The Hebrews and the Israelites

The Old Testament focuses on a family that became a nation. These were the Israelites, the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. The term Israelite is straightforward. The Angel of the Lord renamed Jacob after wrestling with him (Genesis 32:28). Jacob’s new name was Israel, which means “he strives with God.” Israel’s (Jacob’s) descendants became known as Israelites.

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

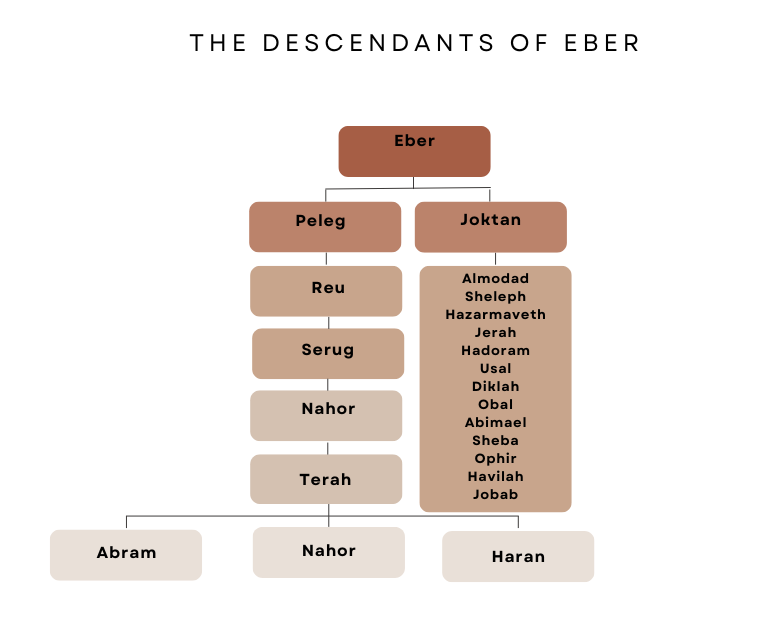

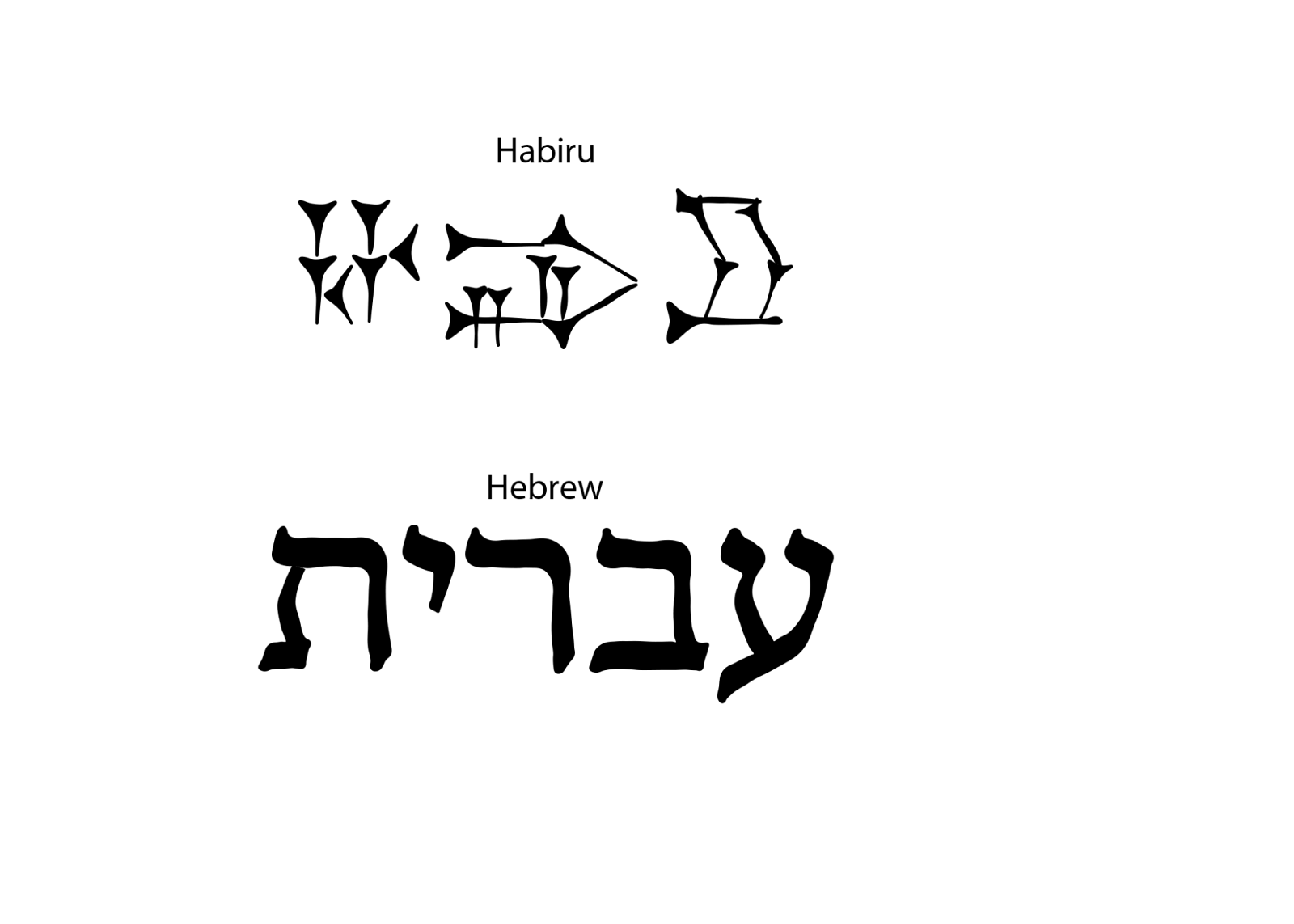

The Bible uses another term to describe this same group of people. It calls them Hebrews. Generally, we might think of the word Hebrew as being interchangeable with the word Israelite, especially since Jewish people speak the Hebrew language. However, in Genesis 14:13 even before the Israelites existed, the Bible called Abraham a Hebrew. This suggests that the Israelites were part of a broader group of people, known as Hebrews, who existed before the Israelites did.

The word Hebrew has a linguistic connection with the name Eber. It literally means Eberite or descendant of Eber. Genesis 10:24 records the birth of Eber, who was one of Abraham’s ancestors. So, when the Bible calls Abraham a Hebrew, it could be saying that he is a descendant of Eber.

Hebrews Outside the Bible?

Centuries later, when Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt, the term Hebrew had a strong association with the Israelites. By this point, the Bible uses Israelite and Hebrew almost interchangeably (cf. Exodus 9:1; 35). But, even then, the Israelite Hebrews may have been part of a broader people group.

If the Hebrews were indeed a well-known people group in the Ancient Near East, it is possible that ancient texts other than the Bible might reference them.

