When I was younger and more optimistic, I decided that a good way to understand biblical history would be to map out the biblical genealogies in a giant family tree. After creating the family tree, I planned to determine when each person lived. I ended up with 3 x 5 notecards covering the entire floor, and I had barely scratched the surface of biblical chronology. And trying to figure out when each person lived proved impossible for me. The more I read about ancient historical timelines, the more confused I got. Each historian seemed to have a different chronology of ancient history, and every biblical historian had a different idea of when the biblical event fit into those timelines of secular history

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

Difficulties in Dating Biblical Events

The confusion is understandable. After all, biblical history took place thousands of years ago. Beyond the biblical text, we only have two information sources for those periods: ancient texts and archaeological finds. Both of those sources are very fragmentary. Furthermore, ancient texts often consist of royal records that likely contain a strong bias. Archaeology also faces difficulties. Sometimes archaeologists can link archaeological strata with known historical events. But other times, all they can achieve is a relative chronology (i.e. at a certain site, Stratum B represents an occupational period that occurred after Stratum A and before Stratum C).

Generally speaking, the more recent an event, the easier it is to figure out exactly when it happened. There have been fewer intervening years for written records and archaeological finds to become lost or destroyed.

When it comes to biblical history, researchers have established reasonably secure dates as far back as Solomon’s time, in the early 10th century BC.1 Events that happened before Solomon’s time are more difficult to pinpoint. Even using the numbers in the biblical text is difficult, since some data may be missing. After all, the Bible is not a complete chronological history book. It is a theological text that includes historical details.

Dating the Exodus

The Exodus represents a major event in biblical history. The Exodus is a linchpin date for establishing the dates of other events before and after it. The Exodus consisted of a large movement of people from one continent to another. Surely such a significant event should leave its mark on the archaeological record, and perhaps even appear in historical documents from the time.

Archaeologically, evidence for the Exodus might appear in Egypt, reflecting the aftermath of the plagues and the Israelites’ departure. Evidence might also appear in Canaan in the form of destroyed Canaanite cities and new settlements by the Israelites. It is possible, but less likely, for evidence to come to light of the Israelites during their forty years of wilderness wanderings. This is because nomadic populations do not leave very much physical evidence behind.

Because of all the potential sources of evidence, the Exodus should be easy to find in the archaeological record. Yet, views vary widely on when the Exodus occurred. Proponents of each viewpoint can also cite evidence that seems to support their views.

There are two main views on the date of the Exodus, as well as several variations on those dates. A few other ideas exist that are less widely accepted. We will consider the two main views: the Early Date Exodus and the Late Date Exodus. Both find a foundation in scripture.

The Early Date Exodus

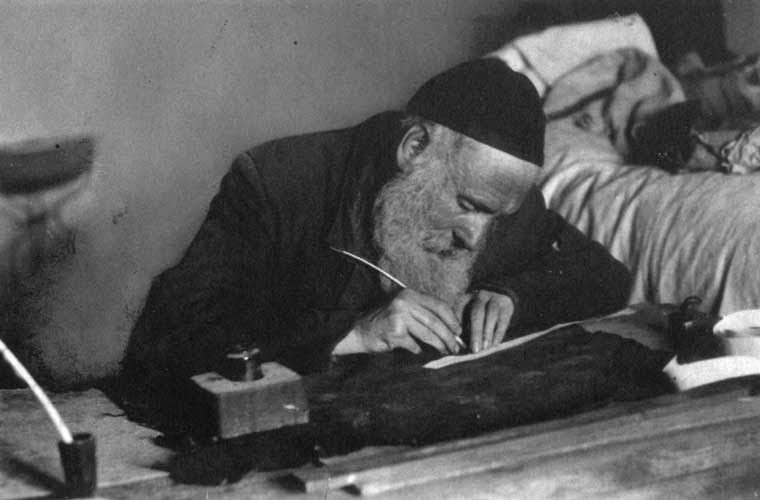

The Early Date Exodus was the predominant view among biblical scholars for centuries. In the 1650s, archbishop James Ussher published The Annals of the World.2 In this impressive text, he traced a biblical timeline from Creation through the reign of the Roman emperor Vespasian. Ussher dated the Exodus to 1491 BC. Although Ussher’s work was impressive, it did contain some errors, particularly in his timeline of the kings of Judah. More recent work, particularly that of Edwin Thiele, refined Ussher’s dates.3 Today, the commonly accepted date for the Early Date Exodus is 1446 BC.

