Whether you are in the Grand Canyon, hiking in the Appalachian Mountains, or simply driving through roadcuts on the interstate, you will see layers of rock. Each rock layer is made from a different type of material. But what you might not know is that these layers do not appear in a random order. Rather, they exist in predictable patterns we can trace across continents and around the world. In fact, there seem to be five or six major patterns in the geologic record. Many geologists call them “megasequences.”

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author and not necessarily those of the New Creation blog.

Sloss Makes a Mega-Discovery

While the term “megasequence” was first used by geologist Bilal Haq in 1988, the patterns in the geologic record it describes go by many names.1 Some call them “cratonic sequences” or “stratigraphic sequences.” Others even refer to them as “supersequences.” But they are also called “Sloss sequences” after Dr. Laurence L. Sloss, the geologist who first described them. In 1963, he published research showing his colleagues that there were at least five or six large packages of rock layers carpeting the continent of North America and stacked right on top of each other.2,3 Each one was hundreds of feet thick.

What is a Megasequence?

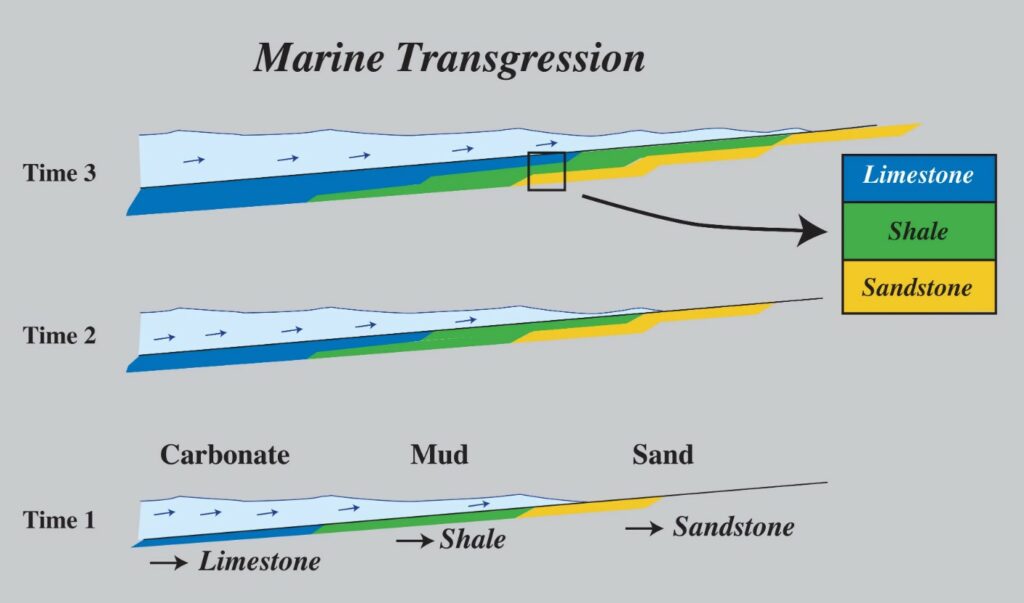

The rock layers within each package are arranged in the same general fashion. A megasequence is a stack of sediments capped above and below by a flat, eroded surface called an unconformity. The sediments in between these unconformities will be arranged by size. The larger particles congregate toward the bottom and the smaller particles congregate toward the top. Typically, the base of the sequence will consist of a conglomerate deposit—perhaps gravel, boulders, or cobbles. Ascending, you will find sandstone, followed by shale, and finally carbonate deposits, like limestone or dolomite, just below the top unconformity. These sequences are not always complete in the field, but whatever sediment particle sizes are present occur in this order.

Since Sloss’ initial work, geologists have identified five or six megasequences covering North America, all named after native American tribes. We can correlate these to the regular geologic column with which we are all familiar. The primary difference is that the geologic column is based on changes of rock and fossil content. Both are valid descriptions of patterns in the geologic record, but they are used to tell geologists different types of information.

