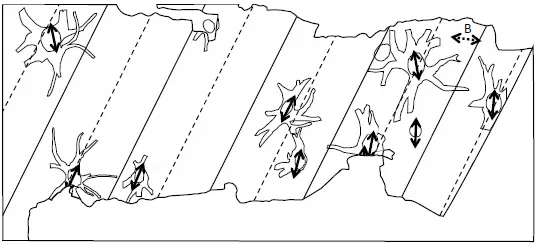

Megaripples

While we cannot observe Unit A directly without disturbing Unit B, we can infer its undulating character from the base of Unit B. Dr. Wise interprets these undulations as large, parallel ripple marks. However, based on their immense size, it may be more appropriate to call them “megaripples.” The orientation of these megaripples indicates a powerful current moved northwest to southeast at the time of Unit A’s formation. The megaripple similarities Unit A shares with Unit B suggests that bidirectional currents emplaced both. In fact, Dr. Wise considers the possibility that Units A and B are not separate units at all, but lower and upper layers from the same depositional event.

The Power of Ancient Currents

It is worth noting that a dolerite sill separates Unit A from Unit B. In fact, most of Fossil Grove’s floor in between the tree stumps is actually a dolerite surface. Is it possible that a dolerite sill itself caused these undulations, and Unit A contains no megaripples at all? Dr. Wise finds this idea inconsistent with the evidence at the site. Perhaps the most significant problem with this is that the dolerite sill penetrates through Unit B, which sits atop of it. This means that the sill did not alter or destroy the original character of Unit B. Therefore the megaripple interpretation still fits best here.

Dr. Wise suggests that, based on the incredible power bidirectional currents would need to form megaripples of this size, Unit A and Unit B may reflect a tsunami or tsunami-like deposit.

Preserved Paleosols? Preposterous!

Paleosols are soil layers (not sediment) preserved within the geologic record, and they are often alleged to be associated with Fossil Grove and other fossilized forests. In particular, old-earth geologists and a number of young-earth geologists have interpreted Unit B as a paleosol. After all, the bases of Fossil Grove’s tree stumps reside within Unit B. However, Dr. Wise identified several observations that are inconsistent with this interpretation.

No Evidence for Soil Development

One of the most glaring inconsistencies is that there are no published reports of evidence for soil development in Unit B. Geologists have merely assumed the presence of a paleosol because these trees “obviously” grew in place. Yet, the development of soil would have altered Unit B after its emplacement, which is not apparent. In the mid-20th century, some researchers suggested that perhaps the original soil washed away prior to the emplacement of the sediment that buried and killed the trees.5 While they give no rationale for this claim, it suggests they either saw no evidence for soil development in Unit B and/or realized that the thickness of Unit B was not deep enough for it to be the rooting soil for the tree stumps.

Insufficient Thickness

Another problem is that Unit B is only a few inches thick. This is not deep enough to have served as the original soil for the Fossil Grove tree stumps. At most, the original soil cover would not have even been thick enough to cover the root systems near the trunk. This is especially problematic considering that, in life, rootlets also covered each root. Currently, there are rootlet scars on all sides of the roots, showing us where rootlets once attached. Fossil rootlets commonly range from inches to multiple feet long. This demonstrates that the existing sediments of Unit B are by no means thick enough to have been the soil in which the stumps were rooted.

There is simply no evidence to support the interpretation of Unit B as a paleosol. It is merely an assumption because researchers assumed the trees themselves grew there. Rather, a better explanation is that what is now Fossil Grove is simply where the waterlogged stumps came to rest atop forming deposits of sandy mud.

No Bioturbation

The fact that the layering of Units B through D (and presumably A) is unaltered from when it was emplaced suggests that they were not subject to bioturbation. Bioturbation refers to the activities of organisms that rework or modify the sediment or soil through various processes. Worms, for example, burrow, feed, crawl, and cause other forms of such disturbance. It is an important component of thriving forest ecosystems today, playing an essential role in recycling nutrients.

Interestingly, geologists cannot attribute the almost complete lack of bioturbation to a lack of living organisms. As mentioned before, researchers have found fossilized worm burrows in Fossil Grove. This tells us definitively that worms inhabited this region while the sediments formed, but they did not extensively bioturbate the sediment.