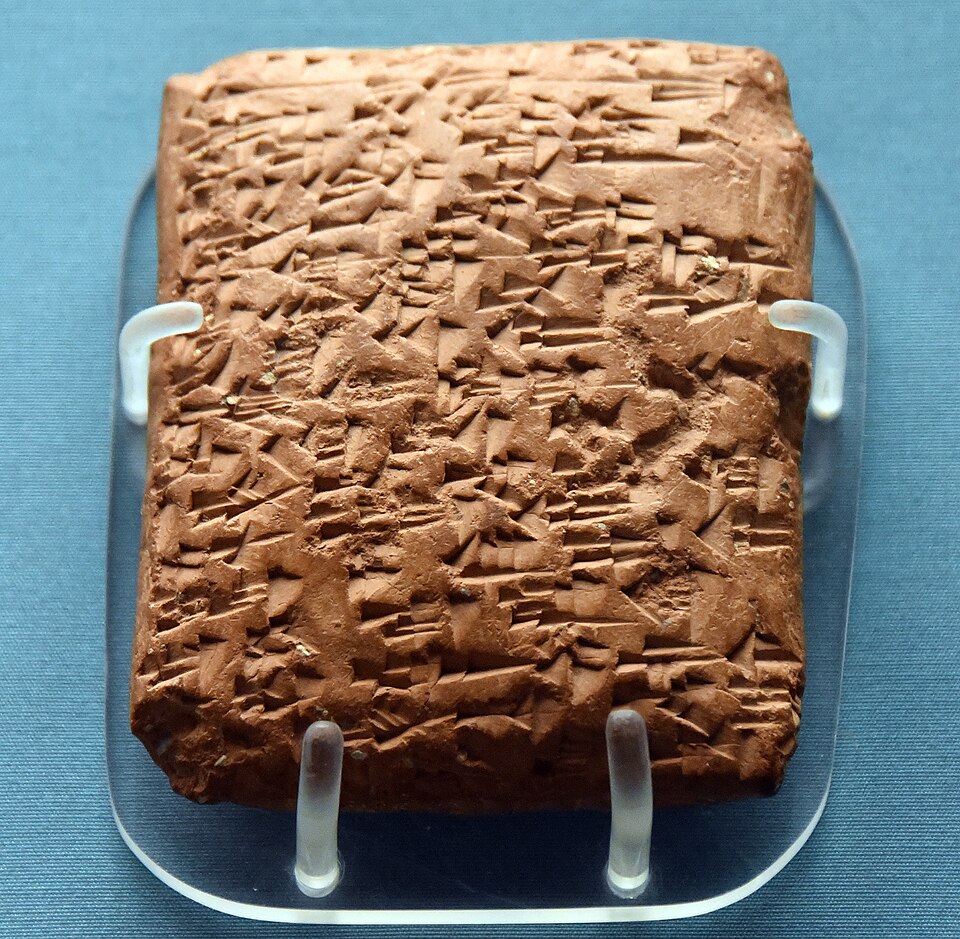

The Amarna Letters are a collection of ancient Near Eastern texts written in the Akkadian language.1 They refer to a group of people called the Habiru. The term Habiru does not seem to be an ethnic designation. Rather it refers to people who practiced a nomadic pastoral lifestyle. The Habiru were on the fringes of society and were sometimes seen as outlaws or bandits.2

There is a strong linguistic similarity between the words Hebrew (in the Hebrew language) and Habiru (in the Akkadian language). However, it is uncertain whether all of the Habiru were Israelite Hebrews. Rather, the Israelite Hebrews may have been part of the broader people group known as the Habiru. But, if the Habiru in the Amarna Letters equate to the biblical group of people known as Hebrews, could the Amarna Letters talk specifically about the Israelite Hebrews?

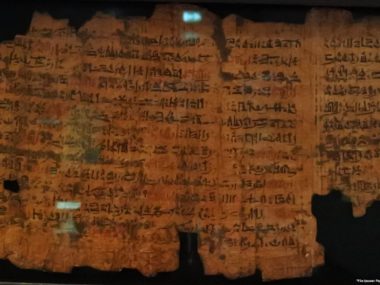

What are the Amarna Letters?

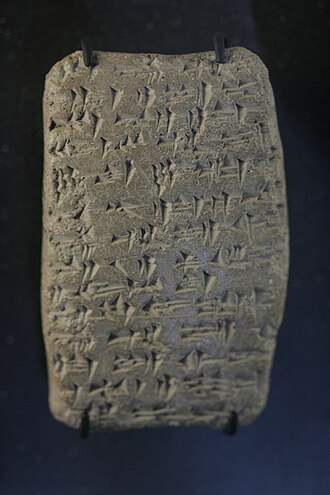

The Amarna Letters are clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform writing. Cuneiform, which means wedge-shaped, is a type of writing that was common in ancient Mesopotamia. Multiple cultures used cuneiform to write in their own languages. The Amarna letters were written in the Akkadian language with cuneiform letters.