Mapping Out the Sequences

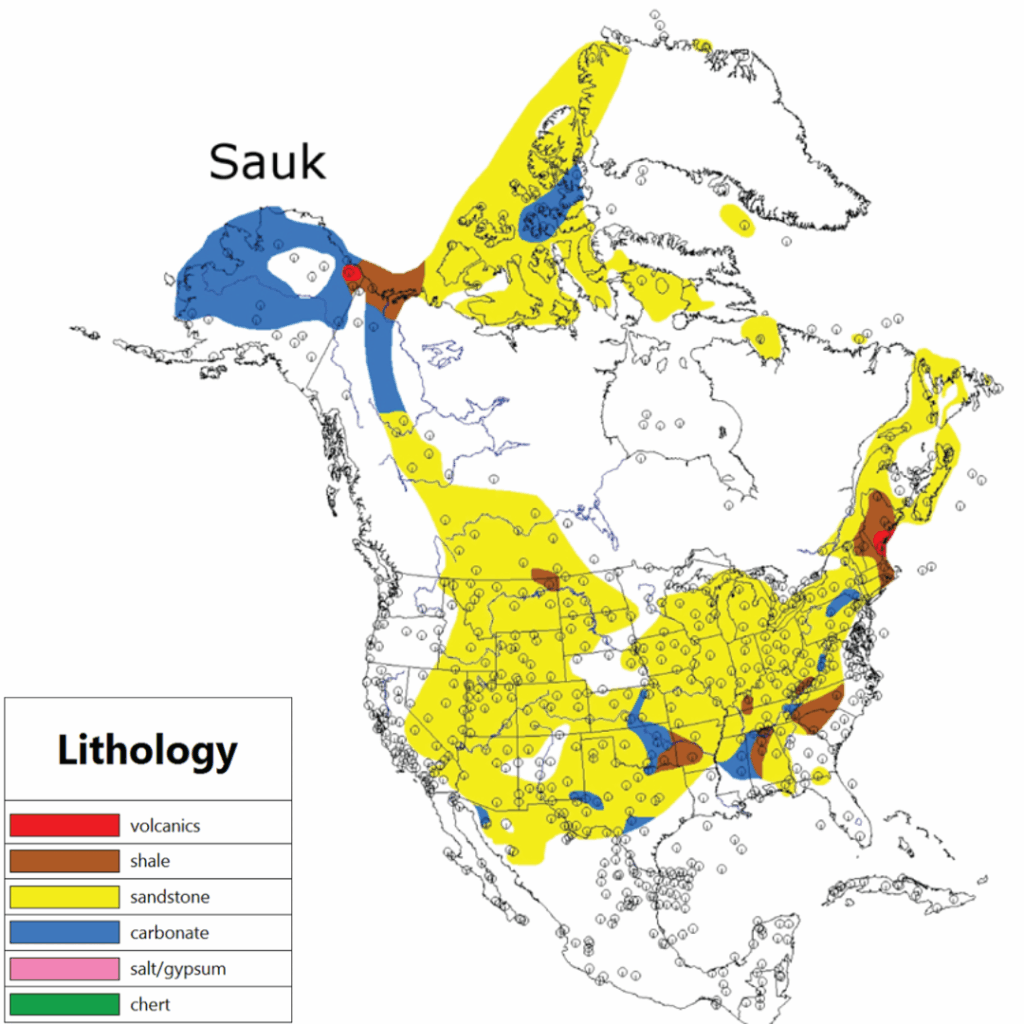

Mapping out the extent and thickness of megasequences can help us understand when and how they formed. They can also tell us a lot about how the sedimentary record of the continents developed over time. Since 2013, geologist Dr. Tim Clarey has been heading up the ongoing Column Project at the Institute for Creation Research.4 The results obtained from this research are obtained from from oil wells, outcrops, and seismic data collected by geologists around the world. The figures below are from the Column Project’s mapping of megasequences across the continent of North America.