Dr. Wise suggests that this is because they did not have enough time to do so. The lack of bioturbation implies little to no time elapsed between the formation of Units A and B, B and C, or C and D . The emplacement of the Fossil Grove stumps seems to have occurred very soon after Unit A formed, and only shortly before Unit C filled them and covered them up. Given the immense size of full-grown lycopods, they likely would have taken many years to reach adulthood. However, they do not appear to have grown in the place where they now rest.

Watery Rocks

As discussed before, there are numerous dolerite sills cut through the sedimentary rocks and fossilized stumps at the Fossil Grove site. As is typical for sills, these formed as molten magma was injected sideways into cracks within already existing rock. It then cooled and solidified into flat, horizontal layers. Oddly, the surroudning sediments at Fossil Grove show little evidence of heat damage from contact with the magma.

This is an unusual observation. Typically, a magma intrusion “bakes” the adjacent rock, leading to contact metamorphism. Evidence for this can be seen in the form of recrystallized minerals, alterations to color and composition, and fossil distortion. But at Fossil Grove, evidence for such thermal alteration is surprisingly minimal. Instead, what we do see are chilled margins on dolerite sills (fine-grained edges that indicate the magma cooled quickly upon contact). Meanwhile, the Unit B mudstones and Unit C sandstones show little to no signs of baking, and the site’s delicate fossil structures remain remarkably well preserved.

To make sense of this, Dr. Wise proposes an alternative explanation. At the time of the intrusion, the Fossil Grove sediments must have been saturated with water. Water has a high heat capacity and can effectively absorb and transport thermal energy in porous, unconsolidated material. This implies that the sediments had not yet hardened into rock. Rather, they were still waterlogged and and porous. As a result, they were able to dissipate the heat from the magma quickly, preventing significant heat alteration and preserving the fossils and sedimentary structures.

This seems remarkable considering geologists allege the dolerite sills to be some 35 million years older than the Fossil Grove sediments. Such an observation only makes sense if the sediments were rapidly deposited into water and remained waterlogged at the time of the intrusion.

How Long Does It Take for a Tree Stump to Rot?

As stated earlier, the Fossil Grove stumps and root systems are internal sand molds, not the original plant material themselves. This suggests that the lycopods once growing from them experienced considerable decay a good while before their burial.

While one might suppose that a forest would have time to rot after its destruction, but before its burial, this should be accompanied by some evidence of the forest recovering. Once again, such evidence eludes Fossil Grove, as the sediments remain largely unaltered from the time of their emplacement.

The time required for the Fossil Grove tree stumps to hollow out from rotting suggests that they must have done so elsewhere, and not where their final resting place is located.

How Did Fossil Grove Form?

After studying the site and carefully interpreting the clues, Dr. Wise was able to develop a model of how Fossil Grove may have formed.

He thinks that a very high energy current flow (possibly from a tsunami or tsunami-like surge) moved in a northwest-southeast direction. This formed the megaripples along the surface of what would become Unit A. As the energy from the watery surge lessened, its load began to accumulate atop Unit A. As the water laid down Unit B’s silty muds, it deposited all eleven stumps and a number of the logs here as well. The stumps must have spent a considerable amount of time decomposing, likely while floating in water, before becoming sufficiently waterlogged to sink and settle in their final resting place. Following this, a current from the northeast brought great quantities of sand. This sand not only filled the hollowed out stumps, but buried them as well. This same current also introduced hollow trunks and root systems, forming additional ripple marks on the surface of the water bottom.

Dr. Wise’s model is able to explain the main lines of evidence preserved at Fossil Grove:

- Megaripples, which may only be consistent with large-scale tsunamis

- Tree stump decomposition, which may only be consistent with long float times afforded by a months-long cataclysm

- Thick and rapidly deposited sedimentary formations, which seem only consistent with catastrophism of unparalleled extent

- Rapid transport of magma heat, which may only be consistent with water transport on the scale of a regional to intercontinental scale flooding event

Whatever caused the creation of Fossil Grove must have been a catastrophe on a scale not seen in the present day.

What About Other Fossil Forests?