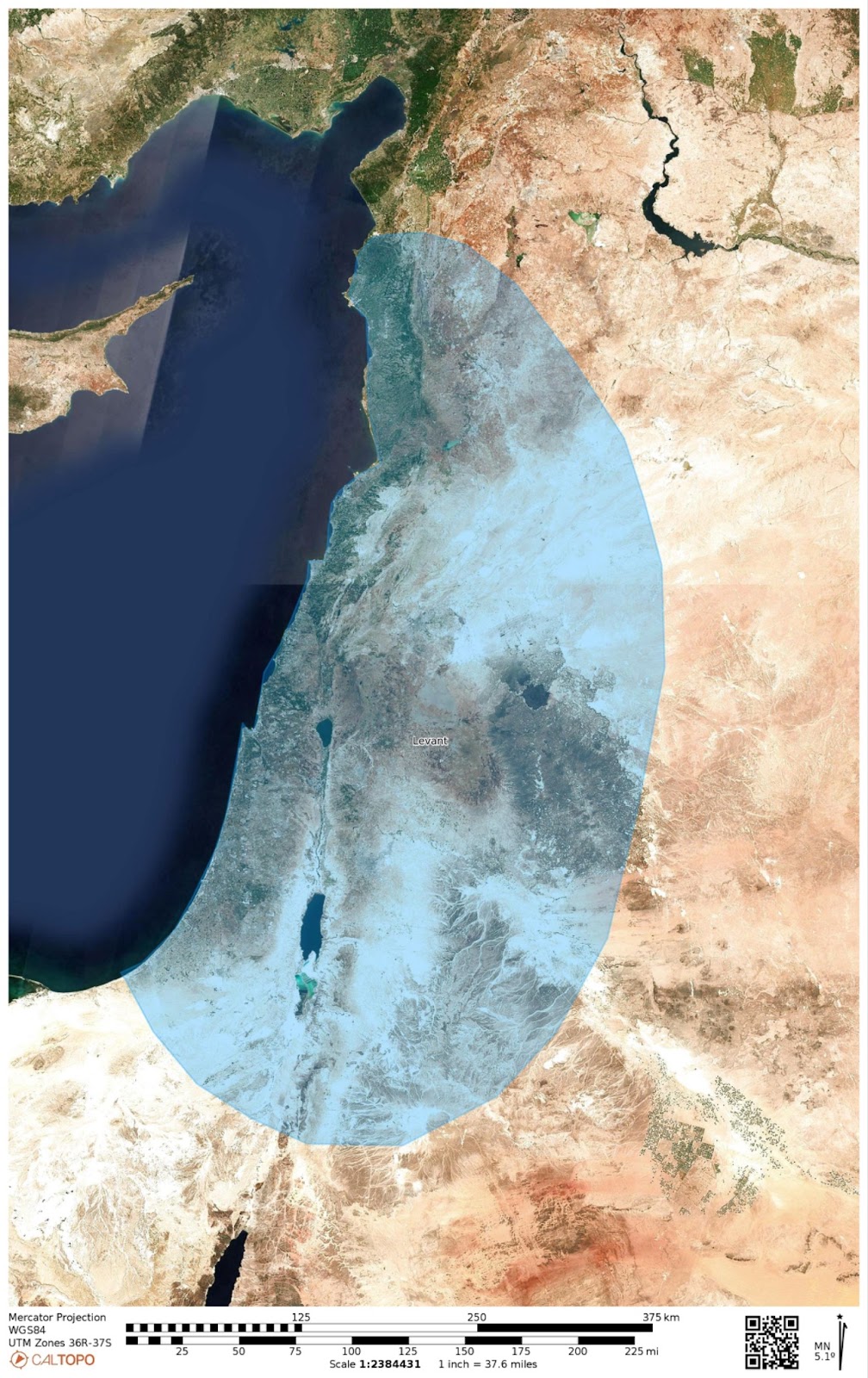

The Amarna letters were written by various city state rulers and in the Levant. The Levant is a region that includes modern day Israel and Lebanon. The recipient of the Amarna letters was the Pharaoh of Egypt. The letters were found in el-Amarna, Egypt.

