Who makes it rain? Today, we understand concepts such as evaporation, condensation, and precipitation. Weather is a natural process. But, even though we understand the mechanics of the process, most Christians believe that God set these systems in place to sustain the earth. He promised, “While the earth remains, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, winter and summer, and day and night shall not cease.” (Genesis 8:22). Jesus stated that the Father “sends rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:45).

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author mentioned, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

The First Rainstorm

The first rainstorm mentioned in the Bible was a big one – it flooded the whole world! Rain from the heavens combined with water underground to cover the earth with water. It was very clear who made it rain. God predicted it in advance: “I Myself am bringing floodwaters on the earth, to destroy from under heaven all flesh in which is the breath of life” (Genesis 6:17). Yet, people were quick to invent gods and credit them with the great flood, and even with storms in general.

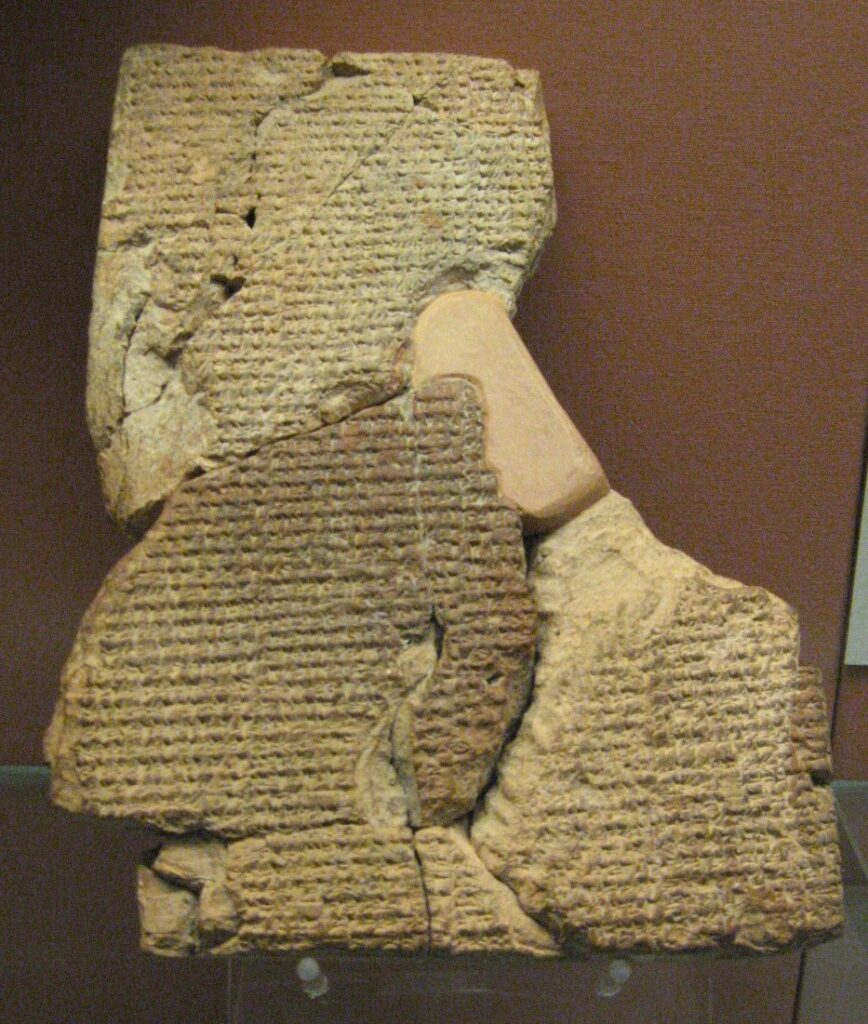

The Adventures of Enki and Atrahasis

Enki was an early Sumerian god of water. The temple to Enki in ancient Eridu is the oldest known temple in that region. The Sumerians credited Enki with a variety of accomplishments in stories that parallel those of Creation, Noah’s Flood, and the Tower of Babel. These events appear in The Epic of Atrahasis1 and Enmerker and the Lord of Aratta.2

The Creation of Humans

According to The Epic of Atrahasis, the creation of humans came about when the lower gods could not keep up with their work of building canals. They surrounded the house of the great warrior-god Ellil and announced,

“Every single one of us gods declared war! We have put a stop to the digging. The load is excessive, it is killing us! Our work is too hard, the trouble is too much! So every single one of us gods has agreed to complain to Ellil.”