Sauk Sequence

The Sauk sequence begins at the Great Unconformity, a flat, two-dimensional surface separating the Sauk sequence itself from the basement rock that is the continent’s core. Meanwhile the Sauk sequence ends in the lower Ordovician deposits. The Sauk sequence covers most of the North American continent, except for parts of the Canadian Shield and a low altitude peninsula or chain of islands known as the Transcontinental Arch. This sequence of strata is famously exposed in the Grand Canyon. We refer to it specifically as the Tapeats Sandstone, Bright Angel Formation, and Muav Limestone. The fossil record in these layers is largely dominated by shallow water marine organisms.

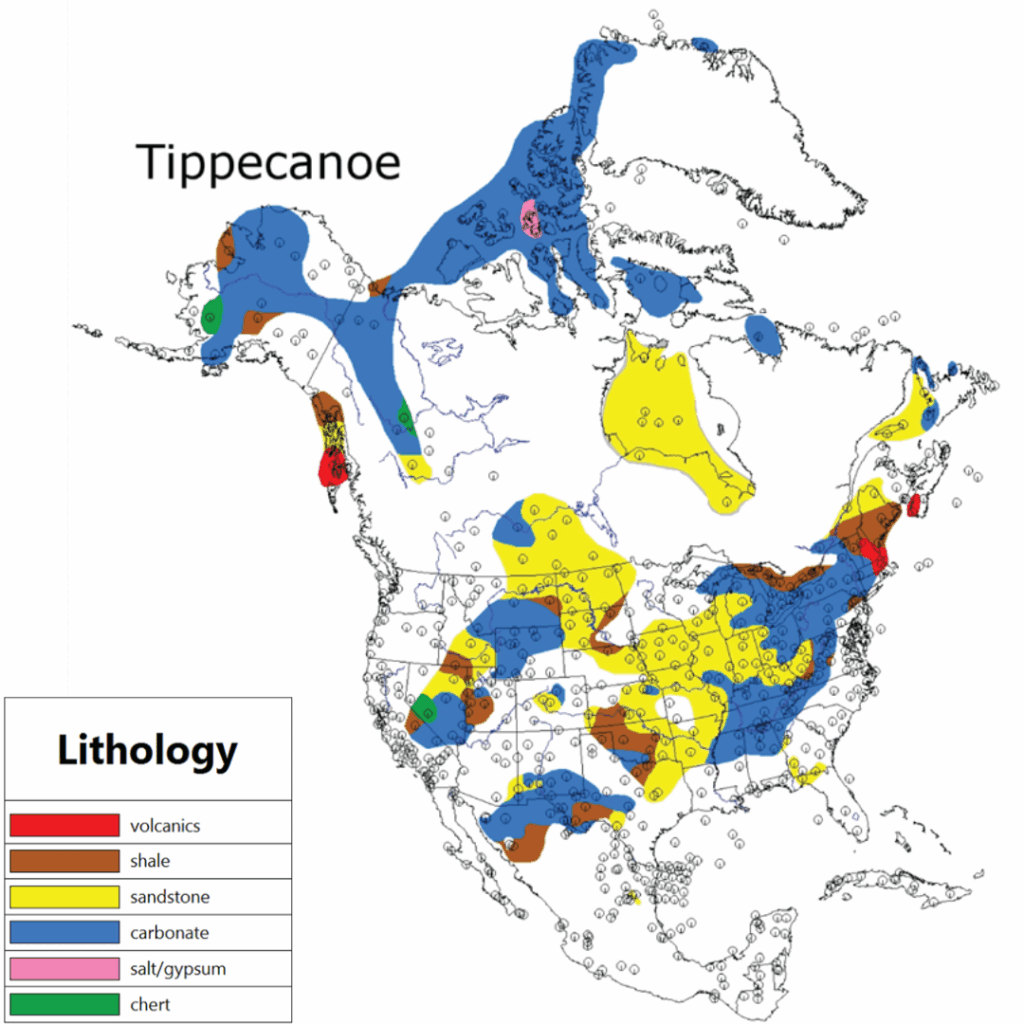

Tippecanoe Sequence

The Tippecanoe sequence roughly correlates from the middle Ordovician to lower Devonian layers of the standard geologic column. It drapes across almost the entire North American continent, except a region known as the Taconic highlands. Like the Sauk, these layers are predominantly home to fossils of marine organisms that inhabited shallow water environments.

