Recently I was teaching my high school physics class, and I brought the students outside to do a simple experiment illustrating Newton’s First Law of Motion. To see the effect of inertia, the students had to run while dropping beanbags and compare the placement of the fallen beanbags to those that were just dropped from rest. I encouraged them to see how this simple experiment proved that Newton was correct and Aristotle was wrong about motion. At the end of the experiment, one of my students noted that this experiment was so simple, there was no way that the Greeks could have conducted experiments. I encouraged him by noting that he was correct, but it took Christendom to see why empiricism should be valued above rationalism in the natural world.

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author, and not necessarily those of New Creation.

History of the Scientific Method

Although many history books point to ancient Egyptians or Greek philosophers as the founders of scientific study, the logic of the scientific method was actually worked out during early Christendom. The science historian Alistair Crombie claims that the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century was distinct from ancient Greek philosophy because of “its conception of how to relate a theory to the observed facts it explained, the set of logical procedures it contained for constructing theories and for submitting them to experimental tests.”1 He goes on to describe the value that Plato put on deductive reasoning by explaining:

The basic doctrine, formulated by Plato and Aristotle and carried to its consequences by Euclid, was that science could be established deductively by starting from certain irreducible postulates, which could not themselves be proved by were grasped by intuition; they could not be overthrown or even modified or limited by any result of scientific investigation.2

Rather than the ancient Greeks, the history of the scientific method actually begins with Augustine. In his debates with the Greek Skeptics from Plato’s Academy, Augustine argued that inductive reasoning is just as valid as deductive reasoning. Contrary to Platonism, he argued that self-evident truths have value, proven by the fact that God uses both the revealed truth of Scripture and logical truth from reasoning. The Christian creeds echo this belief when they claim that God reveals Himself “in Word and in Nature.” In the 6th century, Boethius used Augustine’s argument in his commentaries on Greek philosophy to draw a distinction between knowledge gained by experience and knowledge gained by reason.3

After Aristotle was translated into Latin, a new interest in natural philosophy was sparked. In the 13th century, Robert Grosseteste, the bishop of Lincolnshire, explained his theory of natural philosophy in his commentary on Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics and Physics, the same textthat had been originally translated by Boethius. In his commentary, Grosseteste emphasized the distinction between experiential knowledge and rational knowledge, and used the example of mathematics to show that rather than deductive reasoning, experiential knowledge was actually the superior source for information about the natural world.4 He believed that natural philosophy should involve a combination of inductive and deductive reasoning, which he called “resolution and composition,” but it should be combined with verification and falsification by experiment. Grosseteste was the first to argue that logical deductions required empirical verification and falsification to verify a particular hypothesis, and that reasoning itself could not necessarily finalize truth. He believed that limited scientific claims could be shown by experiment, but that only Divine Inspiration could give absolute metaphysical certainty on truth.5

Grossteste also pointed out where Aristotle’s conclusions did not match observations, especially in the study of optics. He observed the wave nature of light and used observation and experiment to differentiate between the effects of reflection and refraction, even coming close to formulating the Law of Reflection. Grosseteste continued his work at Oxford until he was succeeded by his student Roger Bacon. Bacon went further than Grosseteste, and argued that in matters of natural philosophy, inductive reasoning is actually superior to the deductive:

The man without experience must not seek a reason in order that he may first understand, for he will never have this reason except after experiment…For if a man is without experience that a magnet attracts iron, and has not heard from others that it attracts, he will never discover this fact before an experiment.6

Bacon concluded that rather than support Aristotle, most of Grosseteste’s experimental observations had actually proven Aristotle wrong on the nature and behavior of light. He continued to build upon Grosseteste’s experiments, and expanded his studies from optics to the structure of the eye and how it sees light. In the generation after Bacon, Thomas Bradwardine used mathematics to model Bacon’s experiments. These mathematical models overturned Aristotle’s physics of motion and laid the groundwork that Isaac Newton would later use to invent Calculus.7

This Oxford School of natural philosophers laid the groundwork for the Scientific Revolution. Both Grosseteste and Bacon traveled to Paris on various occasions, teaching experimental science to natural philosophers on the continent. Grosseteste visited with scholars in Paris in 1209, while Bacon visited the philosopher Albertus Magnus in Cologne and in Paris. Albertus Magnus had also written commentaries on Aristotle’s works and insisted that proper science would test theories by experiment in order to determine causes and natural laws.