El-Amarna, then known as Akhetaten, was a capital city founded by Pharaoh Akhenaten. The Amarna letters date to a narrow window of time from about 1360–1330 BC. Some were written to Pharaoh Amenhotep III and others to his successor, Akhenaten.

The authors of the Amarna letters ruled city-states in the Levant that were under the control of Egypt. This meant that they were required to pay taxes to Egypt. In return, they expected Egypt to protect them from their enemies.

Matching the Timeline

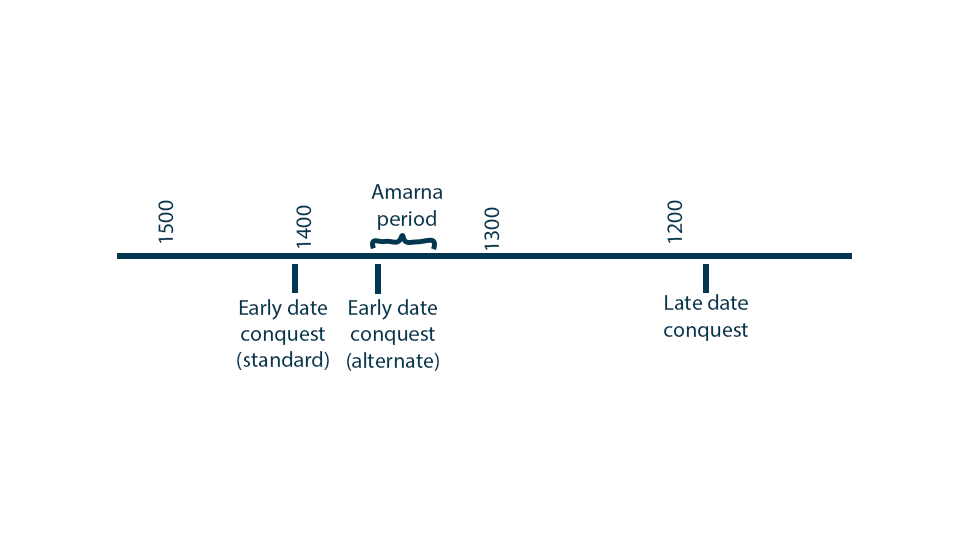

In order to compare the Habiru of the Amarna Letters with the Israelite Hebrews, it is necessary to discover where the date of the Amarna Letters lands on the biblical timeline. The Amarna Letters date to the mid-fourteenth century BC (1360–1330 BC). Biblical scholars are divided on the status of the Israelites during that timeframe. For more information on the difference in dating schemes, see this article.

Those who hold to a late-date Exodus believe that the Israelites were slaves in Egypt during the fourteenth century BC. Thus, according to that view, the Habiru in the land of Canaan cannot be the Israelite Hebrews.

For those who hold to an early-date Exodus, however, it is possible that the Habiru might be the Israelite Hebrews. The standard early-date Exodus places the beginning of the conquest at 1406 BC. In this scenario, the earliest Amarna Letters were written about 35 years after the Conquest began. Thus, they could discuss a later phase of the Conquest.

The alternate early-date Exodus works best with the Amarna Letters. This dating scheme, following the Septuagint text, places the beginning of the conquest around 1366, right when the Amarna Letters were being written. Thus, if this view of the Exodus is correct, the Amarna Letters describe the Israelite Conquest of Canaan, presenting the same events from a different perspective than the Bible.

The Habiru and the Hebrews

Let’s compare the Amarna Letters with the books of Joshua and Judges to see how the accounts match.

The Hebrews as Nomads

According to Genesis 47:3, the Israelites were shepherds by trade. In the ancient near east, shepherds were nomadic people, moving seasonally to different grazing areas. For example, when Joseph went in search of his brothers, he went north to Shechem to look for them, but was told that they had moved even further north, to Dothan (Genesis 37:14, 17).