The Early Date Exodus finds its biblical basis in 1 Kings 6:1, which says, “In the four hundred and Eightieth year after the people of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, he began to build the house of the Lord.” Since the text specifies the 480th year, 479 complete years have passed. The dates for Solomon’s reign are well established. This is due to Solomon’s interactions with other historical characters in the Ancient Near East. Scholars have pinpointed the year that Solomon began building the temple as 967 BC.4 From that point, the math is easy. 967 BC + 479 years = 1446 BC. The Israelites wandered in the wilderness for 40 years. That means that they entered the Promised Land in 1406 BC. Judges 11:26 corroborates this date, since Jephthah, who lived around 1100 BC, noted that Israel had settled the land 300 years earlier.

The Early Date Exodus in Egypt

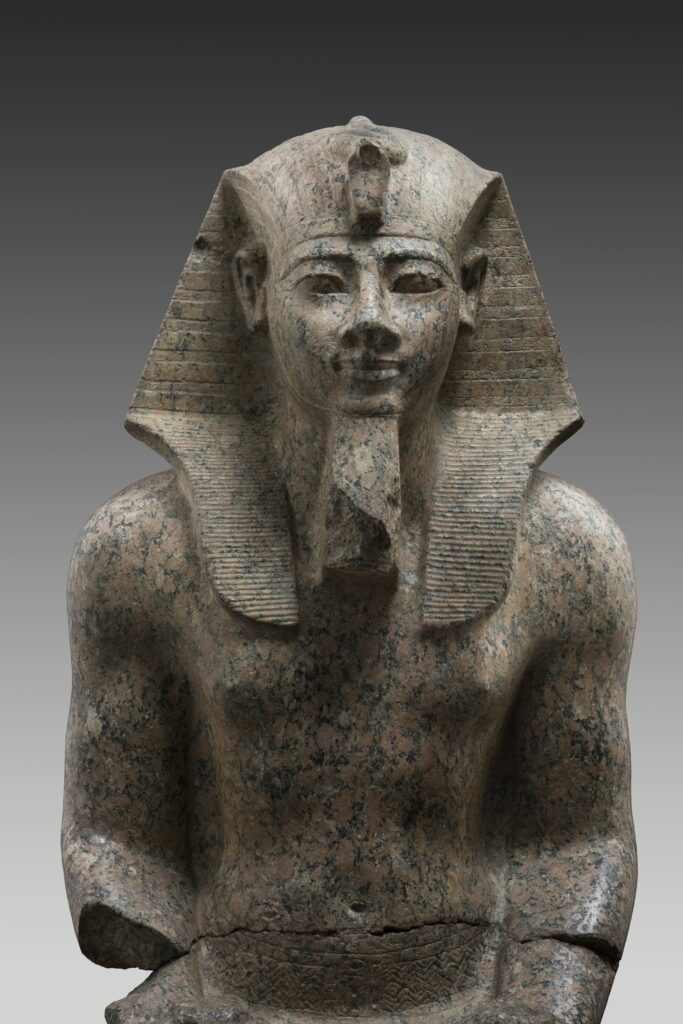

In Egypt, the Early Date Exodus places the Exodus in the 18th dynasty. Ahmose, the founder of the 18th dynasty, and his successors undertook massive building projects at Avaris.5 These projects were powered by slave labor. They likely reflect the years of oppression and slavery that the Israelites suffered in Egypt (Exodus 1:8–14).