Alistair Crombie summarizes this moment in his history of science:

The truth seems to be that Oxford took the lead in a general movement in Western Christendom. The advances made in 13th and 14th century Paris, Italy, and the Germanies were to a large extent the result of an independent use of the Greek and Arabic sources as they became available in Latin. Yet Oxford’s lead in methodology enabled her to a considerable degree to dominate the conceptions of natural science forming in other, contemporary centers.8

The dismantling of Aristotelian science continued on the continent. Based on Grosseteste and Bacon’s astronomical observations, Pietro d’Abano, a natural philosopher at the university in Padua, Italy, suggested that the heavenly bodies did not exist in spheres, but moved about freely in space. He even suggested that “appearances could be saved” by considering that the earth moved, rather than the heavens. Two hundred years after Pietro d’Abano’s death, a student who had also studied at Padua, Nicholas Copernicus, began to hypothesize that d’Abano was correct.9

About 30 years after Copernicus passed away, another Paduan professor, Galileo Galilei, used his newly designed optical telescope to look into outer space. What he saw there provided a crucial counterexample to the theory of geocentrism, that Earth was the unmoving center of the universe. Galileo observed that moons orbited around Jupiter and that the planet Venus had phases, meaning that it orbited the Sun.10

Galileo’s experiments were famous throughout Europe, and news of them reached Francis Bacon in England. Although not related to Roger Bacon, Francis was also a natural philosopher and politician in the court of King James I. In 1620, shortly after Galileo published his telescopic observations, Francis Bacon published his work Novum Organum, in which he used Grosseteste’s experimental process to formally outline the steps of the scientific method including observation, hypothesis, experiment, and theory. Bacon fully parted with Greek philosophy by asserting that the scientific method’s process of discovering the natural world was rooted in inductive reasoning that came from empirical observation, rather than deductive reasoning like Greek philosophy. Francis Bacon explained how a counterexample provides an “exclusion” to a theory, meaning that science cannot prove causes, but can disprove causes. This is the fundamental principle of falsification first described by Robert Grosseteste.11

Isaac Newton fully broke with Aristotlean philosophy in his famous phrase “hypotheses non fingo.”12 By stating that he has no hypotheses, Newton was emphasizing that he comes to his scientific theories entirely by empirical methods, with no prior prejudices from reason. In Newton’s letters, he regularly referred to Augustine’s arguments about self-evident truth, and explained that mathematics was the tool that connected empirical evidence to rational knowledge. Benjamin Franklin was an avid reader of Newton’s work, and pulled from Newton’s argument for self-evident truths when he suggested that edit to Thomas Jefferson when he was writing the Declaration of Independence.13

It is not by coincidence that the Protestant Reformation also followed on the heels of the Scientific Revolution in the 16-17th centuries. One of Grosseteste’s clerical reforms at Oxford was to base his lectures on the text of the Bible, rather than on church tradition. Like Augustine, he valued self-evident truth from Scripture, which meant that he wanted congregants to hear the Word of God for themselves. In order to accomplish this, he instructed his friars to teach the Apostle’s Creed, the 10 Commandments, and the Lord’s Prayer to the laity. The Morning Star of the Reformation, John Wycliffe, lived 100 years after Robert Grosseteste and claimed that he was one of the greatest philosophers of the Western World. He used Grosseteste’s pattern of centering his teaching on Scripture, and used the common language as the basis of his own teaching in order to further educate the laity to find truth in the Scripture for themselves. Teaching in the vernacular continued to be a mark of the Protestant Reformation as William Tyndale, a century after Wycliffe, translated the Bible into English. Tyndale once stated in response to a learned man: “If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plow to know more of the Scripture than thou dost.”14

Darwinism is Falsified

The Scientific Revolution began when the scientific method falsified geocentrism, and continued on to the final undoing of Aristotle’s mechanics when Newton devised his Law of Universal Gravitation. In the 19th century, the tools of the scientific method were also applied to Darwinism. The same year that Origin of Species was published, Louis Pasteur set out to falsify the theory. Pasteur was a conservative Roman Catholic who understood Darwin’s implication that living organisms were makers of themselves.