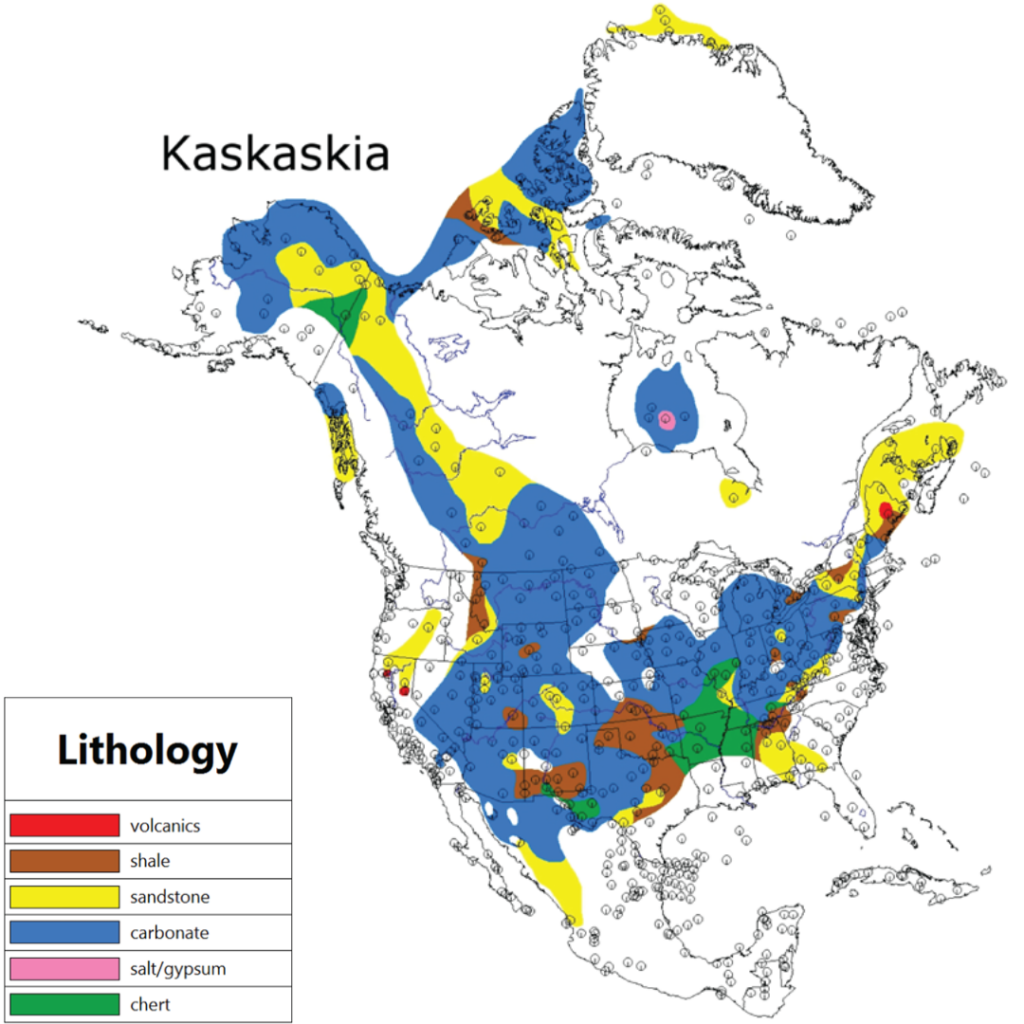

Kaskaskia Sequence

The Kaskaskia sequence approximately begins in the mid-Devonian layers and ascends until the uppermost Mississippian layers. Once again, this sequence stretches across much of the North American continent where a wide range of sediments were deposited. Interestingly, this is also where fossils of land animals and plants begin showing up.

Absaroka Sequence

Increased diversity among fossils of land animals (including dinosaurs) and plants is exhibited in the Absaroka sequence. It begins at about the Pennsylvanian layers and continues until the lower Jurassic layers.

