When we think of the events of Creation Week, it’s the creative acts of Days 3 through 6 that most often come to mind. Plant life, stars and planets, birds and fish, dinosaurs, people — you know, all the exciting stuff. But on Day 2 there’s the quiet little account of the creation of the “expanse.” This divided the primordial water into two domains: the waters above the expanse and the waters below.

“Then God said, ‘Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.’ So God made the expanse and separated the waters which were below the expanse from the waters which were above the expanse; and it was so. And God called the expanse heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day.” – Genesis 1:6-8 (ESV)

It’s understandable that the creation of empty space gets less attention than the creation of dinosaurs. But a close look at this brief account raises an interesting question. We know what happens to the waters below the expanse. On Day 3, God gathers them into one place and names them the Sea. But what about the waters above the expanse? Where exactly did they end up? Are they still out there, somewhere?

It turns out that any understanding of the “waters above” must begin with the expanse itself – what it is, and where it is. Only when we have defined the expanse can we begin to define the waters in relation to that expanse.

And it turns out, further, that the definition of the expanse is complicated. There are three broad interpretative categories in which we could place definitions of the expanse, for the purposes of this discussion.

The Solid Expanse

We begin with an interpretation which has a long history reflected in our English translations of the Bible (of all places!). It defines the “expanse” as something much like Greek cosmology. This idea was a hard, crystalline sphere to which the sun, moon, and stars are affixed. It appears that the translators of the Greek Old Testament interpreted the Hebrew “rāqîa” in terms of the cosmology of their day. They translated the word accordingly as “stereoma”.1 The Latin Vulgate, translated from the Greek, carried on this interpretation with its rendering “firmamentum.” Readers familiar with the King James Version may recognize this word. It is the term behind the KJV’s “firmament” in the first chapter of Genesis. At the time of the Greek translation of the Old Testament, this understanding of the expanse was a way to accommodate contemporary scientific understanding with Scripture.

This translational history has led some to assume that Genesis 1 was advocating a hard-dome cosmology as a reflection of its Ancient Near Eastern context. Seely posits that “all peoples in the ancient world thought of the sky as solid.” He therefore concludes “we have every reason to think that both the writer and original readers of Genesis 1 believed the rāqîa was solid.”2 Seely’s position is that the Bible merely reflects the cosmological understanding of ANE cultures.

In contrast, Kulikovsky points out that the Israelites had more sophisticated knowledge of the world than Seely would have us believe. For one thing, there is evidence in the book of Job. For example, Kulikovsky points out that “in contrast to virtually all ancient cosmologies,” Job 26:7 says that God “hangs the earth on nothing.” Kulikovsky further argues that Israel was an isolated cultural identity, given that they lived in the land of Goshen for centuries. We have little reason to think the nation had any interest in other contemporary cosmologies–especially when those cosmologies countered their own traditions.3

The Word Behind Expanse

As it turns out, the Hebrew word translated as “expanse”/“firmament”/et cetera doesn’t necessarily carry the meaning of solidity. Rather, the noun “rāqîa” derives from the root verb “raqa,” which means “to expand, spread, stretch.” The verb “raqa” is used in the building of the tabernacle. This is when the Israelites hammered gold into thin sheets for covering the sacred furniture. Thus, while the verb “rāqîa” is used in the context of hard solid material, it speaks to expansion as well.

Let us take into consideration the references in Scripture to God “stretching out” the heavens (Job 9:8, Isaiah 40:22, et cetera). Recall that the heavens (shamayim in Hebrew) are identified with the “rāqîa” in Genesis 1:8. It then makes sense to see the noun “rāqîa” as denoting something that has been stretched out, an expanse.4 So, when we factor out the more recent history of translation in the Hellenistic period, the translation “expanse” makes better interpretive sense than the translation “firmament.” (For ease of reading, we will use the term “expanse” in place of the Hebrew “rāqîa” from this point on.)

The Atmospheric Expanse

A simpler, and perhaps more common, interpretation of the Day 2 account defines the expanse as the earth’s atmosphere. This interpretation understands the “waters above the expanse” as water vapor in the atmosphere, in the form of clouds. John Calvin describes it this way:

We see that the clouds suspended in the air, which threaten to fall upon our heads, yet leave us space to breathe. . . . Since, therefore, God has created the clouds, and assigned them a region above us, it ought not to be forgotten that they are restrained by the power of God, lest, gushing forth with sudden violence, they should swallow us up: and especially since no other barrier is opposed to them than the liquid and yielding, air, which would easily give way unless this word prevailed, “Let there be an expanse between the waters.”5