He was, you see, a good Catholic….It was beginning to be the fashion of the doubters to believe in Evolution: the majestic poem that tells of life, starting as the formless stuff, steaming in a steamy ooze of a million years ago, unfolding in a stately procession of living beings until it gets to monkeys and at last–triumphantly–to men. There doesn’t have to be a God to start that parade or to run it–it just happened, said the new philosophers with an air of science.15

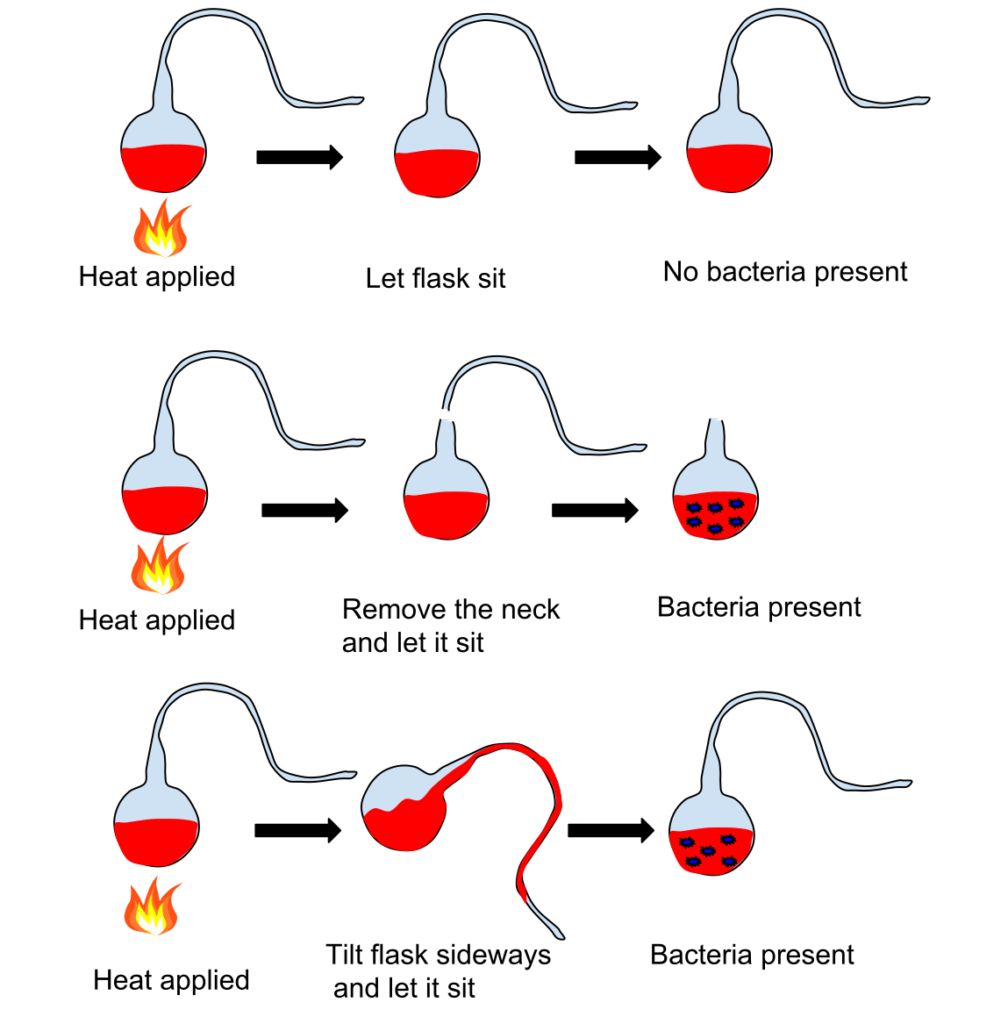

To falsify Darwin’s theory, Pasteur decided to take on another theory of Aristotle’s spontaneous generation. Aristotle had observed maggots growing on meat, and assumed that living organisms could arise from non-living organisms. After studying microorganisms, Pasteur presumed that this theory may be incorrect, so he designed an experiment whereby he boiled chicken broth and then let it sit out for days. After several days, he observed microorganisms growing in the broth. For his next step, Pasteur set up several pots of chicken broth in glassware that contained very narrow, winding stems. After boiling the broth, he tilted the glass so that some of the chicken broth was caught in a turn of the stem, closer to the open air. He did not do that to the other pot. Several days later, he observed microorganisms growing in the stem of the broth, but not in the broth in the glass, confirming that life was coming from outside the food and not arising from the food itself. Pasteur announced that by disproving spontaneous generation, Darwinism could not be true, since life cannot arise from non-living molecules.16

The next challenge to Darwinism was the discovery of the DNA molecule as the mechanism of inheritance. Darwin lived before the mechanism of inheritance was discovered, so his notion that observable small, incremental changes over time that organisms experience through adaptation could occur between any organisms on Earth was not an unreasonable idea. Darwin suggested that because adaptation can occur naturally within closely related species, then given enough time, change could occur between any species.