Most scholars who hold to the Early Date Exodus believe that Amenhotep II was the pharaoh of the Exodus.6 During his reign, Egypt’s power weakened considerably. The city of Avaris had a large population of Asiatics. The term Asiatic refers to a people group from the area northeast of Egypt, including Canaan. That means that the Israelites were Asiatics. During the reign of Amenhotep II, Avaris entered a period of abandonment,7 perhaps reflecting the Israelites’ departure from Egypt. There are no known documents from the 18th dynasty mentioning the Exodus or the plagues, which some people think is odd. However, this is not surprising, since Egyptians tended to document their successes rather than their failures.

The Early Date Exodus in Canaan

In Canaan, the Early Date Exodus places the Conquest in the Late Bronze Age. At this point in history, Canaan was divided into city-states. These city-states functioned loosely under Egyptian control. They paid taxes to Egypt, but Egypt did not have a large presence in the land.8 This matches well with the descriptions in Joshua and Judges which describe kings ruling over cities and their surrounding villages. However, there does not seem to be much, if any, archaeological evidence for the Israelites settling in the land of Canaan until around 1200 BC, which presents a problem for the Early Date Exodus.

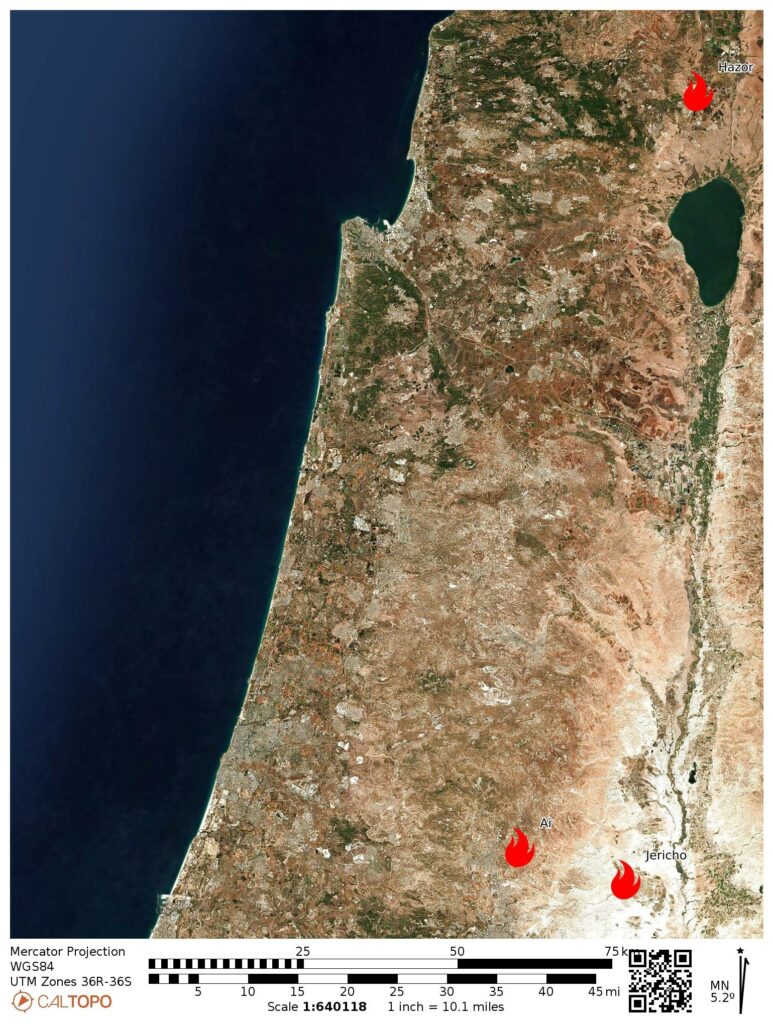

The book of Joshua specifies three cities that the Israelites burned during the conquest: Jericho, Ai, and Hazor (Joshua 6:24; 8:19–20; 11:11, 13). At Jericho, archaeologists found evidence of a huge, fiery destruction of the city. There has been some debate about the date of the destruction. Some archaeologists believe that it dates to around 1400 BC, while others place the destruction earlier, around 1550 BC.9 Et-Tell, the site traditionally identified as Ai, was not occupied at the time of the conquest. However, a nearby site, Khirbet el-Maqatir, fits the biblical qualifications for Ai, and it was destroyed around 1400 BC.10 Archaeologists at Hazor found multiple destruction layers. One of the destructions dates to around 1400 BC.11 Thus, there is potential evidence for fiery destructions at all three sites mentioned in Joshua as being burned.