Later, after the Israelites left Egypt, they wandered in the wilderness 40 years before entering the promised land. During this time, they lived in tents rather than in permanent structures. Thus, when the Israelites entered Canaan, the locals would have viewed them as nomads and outsiders.

The Habiru as Nomads

The Amarna Letters portray the Habiru as social outcasts or outsiders from society. For example, Amarna Letter (EA) 67 likens the Habiru to stray dogs.

EA 67: “Now he (Aziru) is like the Habiru man, a stray dog. – Author unknown.3

Another letter, EA 77, describes the Habiru as foreigners and dogs.

EA 77: “Now, why have you kept silent concerning the foreigner, the dog, who is attacking the territories? Won’t you speak to your lord that he send you at the head of the regular troops that you might drive off the Habiru men from the city rulers?” – Rib-Addi, ruler of Byblos.

The Hebrew Conquest

The book of Joshua describes the Israelite conquest of Canaan. Joshua 11:16–17 summarizes the initial conquest:

“So Joshua took all that land the hill country and all the Negeb and all the land of Goshen and the lowland and the Arabah and the hill country of Israel and its lowland from Mount Halak, which rises toward Seir, as far as Baal-gad in the Valley of Lebanon below Mount Hermon. And he captured all their kings and struck them and put them to death.”

The Habiru Conquest

Similarly, the Amarna Letters describe the Habiru taking over the land. Here are some examples.

EA 274: “May the king, my lord, rescue his land from the hand of the Habiru men lest it be lost.” – Ba-Lat-Nese.

EA 307: “Now I am guarding the city of the king which is in my charge and may my lord be apprised that the Habiru men are strong against us so may the king be apprised concerning his land.” – Author unknown.

EA 286: “The king has no lands! The Habiru men have plundered all the lands of the king.” – Abdi-Heba, ruler of Jerusalem.

EA 299: “Now the Habiru men are stronger than we, so may the king, my lord, send forth his hand to me and may he deliver me from the hand of the Habiru men lest the Habiru men wipe us out.” – Lapahi, ruler of Gezer.

Amarna Letter 299 finds a close parallel with Joshua 10:33, which describes the Israelites wiping out the men of Gezer.

Joshua 10:33: “Then Horam king of Gezer came up to help Lachish. And Joshua struck him and his people, until he left none remaining.”

“Cities Which You Did Not Build”

In Deuteronomy 6:10–11, God promised the Israelites large and beautiful cities which they did not build, houses filled with good things, and vineyards and olive groves which they did not plant.

In the Amarna Letters, the Canaanites complain to Pharaoh about the Habiru taking over their towns.

EA 118: “Behold, if the yeoman farmers depart, the Habiru men will take the city. – Rub-Hadda, ruler of Biblos

EA 288: “But now the Habiru men are taking the cities of the king. There is not one city ruler left to the king, my lord. All are lost!” – Abdi-Heba, ruler of Jerusalem.

Treaties with the Locals

In some cases, the Israelites made treaties with locals, such as in the case of the Gibeonites (Joshua 9:3–15). The same situation appears in the Amarna Letters. Compare Amarna Letter 289, written by the ruler of Jerusalem, with Joshua 10:1–2.

EA 289: “So may the king take thought and may the king send fifty garrison troops to protect his land. All the land of the king has deserted.” – Abdi-Heba, ruler of Jerusalem.

Joshua 10:1–2: “As soon as Adoni-zedek, king of Jerusalem, heard how Joshua had captured Ai and had devoted it to destruction, doing to Ai and its king as he had done to Jericho and its king, and how the inhabitants of Gibeon had made peace with Israel and were among them, he feared greatly, because Gibeon was a great city, like one of the royal cities, and because it was greater than Ai, and all its men were warriors.”

Shechem’s Alliance with the Habiru

In the Amarna Letters, there seems to be a particularly strong tie between the city of Shechem and the Habiru. However, it is unclear whether the mayor himself is consorting with the Habiru, or if only his sons are. It appears that they gave both silver and land to the Habiru.

