If you travel to Australia, you probably expect to encounter kangaroos, boomerangs, and didgeridoos. If you like natural wonders, you may even stop at ancient landmarks, such as Ayers Rock or the Great Barrier Reef. But if you explore Shark Bay in Western Australia, you will come across strange, lumpy rocks in the shallows. Except, these are not actually rocks. They are mounds of sediment constructed not by wind or waves, but by tiny microorganisms. And they also represent the oldest form of life on the planet. We call these microbial marvels stromatolites.

What are Stromatolites?

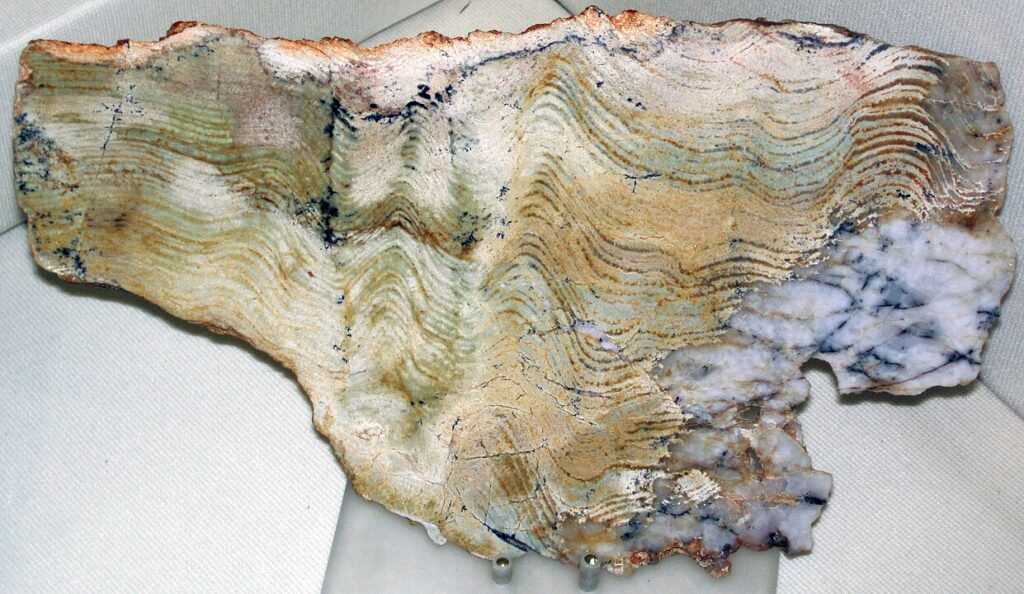

Stromatolites are a type of naturally-formed structure made from layered sediments and formed from communities of tiny microorganisms, such as bacteria and archaea. They belong to a group of similar structures called microbialites, of which there are three types. First are stromatolites, the primary focus of this article. These are domed or column-shaped structures made up of thin layers. They can range in size from wrinkled mats little more than a few centimeters thick to giant domed structures reaching a meter or more in height. Fossil varieties got far larger than modern ones, with some towering more than 20 feet tall! Thrombolites are also domed or column-shaped structures, but they are not composed of layers. And finally, we have dendrolites, characterized by branching structures that have layers.

Microscopic Construction Workers

Microbes are construction workers, but only by happenstance. When microbes live as a community on the bottom of a body of water, they form a sticky mat called a biofilm. Tiny grains of sediment floating in the water stick on the biofilm, forming a layer. These microbes need sunlight in order to grow. So the community moves up through the sediment and creates a new biofilm overtop of it. More grains of sediment accumulate to form a new layer and the cycle continues. Eventually, this forms a microbialite. When a large number of stromatolites form in the same general area, they can form a microbial reef. Picture Australia’s offshore Great Barrier Reef, but made out of giant mounds made by tiny microorganisms!

Due to the processes required for forming one layer at a time, it can take a long time for stromatolites to grow. The exact rate depends on the surrounding environment, with stromatolites growing fastest in shallow, salty water of high temperature. Growth rates can vary from 5 mm/yr to as much as 36 mm/yr.1,2 Those growing in favorable conditions can form a singular 1-millimeter layer per day.3 When researchers in Yellowstone National Park grew a silicon microbialite in a pond from scratch, they observed a 5.7 cm/yr growth rate.4 But many fossilized stromatolites are estimated to have grown even faster, often at a rate of 37 cm to 60 cm/yr.5

Living Among Us

Living populations of stromatolites are rare sights in the modern world. They often reside in environments that are inhospitable to other forms of life, like geothermal pools and lakes. Sometimes, we find them in cool, freshwater lakes, creeks, streams, and wetlands. Two spectacular places to see stromatolites in their natural environment are the aforementioned Shark Bay, off the coast of Western Australia, and Highbourne Cay, in the Bahamas. At both locations, there is plenty of warm, salty, and sunlit water for them to grow in. Modern stromatolites are quite small, typically measuring no more than three feet tall. Study of living microbialite communities can give scientists an idea of what their fossil counterparts may have been like when alive.