The Late Date Exodus

Egyptologist Richard Lepsius first proposed The Late Date Exodus view in the 1840s. Almost a century later, W.F. Albright popularized the view among biblical archaeologists.12 Proponents of the Late Date Exodus do not agree on a precise date for the Exodus, but most of their suggestions fall within the 13th century BC, with the Exodus occurring around 1260 BC and the Conquest around 1220 BC.

The Late Date Exodus finds its biblical basis in Exodus 1:11, which states, “Therefore they set taskmasters over them to afflict them with heavy burdens. They built for Pharaoh store cities, Pithom and Raamses.” This passage suggests a link between the Israelites and the 19th dynasty in Egypt, specifically with Pharaoh Ramesses II and the construction of his royal city of Pi-Ramesses next to the ruins of Avaris. Ramesses II reigned from 1279–1213 BC. His predecessor, Seti I, had a summer palace at the location of Pi-Ramesses. However, the construction of the city itself did not occur until during the reign of Ramesses II.

The Late Date Exodus in Egypt

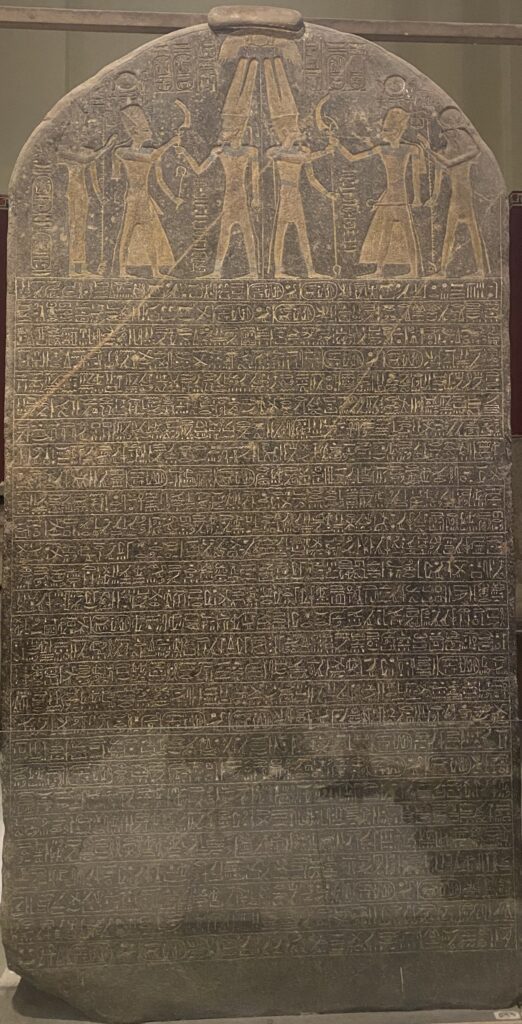

In Egypt, the Late Date Exodus places the Exodus in the 19th dynasty, during the reign of Ramesses II. The timeframe for the Late Date Exodus is narrow. It cannot have occurred after the reign of Ramesses II, or even late in his reign, because his successor, Merneptah, recorded a campaign in which he encountered Israel and referred to them as an established people group in the land of Canaan. On the other hand, the Exodus cannot have occurred before the reign of Ramesses II, since he ordered the construction of Pi-Ramesses. Thus, in this view, it seems that Ramesses II functioned as both the Pharaoh of the Oppression (Exodus 1:8–14) and the Pharaoh of the Exodus (Exodus 2:23).