Zuni Sequence

The Zuni sequence is characterized by rock layers ranging from the mid-Jurassic until upper Cretaceous. It is particularly well-developed in the western stretches of North America, extending into the Gulf Coast basin and includes areas of western Canada. The youngest Zuni layers occur in basins of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. This is unofficially the last megasequence recorded in the geologic record.

Tejas Sequence

Technically, the Tejas sequence follows the Zuni sequence, occurring strictly in lower Paleogene layers. However, according to paleontologist Dr. Kurt Wise, it is not a true megasequence because it lacks the telltale signatures of a real megasequence.5 That is, it is not capped by an erosional boundary or carbonate deposits, and the sediment particles making up the layers within it are not sorted from largest to smallest. Additionally, the five true megasequences cover large portions of the North American continent. But the Tejas “sequence” is really only present in the southeast (notice the presence of the limestone carbonate in the figure above).

Why Do Megasequences Exist?

Why is it that North America is covered in a particular sequence of rock layers five times over? Geologists understand megasequences to be the sedimentary packages left behind by a complete cycle of sea level rising and falling over the continent. The size of sedimentary particles can give geologists a clue as to how much energy the water was exerting at the time they were being deposited. It takes a lot more energy to transport a boulder than a tiny grain of mud.

The sequence of the sedimentary package, then, is suggestive of a single depositional sequence, during which the water began with high energy. It moved so fast that everything from boulders to carbonates could not be deposited. They were so powerful that they actively eroded the land surface over which they moved. As the water grew deeper over a given area, its speed and energy decreased over time. This caused larger particles to be dropped first. As the water continued to get deeper and slower, smaller and smaller particles were deposited.

So megasequences each represent a time during which sea levels rose across the continent of North America.