Where Fossil Forests Are Found—and Why It Matters

Fossil forests, whether allochthonous or autochthonous, occur throughout the geologic column. But their distribution is not random. One study found that researchers report fossil forests far more often within the upper half of the Carboniferous strata than anywhere else in the geologic record.6 This study documents 63 fossil forests in the Carboniferous alone, and four more from the Lower Permian. They occur all across Europe and eastern North America, with Joggins Fossil Cliffs in Nova Scotia and the Blue Creek coal in Alabama being two of many prominent examples.7 46 of these forests specifically contain upright lycopod trees. Dr. Wise suggests that the tendency for lycopods to float upright in water might not only explain most reports of fossil forests, but also explain why so many of them formed in the upper Carboniferous.

How Were Fossil Forests Preserved?

The aforementioned study does not determine whether or not all of these fossil forests could have been allochthonous. However, its authors suggest that the burial of all fossil forests occurred rapidly, and that sediment quickly accumulates on top of them, otherwise erosion would destroy them. This is consistent with the prolonged, rapid burial evidenced at Fossil Grove.

Another similarity is that 40 of the fossil forests reported in the study tend to contain trees from only one type (as seen in Fossil Grove), rather than many different types of trees. This implies that these trees were not part of a regular forest. Of particular interest is the fact that 61 of the fossil forests identified are preserved as internal molds of hollowed trees. This means that nearly all of the fossil forests in this study experienced a long enough period of time for substantial rotting to take place before their rapid burial.

With such a long period of time between death and burial, it is unlikely that the trees’ simply occurred where they grew. A common state of decomposition shared by all of these fossil forests in the same part of the geologic column all over the world suggests a common cause.

When Did Fossil Grove Form?

Dr. Wise believes that the scale, rapidity, and catastrophism of Fossil Grove and other fossil forests is consistent with the global Flood as described in the Book of Genesis. If this understanding is correct, we can hypothesize.

While not discussed in length in this article, Dr. Wise thinks the lycopods made up a buoyant, floating forest that existed on the ocean’s surface before the Flood. They would have been dislodged from their original growing location early during the Flood year. The lycopods were sent drifting on the ocean. The currents would have swept the logs into large mats, as seen in Spirit Lake today. The floodwaters continued to rise as months passed. During this time, the logs rotted until they became hollow husks of their former selves. Eventually, the trunks became waterlogged. They sank to the bottom in upright clusters at many locations around the northern hemisphere at the same time.

Conclusion

While Fossil Grove has been celebrated as an incredible fossil discovery, actual published research on it has been rather meager. Before the publication of Dr. Wise’s work on the site, only a handful of academic, technical papers have spilled ink on these mysterious lycopod trunks.

Dr. Wise was only able to examine the site for a brief time and under extremely poor light conditions. Nevertheless, his work is a welcome addition to Fossil Grove literature. He suggests that further study of this site will expose evidence that will only make sense within a young-earth timescale.

Footnotes

- Coffin, H. G. (1987). “Sonar and scuba survey of a submerged allochthonous ‘forest’ in Spirit Lake, Washington.” Palaios, 178-180. ↩︎

- Allison, Ian, and David Webster. 2017. A Geological Guide to the Fossil Grove, Glasgow. Glasgow: Geological Society of Glasgow. ↩︎

- Clarey, Timothy L., and Jeffrey P. Tomkins 2016. “An Investigation into an In Situ Lycopod Forest Site and Structural Anatomy Invalidates the Floating-Forest Hypothesis.” Creation Research Society Quarterly 53 (Fall): 110–122. ↩︎

- Wise, K. P. (2018). “Fossil Grove and other Paleozoic Forests as Allochthonous Flood Deposits.” Answers Research Journal, 11, 237–256. ↩︎

- MacGregor, Murray and John Walton. 1948. The Story of the Fossil Grove. Glasgow, United Kingdom: City of Glasgow Public Parks and Botanic Gardens Department. ↩︎

- DiMichele, William A., and Howard J. Falcon-Lang. 2011. “Pennsylvanian ‘Fossil Forests’ in Growth Position (T0 Assemblages): Origin, Taphonomic Bias and Palaeontological Insights.” Journal of the Geological Society, London 168 (February): 585–605. ↩︎

- Gastaldo, Robert A. 1986. “Implications on the Paleoecology of Autochthonous Lycopods in Clastic Sedimentary Environments of the Early Pennsylvanian of Alabama.” Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 53, nos.2–4 (March): 191–212. ↩︎