EA 246: “And now the two sons of Lab’ayu are giving their silver to the Habiru men and to the men of the land of the Sutu to make war against me.” – Biridiya, mayor of Megiddo

EA 287: “Look, this deed is the deed of Milkili and the deed of the sons of Lab’ayu, that they have given over the land of the king to the Habiru men.” – Abdi-Heba, mayor of Jerusalem

EA 254: “Furthermore, concerning my son the king has written. I did not know that my son has been associating with the Habiru, but behold, have I not turned him over to Addaya?” – Lab’ayu, mayor of Shechem

EA 289: Look, the territory of the city of Gath-carmel belongs to Tagi and the men of Gath are the garrison in Beth-shean. ‘So let us do like Lab’ayu!’ And they have given the territory of Shechem to the Habiru men!” – Abdi-Heba, mayor of Jerusalem

The Bible does not specify that the Israelites made any kind of treaty with the Shechemites. However, it is interesting to note that they apparently moved into Shechem without a fight and held religious ceremonies there (Joshua 8:33; 24:1).

Additionally, Joshua 24:32 notes that Joseph was buried at Shechem in a plot of ground belonging to Jacob. It is possible that there was a historical memory of Jacob owning land at Shechem, and even conquering the City of Shechem (Genesis 34:25–29). There may have been an understanding between the Israelites and the Shechemites based on Jacob’s history with the city.

Chariots in the Valley

After the initial conquest, Joshua sent out the tribes to conquer their individual areas. Unfortunately, the tribes did not do a good job of finishing the conquest. For example, some of the Israelites complained to Joshua about being forced into the mountains because the Canaanites in the valleys have chariots.

Joshua 17:16: “The people of Joseph said, ‘The hill country is not enough for us. Yet all the Canaanites who dwell in the plain have chariots of iron, both those in Beth-Shean and those in the Valley of Jezreel.’”

In a very close parallel to this passage, Biridiya, ruler of Megiddo wrote Amarna Letter 243 to Pharaoh telling him about how he is guarding the city with chariots.

EA 243: “I am guarding the city of Megiddo, the city of the king, my lord, day and night. By day I am guarding from the open fields in chariots and by night I am guarding the walls of the city of the king my lord. But now the hostility of the Habiru men is tense in the land.” – Biridiya, ruler of Megiddo.

The city of Megiddo lies in the Valley of Jezreel, one of the very places mentioned in Joshua 17:16.

Hivites in the North

Judges 3:1–3 lists nations that the Israelites were not able to conquer, including the Hivites, who lived in the mountains of Lebanon, as far north as Hamath. Hamath lies on the Orontes River just north of Kadesh.

According to EA 189, the ruler of Kadesh successfully defended his city against the Habiru:

EA 189: “But I came and your deity and your sun god were going before me and I returned the cities to the king, my lord, from the Habiru men in order to serve you. So I expelled the Habiru men.” – Etakkama, ruler of Kadesh.

Conclusion

The similarities between the Israelite Conquest in Joshua and Judges and the Habiru takeover of Canaan in the Amarna Letters are remarkable. If the Habiru of the Amarna Letters are indeed the Hebrews of the Bible, then the Amarna Letters provide a compelling parallel to the books of Joshua and Judges.

More work is needed in comparing the Amarna Letters with the Bible. In particular, it is important to work out the timeline. The Amarna Letters seem to fit best with the alternate early-date Exodus, but this dating scheme is not widely accepted, and much work is needed to see how it fits within the broad corpus of historical, archaeological, and textual data.

Footnotes

1. Cohen, Raymond. 1996. “On Diplomacy in the Ancient Near East: The Amarna Letters.” Diplomacy and Statecraft 7:2, 245–270.

2. Waterhouse, S. Douglas. 2001. “Who Are the Habiru of the Amarna Letters?” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society 21:1, 31–42.

3. All quotes from the Amarna Letters are from: Rainey, Anson F. 2015. The El-Amarna Correspondence: A New Edition of the Cuneiform Letters from the Site of El-Amarna based on Collations of all Extant Tablets. Volume 1. Leiden and Boston: Brill.