The Late Date Exodus in Canaan

During the 13th century BC, cities were few and far between in the land of Canaan, especially in the central hill country. However, the land was not devoid of population. Rather, it was home to nomadic people who did not leave a mark on the archaeological record. These people are described in ancient texts as the Habiru.13 Around 1200 BC, hundreds of small towns sprang up, which scholars generally attribute to the arrival of the Israelites. This seems to work well with the Late Date Exodus, occurring about 20 years after the conquest.

Of the three cities that Joshua describes the Israelites destroying with fire (Joshua 6:24; 8:19–20; 11:11, 13), only one has a destruction layer dating to anywhere near the Late Date Exodus. Jericho was not occupied in the 13th century BC, nor was any candidate site for Ai. Hazor suffered a major destruction by fire around 1230 BC.14 This is about 10 years too early to work well with the Late Date Exodus view.

Resolving the Contradictions

It should be clear by this point that each view of the Exodus works well in some respects, but also has some problems. How do proponents of each view resolve these problems?

Problems for the Early Date Exodus

The main problems for the Early Date Exodus are the mention of Raamses in Exodus 1:11 and the lack of evidence for Israelite settlement in Canaan in the 14th century BC. Proponents of the Early Date Exodus have answers for both of these problems.

Over thousands of years, scribes painstakingly copied the Bible by hand, taking precautions to avoid errors. Yet, occasionally they purposely updated the text, particularly in the case of place names. When the name of a city or region changed, scribes would update the biblical text to reflect the new name of the place. This helped the readers to understand the text. Examples of this type of scribal update appear in Genesis 14:14 and 1 Kings 13:32.15 In the case of Exodus 1:11, proponents of the Early Date Exodus suggest that the name is a scribal update that reflects the name change from Avaris to Pi-Ramesses.16

Regarding the lack of evidence for Israelite settlement in Canaan before 1200 BC, proponents of the Early Date Exodus point to the nomadic nature of the Israelites. From the time of Abraham onward, the Israelites were nomadic shepherds. Since they didn’t build permanent structures, they did not leave a visible mark on the archaeological record. However, they do appear in ancient texts from the time. The Amarna letters refer to a people group known as the Habiru, who were nomads and outsiders. These were likely the Hebrews.

Problems for the Late Date Exodus

The Late Date Exodus has its own set of problems. These include the number of years mentioned in 1 Kings 6:1, the need to conflate the Pharaoh of the Oppression with the Pharaoh of the Exodus, and the lack of evidence for the destruction of Conquest cities.

1 Kings 6:1 states that Solomon began constructing the temple in the 480th year after the Exodus. Since the dates for Solomon’s reign are well established, the math does not support a Late-Date Exodus. However, proponents of the Late Date Exodus suggest that the 480 years are symbolic. They refer to 12 idealized generations of 40 years each. However, this view is difficult to support, since 1 Chronicles 6:33–37 lists 18 generations between the Exodus and David (thus 19 generations to reach the time of Solomon).

With the Late Date Exodus, it is necessary to conflate the Pharaoh of the Oppression and the Pharaoh of the Exodus. Ramesses II must be the Pharaoh of the Oppression because the construction of Pi-Ramesses occurred under his reign. But he must also be the Pharaoh of the Exodus. This is because his successor, Merneptah, encountered Israel in the land of Canaan, meaning that the Exodus had already occurred by his reign. However, Exodus 2:23 specifies that the king of Egypt died while Moses was in Midian. I am not aware of any proponents of the Late Date Exodus view who have resolved this problem, although some may suggest that the building projects began during the reign of Seti I, thus making him the Pharaoh of the Oppression.17

Regarding the lack of evidence for the destruction of Conquest cities, proponents of the Late Date Exodus view tend to focus on the sites that have evidence of destruction rather than those that do not. However, by doing so, they end up with a conquest of sites that are very different from those specified in Joshua and Judges.

Conclusion

The Exodus was a major event in biblical history. Yet, the archaeological evidence for the Exodus is less than conclusive, allowing for multiple theories regarding its date. Additionally, biblical passages regarding the Exodus seem to be contradictory (1 Kings 6:1 vs. Exodus 1:11). In my view, the Early Date Exodus is the preferable view on both counts.