Unbeknownst to Darwin, his contemporary Gregor Mendel was a German monk who bred pea plants in his garden to discover the mechanism of inheritance in living organisms. Although his paper was largely forgotten when published, it was rediscovered in 1900 when scientists were attempting to determine the purpose of the DNA molecule. When scientists discovered that Mendel’s genes were actually present on the DNA molecule, the science of genetics was founded. The identification of DNA as the mechanism for inheritance was fully complete by 1953 when James Watson and Francis Crick published the structure of the DNA molecule.

The discovery of the mechanism of inheritance proved that the unlimited gene alterations required by Darwinism did not exist. No longer could a bacterium become a human being with slow changes over vast eons of time, because the information required to make a human being did not exist in the bacterium. Every trait an organism has is inherited by its parents, and any mutations of the genome create a loss of genetic information, rather than a gain. A great chasm opened up between Darwin’s theory of a common ancestor for all life, and what we now call microevolution, or adaptation. Just like Galileo’s observations provided a counterexample to geocentrism, the disproving of spontaneous generation and the discovery of DNA provided a counterexample to Darwinism.

The Return of Platonic Science

At this point scientists had the opportunity to denounce Darwinism, or to at least hold it as a highly contested theory. The 500-year-old scientific method that had brought about the Scientific Revolution had once again successfully used falsification and counterexample to disprove a popular theory. However, rather than acknowledge that doubt had fallen upon Darwinism, the scientific community largely decided to re-define science. Nine years after Watson and Crick discovered the structure of DNA, Thomas Kuhn published The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Returning to ancient Greek philosophy, Kuhn argued that empirical evidence is less important to the definition of science than the consensus of scientists. Without empirical evidence, the reigning paradigm becomes a religious devotion, as Kuhn describes the need to make “conversions.” He states, “the man who continues to resist after his whole profession has converted has ipso facto ceased to be a scientist.”17

As a result, much like Plato’s Republic, scientists become the philosopher-kings, whose job it is to control the paradigm by censoring any dissent. Darwinism can no longer be questioned because it is the consensus of scientists, and this return to consensus has fundamentally altered the study of science over the past 60 years. This is one of the reasons why creation scientists are so often met with mocking and scorn, rather than intelligent conversation. The empirical evidence of creationism cannot be discussed when creationists are no longer scientists. This has also entered the field of climatology where scientists are regularly censored or fired for any dissent of the environmentalist story. Even more recently, the Covid-19 debacle has shown what can happen when scientists form a consensus that is not allowed to be questioned, with the full backing of the state. This is why there have been no apologies or regrets about lockdowns, masks, or school shutdowns. Scientists can claim a change in the reigning paradigm, and if there’s no absolute truth, no unchangeable natural laws, then they can’t be held accountable to decisions made under a different paradigm.

A Way Forward

The development of empirical science is distinctly tied to the Christendom of the Middle Ages and over 1,000 years led to the Scientific Revolution. Without this heritage of medieval scientists, our modern world would not exist. Although primarily a way to study the natural world, the principles of empirical knowledge applied to government led to constitutional republics, and applied to theology led to the Protestant Reformation. It is not a coincidence that as the Western World has accepted Darwinism, it has also experienced a a loss of civic liberty and theological faithfulness. As long as scientists continue to remain faithful to Darwinism, despite evidence to the contrary, we are at risk of losing the heritage of the Scientific Revolution. Only a full repudiation of Darwinism will restore empiricism to scientific study.

Learn more about Liberal Arts, Darwinism & the Scientific Method

- Part I

Footnotes

- Crombie, Alistair, Robert Grosseteste and the Origins of Experimental Science, 1100-1700, Oxbow Books, 2002, 1. ↩︎

- Ibid., 7. ↩︎

- Ibid., 25. ↩︎

- Ibid., 46. ↩︎

- Ibid., 61. ↩︎

- Ibid., 142. ↩︎

- Ibid., 180. ↩︎

- Ibid., 189. ↩︎

- Ibid., 202. ↩︎

- Ibid., 297. ↩︎

- Ibid., 302. ↩︎

- Newton, Isaac, Principia, Cohen and Whitman, 1726, 943. ↩︎

- Franklin, Benjamin, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Yale University Press & American Philosophical Society, v. 23, 1979, 174. ↩︎

- Wycliffe, John, On Civil Lordship, 1376. ↩︎

- De Kruif, Paul, Microbe Hunters, Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1926, 78-79. ↩︎

- Ibid., 88. ↩︎

- Kuhn, Thomas, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, University of Chicago Press, 2012, 158. ↩︎