Ellil’s advisors suggested creating humans as laborers to lessen the work of the gods. They decided Enki was the right god for the job, and he agreed to make humans out of clay mixed with the flesh and blood of one of the lesser gods, whom they would kill for this purpose.

All went as planned, and the humans performed their role as canal-builders. But as the population grew, the people became noisy, “as noisy as a bellowing bull.” Ellil was annoyed, and told the gods, “The noise of mankind has become too much, I am losing sleep over their racket.” So, Ellil gave the command to send a disease to decimate the human population.

The Great Flood

Then, Atrahasis, the human hero of the story, enters the scene.

“Now there was one Atrahasis whose ear was open to his god, Enki. He would speak with his god and his god would speak with him.”

Atrahasis complained to Enki about the spreading disease, and Enki instructed him on how to stop the disease. But again and again, the people became too noisy. Ellil tried multiple methods of wiping them out – famine, lack of oxygen, and illness. But, again and again, Atrahasis, with the help of his god Enki, outwitted him.

Then, Ellil concocted a new plan. Enki, the water god, could create a flood to wipe out the humans. Enki protested,

“Why should I use my power against my people? The flood that you mention, what is it? I don’t even know! Could I give birth to a flood? That is Ellil’s kind of work!”

But Enki could not stop the plans to flood the earth. Instead, he warned Atrahasis, “Dismantle the house, build a boat, reject possessions, and save living things… I shall make the rain fall on you here.”

Atrahasis then spoke to the elders of the people and explained the situation. Everybody pitched in to help build the boat. Atrahasis loaded the boat with animals, birds, and his family members. The floodwaters came, but Atrahasis and his family rode out the storm.

However, it wasn’t long before Ellil noticed the boat. He was furious, and reminded the gods,

“We the Anunna, all of us together, agreed together on an oath! No life form should have escaped! How did any man survive the catastrophe?”

One of the other gods knew the answer. “Who but Enki would do this?”

Enki quickly took credit for his work. “I did it in defiance of you! I made sure life was preserved.”

The Problem of Languages

In another Sumerian epic, Enmerker and the Lord of Aratta,3 Enki changed the languages of the people, apparently uniting them.

“The whole universe, the well-guarded people – may they all address Enlil together in a single language! For at that time, … for the ambitious lords, for the ambitious princes, for the ambitious kings, Enki the lord of abundance and of steadfast decisions, the wise and knowing lord of the land, the expert of the gods, chosen for wisdom, the lord of Eridug, shall change the speech in their mouths, as many as he had placed there, and so the speech of mankind is truly one.”

The Sumerian Myths versus Genesis

The details of the stories differ significantly from those of the biblical narrative. Enki interacts with other gods, who have less than exemplary behaviors and motivations. Humans are created simply to do work that the gods do not want to do. Their creation also requires the death of a god. The flood is a culmination of failed attempts by the gods to wipe out mankind. Meanwhile, Enki, the god who created mankind, works against the other gods to save his creatures. The narrative of Enki uniting the languages of the people is reminiscent, but opposite, of God confusing the languages at the Tower of Babel.

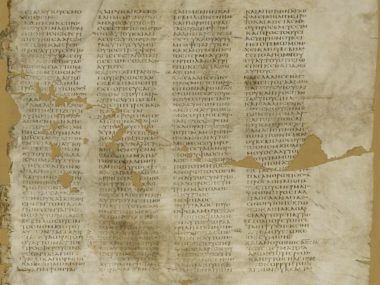

Yet the underlying themes of the stories seem to parallel those in the biblical text. Many scholars assume that the biblical writers were familiar with the Sumerian legends. They suggest that the early chapters of Genesis are an invented version of the old myths. Yet, perhaps instead, the similarities between Genesis and the Sumerian myths reflect the fact that these events actually occurred and that both the writer of Genesis and the Sumerian writers knew of these events.

The Storm Gods of the World

As people spread out over the earth, they developed different systems of worship, and different gods to worship. Yet, the various cultures tended to have similar pantheons of gods.