First, although the archaeological evidence is sparse, it seems to support the Early Date Exodus. This includes the abandonment of Avaris during the reign of Amenhotep II. It also includes the destruction of Jericho, Ai, and Hazor as described in the Bible. Additionally, the historical references to the Habiru seem to refer to the Israelites as nomadic peoples living in the land during the 14th century BC.

Second, I believe the Early Date Exodus fits better within the biblical text since a literal reading of most passages supports this view. The only seeming discrepancy is the name of the city Raamses in Exodus 1:11. However, this can be attributed to a scribal update. On the other hand, linguistic gymnastics are necessary in multiple instances to make the biblical text support the Late Date Exodus.

For these reasons, the Early Date Exodus seems to be the preferable view. However, it can be dangerous to remain dogmatic on views that are not 100% certain. A good scholar should remain open to examining various viewpoints and adjust as new evidence comes to light. After all, good scholarship requires humility. A biblically-minded scholar should be more concerned with finding the truth than proving his or her viewpoint.

Footnotes

- Eames, Christopher. 2022. “967 B.C.E: How the Lynchpin Date for Solomon’s Temple Was Determined.” Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology. ↩︎

- Ussher, James. 1658. The Annals of the World. London: F. Crook and G. Bedell. ↩︎

- Thiele, Edwin R. 1944. “The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 3: 137–186. ↩︎

- Eames, Christopher. 2022. “967 B.C.E: How the Lynchpin Date for Solomon’s Temple Was Determined.” Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology. ↩︎

- Bietak, Manfred. 1996. Avaris: The Capital of the Hyksos: Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dab’a. London: British Museum Press. ↩︎

- Petrovich, Douglas. 2006. “Amenhotep II and the Historicity of the Exodus-Pharaoh.” The Master’s Seminary Journal 17:1. ↩︎

- Petrovich, Douglas. 2013. “Toward Pinpointing the Timing of the Egyptian Abandonment of Avaris during the Middle of the 18th Dynasty.” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 5:2, 9–28. ↩︎

- Moran, William L. (Translator and Editor). 1992. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ↩︎

- Wood, Bryant. 1990. “Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho? A New Look at the Archaeological Evidence.” Biblical Archaeology Review 16:2. ↩︎

- Wood, Bryant. 2008. “The Search for Joshua’s Ai,” in Critical Issues in Early Israelite History, edited by Richard S. Hess, Gerald A. Klingbeil, and Paul J. Ray Jr. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ↩︎

- Petrovich, Douglas. 2008. “The Dating of Hazor’s Destruction in Joshua 11 via Biblical, Archaeological, and Epigraphical Evidence.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 51:3, 489–512. ↩︎

- Albright, W.F. 1934. “The Kyle Memorial Excavation at Bethel.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 56:1–15. ↩︎

- Moran, William L. (Translator and Editor). 1992. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ↩︎

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. 2003. “An Egyptian Inscribed Fragment from Late Bronze Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 53:1, 20–28. ↩︎

- Wood, Bryant G. 2005. “The Rise and Fall of the 13th Century Exodus-Conquest Theory.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 48:3, 475–489. ↩︎

- Stripling, Scott. 2021. “The Fifteenth-Century (Early Date) Exodus View.” In Five Views on the Exodus, edited by Mark D. Janzen, 25–52. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. ↩︎

- Hoffmeier, James K. 1999. Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩︎

Why no mention of a major opinion that the Exodus occurred at the time of the 13th Dynasty?

I am aware of the 13th Dynasty view. It is an interesting chronology, but I think it is problematic, especially in relation to Levantine archaeology. I did not include it in the article because it is not a widely held view among biblical scholars.

Thanks for your answer. Also you don’t speak about the traditional Orthodox Jewish date based on the Seder Olam of 1313-2 BC.

Abigail, thanks for your straightforward description of the options and your focus on evidence.