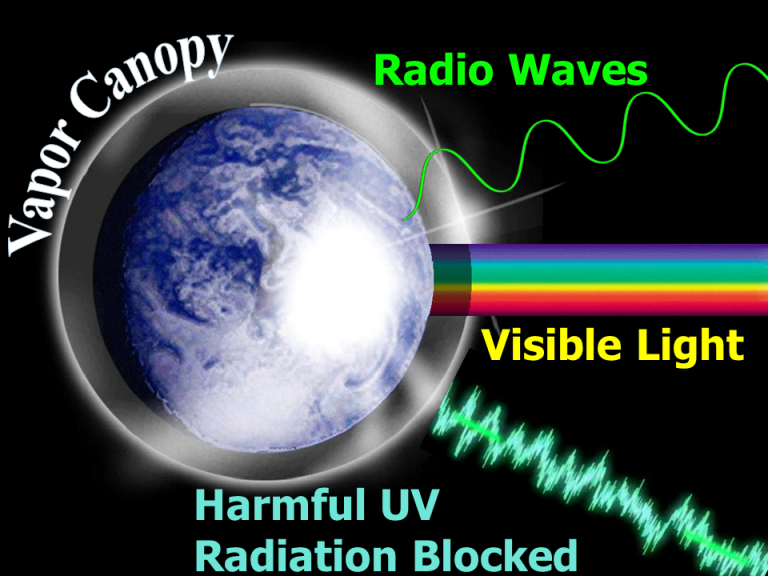

Within this interpretive category we may also place the vapor canopy. Whitcomb and Morris first postulated this. This theory enjoyed considerable popularity for many years in creationism. Like the first view, this interpretation held that the expanse is the earth’s atmosphere. It also postulated that the waters above the expanse formed a massive layer of water vapor above the earth’s atmosphere. This vapor canopy regulated the earth’s temperature and provided other benefits to the antediluvian world. Then it collapsed to form the major source of water for the Noahic Flood.

The vapor canopy theory suffered from both biblical and scientific issues. These led to its broad rejection among creation scientists. One major Biblical issue for the vapor canopy is Psalm 148:4. It speaks of “the waters above the heavens” as still in existence well after the Flood. As a scientific model, the vapor canopy suffers from the greenhouse effect. The water vapor in the atmosphere in this model had to be enough to cover the Earth during Noah’s Flood. However, that would create temperatures on Earth’s surface that are inhospitable to life.6

Where in the Expanse?

There is one biblical issue raised with the general atmospheric interpretation (and which also applies to the vapor canopy). This is the location of the sun, moon, and stars in relation to the expanse. Genesis 1:17 says that God placed the heavenly bodies “in the expanse of the heavens.” This seems to rule out any atmospheric interpretation of the expanse.

In response, however, proponents of the atmospheric expanse posit that this can be an example of phenomenological language. According to this view, the heavenly bodies are not actually spatially located in the expanse. However, they do appear to be within the expanse. Thus it is accurate to say they are within the expanse. There is a difficulty with this phenomenological understanding, though. If the clouds are above the expanse –and the sun, moon, and stars are within the expanse– this would seem to imply that, phenomenologically speaking, the sun, moon, and stars appear to be in the sky below the clouds, which is certainly not the case.

Across the Face of

Furthermore, a close look at God’s creative command on Day 5 sheds further light on the nature of the expanse and its relationship to the atmosphere. Genesis 1:20 reads, “let birds fly above the earth across the face of the expanse of the heavens” (LSB). The key here is the phrase “across the face of the expanse of the heavens.” The Hebrew behind this phrase reads “al penê reqia‘ hashshamayim‘.” Mortenson’s helpful discussion of this matter compares several translations of this verse. It finds that most translations render this passage less literally. A typical rendering is the NASB 1995’s “let birds fly above the earth in the open expanse of the heavens.”7 This imprecise rendering obscures the meaning of the phrase. It does not translate the phrase “al penê,” which literally means “across [the] face of”.

What does it mean for birds to fly across the face of the expanse? We should notice that the phrase rendered as “across the face of” here one Day 2 is used elsewhere in the Creation Week account. In Genesis 1:2, this Hebrew phrase “al penê” speaks of the darkness “over the surface of the deep.” It is also behind “the Spirit of God… hovering over the surface of the waters.” Thus, it appears that we can understand the birds in relation to the expanse in the same way that the darkness covered the deep, and the Spirit hovered over the waters. The birds are not in the expanse. Rather, they are on the surface of it, as viewed from the surface of earth.

Mortenson raises an interesting point on this by looking at Psalm 148. It mentions the “waters above the heavens” (verse 4). Mortenson points out the Psalm’s division between praise “from the heavens” in verses 1-6 and praise “from the earth” in verses 7-14. He then notes that the birds are included in the section focusing on praise from the earth. Likewise, it is in this section the Psalm writer chooses to place the atmospheric phenomena such as wind and clouds. Thus, the Psalmist puts atmospheric phenomena and birds in a separate category fro the expanse. This further supports the idea that the expanse is referring to interstellar space, perhaps to the exclusion of the atmosphere.

The Cosmic Expanse

The final interpretive category defines the expanse as interstellar space. This definition of the expanse understands the waters above to be a cosmic phenomenon. Humphreys first began popularizing this interpretation in his book Starlight and Time.8 Since then, other creation scientists have begun implementing this interpretation in their cosmological models.9,10 This takes a literal approach to the idea that God placed the celestial bodies, created on Day 4, in the expanse.