Prominent among these gods was the storm god. Rain represented fertility. Without rain, the crops would not grow. Animals would die. People would go thirsty. And so, the people believed it was important to pray and sacrifice to the storm god, asking him to send rain. Storm gods were also often associated with war.

Each culture, sometimes even each city, had its own storm god, responsible for the local weather. In Egypt, Horus was one of the most prominent gods. He was the god of the sky, the weather, storms, and war. The Amorite god, Adad, was responsible for rain, fertility, and storms. Wer was another weather god, of ancient Mesopotamian. The Greek god Zeus was the king of the gods, responsible for the weather and the sky. Jupiter was the Roman equivalent of Zeus.

Cultures worldwide had storm gods. Some still worship these gods today. In Norse legends, Thor was the god responsible for lightning, thunder, storms, and fertility. In Hinduism, Indra is the god responsible for the sky, storms, rain, and war. Yu Shi is the Chinese god of rain, and Raijin is the Japanese god of thunder, lightning, and storms.

Baal, the Canaanite Storm God

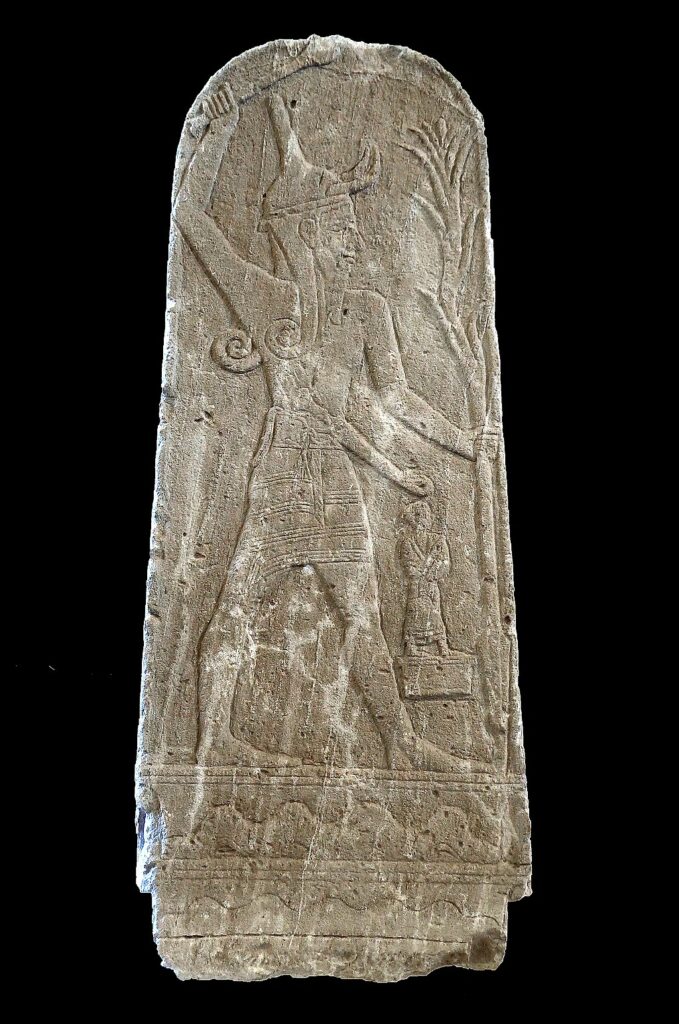

But of all the storm gods, Baal is, perhaps, the most well-known, especially among Bible readers. Baal was the Canaanite storm god. The Baal Cycle,4 an Ugaritic text from the Late Bronze Age, tells the story of Baal’s dealings with other Canaanite gods. The story focuses on Baal’s battles with the sea god, Yamm, and the god of death, Mot. In the end, Baal triumphs over both of his enemies.

Depictions of Baal sometimes show him as a man, and sometimes a bull. He usually brandishes weapons. Sometimes Baal holds a raised mace, a weapon consisting of a handle with a club head. Sometimes he brandishes a lightning bolt, symbolizing his control over thunderstorms.5

The Israelites, after their Exodus out of Egypt, encountered Baal worshippers even before they entered the promised land. The Moabites, who lived east of the Jordan River, worshiped Baal of Peor. The Moabite women seduced the Israelite men to worship Baal of Peor with them (Numbers 25:1–3). God punished the people for this, but throughout early Israelite history, the people dabbled with Baal worship time and again (Judges 2:13; 6:25; 8:33).