Fossil History

While rare in the present, stromatolites are the exact opposite in the fossil record. We can find them in the Archean, earth’s oldest rocks, all the way up until recent times. This makes them the oldest fossils known to science! One site, the Strelley Pool Chert in Western Australia, boasts a 10-meter thick vertical sequence of stromatolite-bearing layers that stretch 10 km across.6

Stromatolite abundance reaches an all-time high in Proterozoic rocks, which are directly above Archean rocks in the geologic column.7 These can get quite large, some measuring over eight feet tall! Geologists Andrew Snelling and Kurt Wise have studied some of these monster stromatolites in the Beck Spring Formation, which is exposed in the East Mojave in Nevada and Grand Canyon.8 Interestingly, this spike in microbialite abundance coincides with evidence for an increase in atmospheric oxygen content in the geologic record. We call this the Great Oxidation Event.

Ascending from the Proterozoic into the lower Paleozoic layers of the geologic column, we find a similarly high number of stromatolites. Unfortunately, they appear to go into a steady decline throughout the rest of the Paleozoic, before going through a brief last hoorah in the lower Triassic.9 Stromatolites never completely disappear (as they are still with us today) but they are rather small and rare, often getting no more than a few meters thick and only occurring in a few successive rock layers.

A Place on the Biblical Timeline

Given the prevalence of stromatolites throughout the fossil record, it is imperative that young-earth geologists determine their place in the timeline of earth history. A proper understanding of these microbial marvels can give us important clues into the types of environments in which geologic formations formed. For our purposes, we will peruse young-earth creationist research on stromatolites from four main periods of earth history: Creation Week, the pre-Flood world, the Flood, and the post-Flood world.

Creation Week

Most young-earth geologists regard the vast majority of the geologic record as having formed during Creation Week. We call this portion of the geologic column the “Precambrian.” It is composed of the Archean and most Proterozoic rock layers mentioned earlier. Therefore, most stromatolites present in the Precambrian would have been made during Creation Week as well. But if supernatural creation events characterize Creation Week, what can microbialite fossils teach us about the environments in which they formed?

Geologist Ken Coulson suggests that the geological events of Creation Week occurred in a time lapse fashion. He thinks processes happened at the same rates relative to each other. As such, environmental conditions we think were preserved in Precambrian rocks might still give us an idea about how the earth’s surface formed over this (brief) period of time.10 Geologists Andrew Snelling and Harry Dickens have argued that Archean rocks formed on Day 1 of Creation Week. Thus, they propose the stromatolites in these layers were likely specially created. On Day 2, Proterozoic rocks formed, and with them, layer upon layer of microbialite populations.11 Coulson suggests that these stromatolites served a temporary purpose in oxygenating the atmosphere, thus triggering the Great Oxidation Event.

The Pre-Flood World

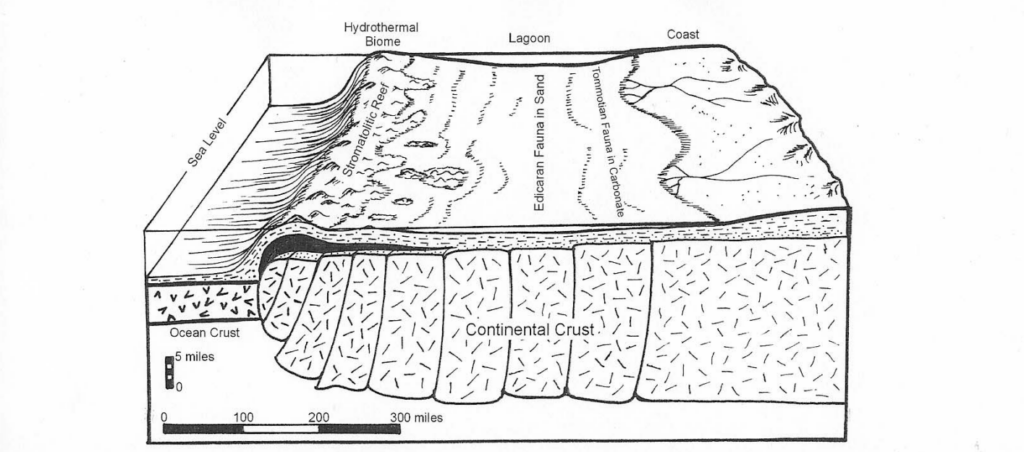

From his research on the giant stromatolites in the East Mojave and Grand Canyon region, paleontologist Kurt Wise has proposed that they formed the foundation of a salty, hot water reef that existed before the Flood, called the hydrothermal reef biome.12 According to his model, this reef existed along the continental shelf of the pre-Flood supercontinent(s?), spanning hundreds of miles wide. The type of sedimentary rocks in which these stromatolites are preserved suggests they lived in warm, salty water expelled from springs on the seafloor, similar to hydrothermal vents on the deep seafloor today. Wise thinks that the reef enclosed a wide, shallow lagoon that protected a great variety of shallow sea creatures.