Blessings,

Ken

Thank you, Abigail, for the clear summary of both views. Not being a scholar in either biblical studies or archeology, I have struggled with the conflicting dates in homeschool curriculum. I wish I had this article while trying to rectify the dates myself.

When you compare 1 Kings 6:1 with Josephus and the New Testament, you can clearly see that there’s a problem with this text!

In Antiquities 8.3.1, Josephus wrote:

“Solomon began to build the temple in the fourth year of his reign… five hundred and ninety and two years after the Exodus out of Egypt.”

Obviously, this is 112 years more than the 480 years in 1 Kings 6:1.

But what does the New Testament say? Does the New Testament agree with 1 Kings 6:1 or with Josephus? The New Testament agrees with Josephus. Acts 13:20, 21 says that there were 450 years for the period of the Judges alone. So if the period of the Judges was 450 years, 1 Kings 6:1 must be incorrect. 40 years of wilderness wondering plus 450 years plus 40 years = 530 years, which is closer to Josephus’ date.

Hi Robert, You raise an interesting point. How do we resolve seeming contradictions in the biblical text? You are right to consult other ancient texts, in this case, Josephus. However, Josephus should be taken with caution because he is notoriously inaccurate in his historical writings. For that reason, I don’t give much weight to his figure of 592 years. The Acts 13 passage is also problematic because some ambiguity in the Greek allows for differing translations. Some English translations assign the 450 years to the Judges period, while others assign it to the period that the Israelites spent in Egypt, wandering in the wilderness, and conquering Canaan. Thus, I see no reason to disregard 1 Kings 6:1 based on Acts 13:20. And, even if the two texts were proven to be contradictory (which I don’t think they are), I would favor 1 Kings 6:1 over Acts 13:20 for two reasons. First, 1 Kings was written much closer to when the events took place and should, therefore, be more reliable than Acts. Second, 1 Kings was an official court document documenting events with precision. By contrast, in Acts, Paul verbally recounted the history of the Israelites in a less-than-precise manner, using the qualifier “about” in reference to the 450 years.

Thanks for your reply, Abigail. Why do you say Josephus is “ notoriously inaccurate” in his writings?

Different scholars distrust Josephus to varying degrees. He seems to have been fairly reliable in his eyewitness accounts, although probably somewhat biased. However, when it comes to events to which Josephus was not an eyewitness, he is only as reliable as the sources he used, and then he likely did some editing based on his personal biases. Here are a couple of articles about the reliability of Josephus that I think are fair assessments:

https://answersingenesis.org/bible-history/is-josephus-reliable/

https://library.biblicalarchaeology.org/sidebar/how-reliable-is-josephus/

The Israelites were in Egypt for 215 years and then spent 40 years in the wilderness. This is a total of 255 years.

Now, the alternative reading of Acts 13:19, 20 says that the Israelites were in Egypt, in the wilderness, and conquering Canaan for 450 years. So if Egypt + wilderness = 255 years, did they then spend 195 years conquering Canaan BEFORE the period of Judges?

I really don’t think the book of Joshua contains 195 years of history! Are you seeing this the same way I am?

Therefore, the NKJV translation of Acts 13:20 makes more sense: the 450 years applies after Joshua.

Is it possible that there was a scribal error in 1 Kings 6:1, either deliberate or accidental, which altered 580 years to 480 years? Could the original text have said 580 years?

It’s true that Acts 13:20 uses the word “about”, but Acts 13:18 also uses the word “about” to describe the 40 years of wilderness wondering, which is exactly 40 years in nearly every other Bible reference on this subject.

I suggest that there is a scribal error in 1 Kings 6:1 and that the text originally read “in the 1480th year.” This brings harmony with Paul’s chronology in Acts 13 as well as the chronological data in the book of Judges. More importantly, it correlates with archaeological data for the three major Canaanite cities that were destroyed at the time of Joshua – Jericho, Ai, and Hazor – all of which have fiery destruction layers at circa 2400 BC. There is also evidence for a major people movement through the Sinai desert in the 25th century BC.