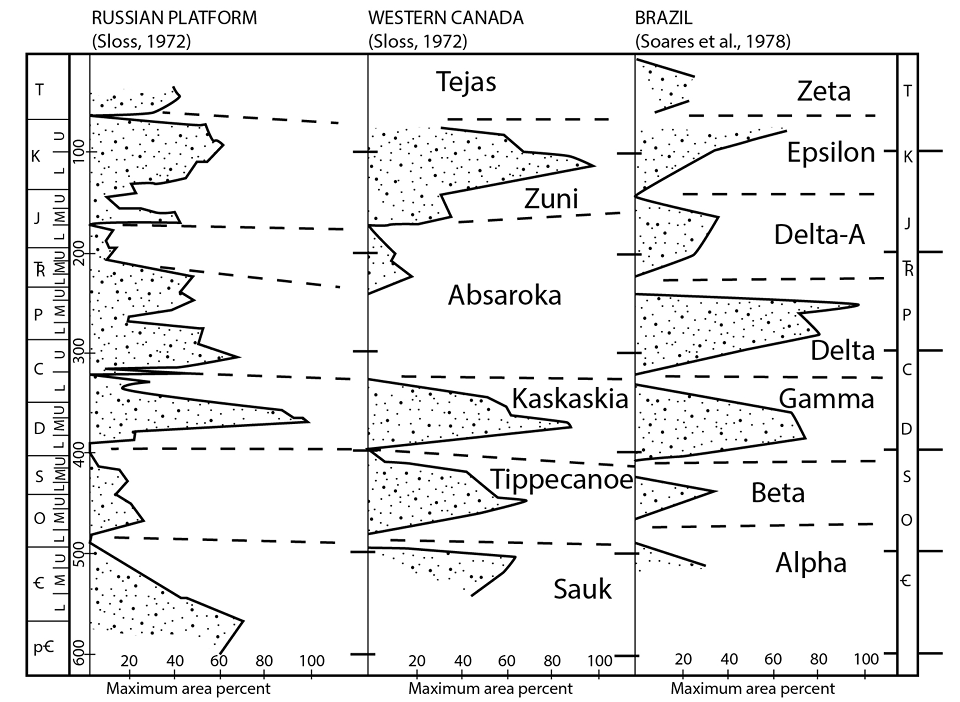

Beyond North America

Sloss’ original work of identifying and mapping megasequences was strictly done in North America. But this is not the only place they can be found. Oil industry geologists working in Brazil, Africa, and on the Russian Platform quickly identified nearly identical patterns that match those found in North America.6 The Column Project also also matches up these patterns in South America, Africa, Europe, and Asia.7 All of this suggests that the changes in sea level reflected by megasequences in North America occurred worldwide at the same time. This makes sense if you think about it: significant changes in sea level cannot only occur in one part of the world, they must be a global phenomenon because water must retain a singular level over its entire extent.

How Did Megasequences Form?

The existence of megasequences demands an explanation for their existence. Short of adding and removing large quantities of water from the oceans, there must have been some force capable of pushing the ocean waters onto continents not once or twice, but five times. What was it?

It probably has something to do with the rate at which seafloor spreading occurs. The ocean floor is actively created and spread outwards by a series of volcanic mountain ranges running along the bottom of the ocean like seams on a baseball. This is called the mid-ocean ridge system. Newly created seafloor is hot and more buoyant than older, colder seafloors farther away from the ridges.

When the rate of seafloor spreading increases, it creates lots of hot and buoyant seafloor, shallowing the ocean basins. The seawater has nowhere to go but up and onto the continents as a result. When seafloor spreading rates decrease, mid-ocean ridges sink down and the seawater drains off of the continents. For a more in-depth discussion of this topic, please see our article on plate tectonics.

Why Do Creationists Care About Megasequences?

Most young-age creationists believe the majority of the geologic record was the product of a supernatural Creation Week and a global Flood in the days of Noah. Megasequences speak of crustal forces that controlled the carpeting of thick packages of continental sediments on a global scale. It should be easy to see why this is exciting for creationists! By studying megasequences, young-age geologists can get a better understanding of how the Earth’s geologic record was formed over the course of its history. The study of megasequences is an ongoing area of research by young-age geologists. This will help them model sea level fluctuations during the Flood and how various sedimentary layers were formed.

Conclusion

Sloss probably had no idea just how much his “mega” discovery would change his field of study in the decades that followed. These five repeating sequences of sedimentary rock blanketing the continents speak of powerful surges of water that completely reshaped the Earth’s surface. Each one suggests an enormous inundation of water that left thick layers of boulders, sand, mud, and carbonates in their wake. Nothing like this is happening across the continents today.

By continuing to study megasequences, young-age geologists hope to increase their understanding of exactly what large-scale, catastrophic processes were at work during the globe-encompassing Flood of Noah’s day.

Footnotes

- Haq, B.U., J. Hardenbol, and P.R. Vail. (1988). “Mesozoic and Cenozoic chronostratigraphy and cycles of sea-level change. In Sea-Level Changes: An Integrated Approach.” SEPM Special Publication 42:71108. ↩︎

- Sloss, L. L. (1963). “Sequences in the cratonic interior of North America.” Geological Society of America Bulletin, 74(2), 93-114. ↩︎

- Sloss, Lawrence L. (1964). “Tectonic Cycles of the North American Craton.” Symposium on Cyclic Sedimentation: Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 169. pp. 449-459. ↩︎

- Clarey, T.L., & D.J. Werner. 2018. “Global stratigraphy and the fossil record validate a Flood origin for the geologic column.” In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism, ed. J.H. Whitmore, pp. 327–350. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship. ↩︎

- Wise, K.P. and Richardson, D. (2023) “What Biostratigraphic Continuity Suggests About Earth History,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 9, Article 19. ↩︎

- Soares, P.C., P.M. B. Landim, and V.J. Fulfaro. (1978). “Tectonic cycles and sedimentary sequences in the Brazilian intracratonic basins.” Geological Society of America Bulletin 89, no. 2:181-191. ↩︎

- Clarey, Timothy L. and Werner, Davis J. (2023). “A Progressive Global Flood Model Confirmed by Rock Data Across Five Continents,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 9, Article 23. ↩︎