Finally, during the time of King Ahab, Baal worship became the official religion of the Kingdom of Israel (1 Kings 16:31–32). Ahab was a powerful and wealthy king. Archaeological excavations have revealed hundreds of beautifully carved ivory inlays that decorated his palace.6 Ahab married a Sidonian princess, Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal. The name Jezebel means “Baal carries,” and Ethbaal means “Baal is with him.”7 Thus, Ahab married into a family of Baal worshippers, and immediately set up an altar for Baal, built a temple for him, and worshiped him.

The First Challenge

In response to Ahab adopting Baal worship, the prophet Elijah declared, “As the LORD, God of Israel, lives, before whom I stand, there shall be neither dew nor rain these years, except by my word” (1 Kings 17:1). This edict was a direct challenge to the abilities of Baal. Baal was the storm god. By worshiping him, the people were expressing their belief that Baal was the god who made it rain. Elijah was essentially claiming that the Lord God of Israel was the God who made it rain.

The challenge had been issued. The people waited and continued to worship Baal. No rain came.

The Second Challenge

A few years passed. By now, there was a severe famine in the land. Crops were not growing, and people didn’t have enough food or water. Baal was not doing a very good job as a storm god. Now, Elijah issued a new challenge.

“How long will you go limping between two opinions? If the LORD is God, follow Him; but if Baal, then follow him.” And the people did not answer him a word. Then Elijah said to the people, “I, even I only, am left a prophet of the LORD, but Baal’s prophets are 450 men. Let two bulls be given to us, and let them choose one bull for themselves and cut it in pieces and lay it on the wood, but put no fire to it. And I will prepare the other bull and lay it on the wood and put no fire to it. And you call on the name of your god, and I will call upon the name of the LORD, and the God who answers by fire, He is God.” And all the people answered and said, “It is well spoken” (1 Kings 18:21–24).

Again, Elijah’s proposed contest was a direct challenge to Baal, the storm god. In addition to making it rain, Baal was responsible for lightning. Which god could send lightning from heaven to set fire to the offering? They were about to find out.

The Showdown

The prophets of Baal took the contest seriously. They did everything in their power to convince Baal to send fire from heaven. They cried out, danced around the altar, and cut themselves. But Baal did not respond.

Finally, Elijah prepared his offering, and just for good measure, he soaked the entire altar with water. Then, very simply, he prayed.

“Answer me, O LORD, answer me, that this people may know that you, O LORD, are God, and that you have turned their hearts back.” (1 Kings 18:37).

And promptly, fire came from heaven and burnt up not only the offered bull, but also the wood, the stone altar, the dust, and the water that Elijah had poured over it. God had proven Himself to be the ultimate Storm God, but He wasn’t finished yet. Before King Ahab made it home that day, God sent a heavy rainstorm. The drought was over. And it was very clear that the Lord God of Israel, and not Baal, was the God who made it rain.

“Are there any among the false gods of the nations that can bring rain? Or can the heavens give showers? Are you not he, O LORD our God? We set our hope on you, for you do all these things.” – Jeremiah 14:22

References:

- Dalley, Stephanie Mary. 1989. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G. 1998. The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford.

- See 2.

- Smith, Mark S. 1994. The Ugaritic Baal Cycle, Volume I: Introduction with Text, Translation and Commentary of KTU 1.1–1.2. Leiden, New York, and Koln: Brill.

- Töräänvuori, Joanna. 2012. “Weapons of the Storm God in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblial Traditions.” Studia Orientalia 112, 147–180.

- Suter, Claudia E. 2011. “Images, Tradition, and Meaning: The Samaria and Other Levantine Ivories of the Iron Age.” In A Common Cultural Heritage: Studies on Mesopotamia and the Biblical World in Honor of Barry L. Eichler. CDL Press

- Prutin, Dagmar. 2007. “What is in a Text? – Searching for Jezebel.” In Ahab Agonistes: The Rise and Fall of the Omride Dynasty, edited by Lester L. Grabbe, 208–230. New York: T&T Clark.

Thank you for the summary of godly power…looking for a power to bring rain to the parched lands.