This interpretation also means that interstellar space itself is part of the created universe. It is a created thing in and of itself. It’s easy to consider “outer space” as simply the absence of something. But with the rise of modern physics, particularly Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, we’ve come to understand that space itself is, in fact, something.

To be clear, this interpretation is not simply a convenient way to make the Bible fit with science. It’s also consistent with the way the Bible speaks about the universe. Throughout the Bible, it speaks of the heavens – space – as an entity, as something more than the absence of something. (Specifically, the idea of “stretching out the heavens” appears in many places. Job 9:8, Psalm 104:2, Isaiah 40:22 are just a few examples). Thus, the cosmic interpretation of the expanse, as proposed by Humphreys in Starlight and Time, is applying a more literal hermeneutic to the Day 2 account (as opposed to phenomenological approaches such as the atmospheric interpretation).

One biblical issue raised with this interpretation is the fact that Genesis says the flying creatures on Day 5 fly in the expanse. Birds don’t fly in interstellar space. The response to this is twofold. On the one hand, as discussed previously, the Hebrew grammar of this construction appears to be saying the birds are on the surface of the expanse as seen from earth. Some modern translations reflect this, such as the Legacy Standard Bible. It renders Genesis 1:20 as “let birds fly above the earth across the face of the expanse of the heavens.”

On the other hand, as Faulkner points out, the ancient Hebrew conception of “the sky” was likely not as nuanced as our modern conception. It did not have a distinction between the atmosphere and interstellar space like we do. Rather, birds would have been considered as inhabiting the same sky through which the Sun moves.

So, What About The Waters Above The Expanse?

As mentioned before, each of these interpretations of what God created on Day 2 have differing implications for the waters above the expanse. In the solid expanse view, the waters outside the “firmament” would likely be the cosmic ocean in which the flat earth resides. For the atmospheric approach, the waters are either water vapor in the earth’s atmosphere, or a pre-Flood vapor canopy. And from the cosmic expanse interpretation, the logical implication is that the waters above the expanse are to be found at the outer edge of the universe.

It turns out that this latter interpretation has major implications for creation astronomy. But we’ll save those implications for Part 2.

Footnotes

- Younker, R. W., and R. M. Davidson. (2011). “The Myth of the Solid Heavenly Dome: Another Look at the Hebrew רָקִיעַ (rāqîaʿ).” Andrews University Seminary Studies 1:125–147. ↩︎

- Seely, P. H. The Firmament and the Water Above Part I: The Meaning of rāqîaʿ in Gen. 1:6-8. WTJ 53/2 (Fall 1991), 227-240 ↩︎

- Kulikovsky, Andrew S. (2009). Creation, Fall, and Restoration. Mentor. 130-132 ↩︎

- Vauterlaus, G. (2009). “Underneath a Solid Sky.” In Ham, Ken (ed.), Demolishing Supposed Bible Contradictions Volume 1. Master Books ↩︎

- Calvin, J. 1992. Genesis. Reprint of John King’s 1578 English translation of Calvin’s original 1554 Latin text. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Banner of Truth. ↩︎

- Vardiman, L. and Bousselot, K. (1998). “Sensitivity Studies on Vapor Canopy Temperature Profiles,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 4, Article 51. ↩︎

- Mortenson, T. (2020). The Firmament: What Did God Create on Day 2?. Answers Research Journal 13(2020):113–133. https://answersresearchjournal.org/firmament-what-did-god-create-day-2/. ↩︎

- Humphreys, D.R. (1994). Starlight and Time. Master Books ↩︎

- Hartnett, J. G. (2007). Starlight, Time, and the New Physics. Creation Book Publishers ↩︎

- Faulkner, D. R. (2016). Thoughts on the rāqia‘ and a Possible Explanation for the Cosmic Microwave Background. Answers Research Journal 9(2016):57-65 ↩︎

This was an informative and interesting article. However, I remain unconvinced. I don’t believe you adequately engaged with the firmament thesis. In your attempt to critique it, you correctly note that the Bible’s use of the noun “raqia” comes from the verb “to expand, spread, stretch” in order to convey the idea of the heaven being stretched out, but also argue that this doesn’t speak of something firm and solid being stretched out when referring to the sky. But why? You already acknowledged that the Bible can mean both, such as in reference to the building of the Tabernacle with the stretching/expanding of solid gold material. But for some reason, you want to ignore the solid aspect and focus only on its expanding qualities when it talks about the heavens. In fact, you ignore the fact that it always means both. Every time the Bible talks of the nature of the heavens being stretched, it is always compared to something corporeal. You cite Job as being scientifically advanced, but you neglect to mention Job 37:18, which explicitly depicts the sky as hard or firm.

In any event, while I disagree with this article, I very much enjoyed reading it and look forward to reading more of your thoughts.