The Pre-Flood/Flood Boundary

You may recall that stromatolites have a very slow growth rate. This makes it unlikely for many successive layers of large ones to have formed during the Flood year, even allowing for favorable environmental conditions. Their presence in the fossil record has raised questions as to which portions of it formed during the Flood.

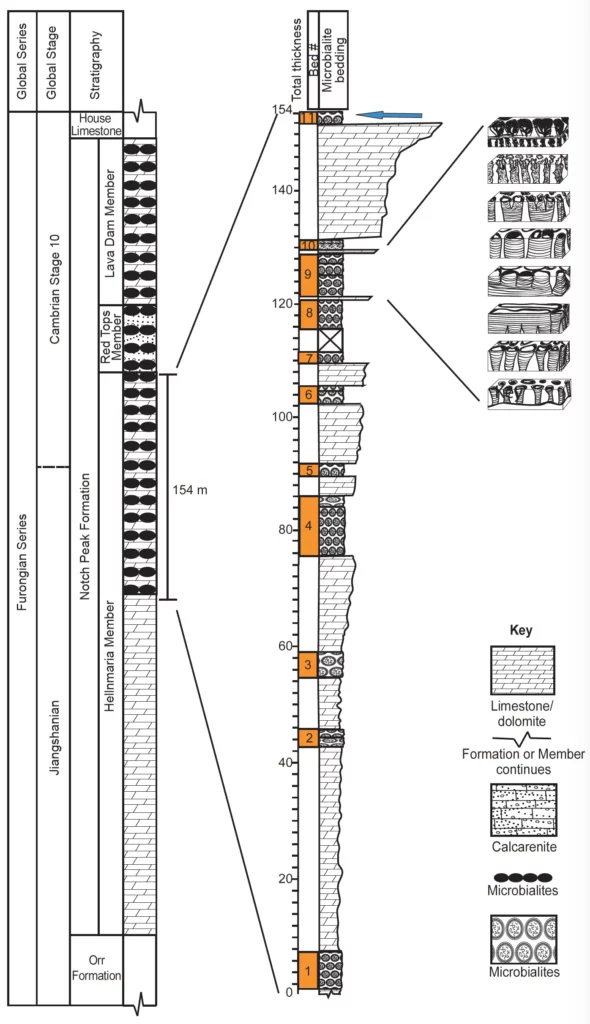

While still an active area of research, Coulson proposes that lower Paleozoic stromatolites formed in the pre-Flood era.15 His research is based on a site in western Utah within the Notch Peak Formation. This site consists of a 550-meter thick, vertical sequence of stromatolites. Coulson thinks these stromatolites inhabited a high-energy, shallow marine environment that was home to a variety of seafloor-dwelling organisms.

The layers in which these stromatolites occur have traditionally been considered some of the earliest formed during the Flood. However, the presence of a vertical sequence of stromatolites and how long they take to grow have caused some young-earth geologists, including Coulson, to reconsider this interpretation.

While stromatolites do occur throughout the fossil record, most of the post-Paleozoic examples are no more than a few meters thick. They also only occur at a few successive levels at a time. Coulson suggests that these smaller examples could have formed during the Flood.

The Post-Flood World

The Green River Formation is a series of geologic formations formed in what were once a series of intermountain basinal deposits along the border of Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado. Fossils of stromatolites are common at multiple sediment layer levels along the edges of these basins. The stromatolites and other microbial growths along the edge of the Green River Formation basins form complex reef-like structures. Some of these measure up to nine meters tall and 40 meters in diameter.

Stromatolitic reef-like structures such as this are unlikely to form over the course of a few months during the Flood. This, combined with other geologic and fossil evidence, has led a number of young-earth geologists to suggest that the Green River Formation formed well after the Flood.16 Within the years or decades after the floodwaters receded, large lakes formed in the intermountain basins in Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado. Stromatolites made homes for themselves along the edges of these lakes.

Conclusion

At first glance, stromatolites look like boring, lumpy rocks. They are anything but! These microbial marvels, both living and fossil, offer us incredible insight into the past. Careful study of stromatolites allows us to reconstruct what ancient environments may have been like. It also gives us a better understanding of our planet’s development through time, from Creation Week, through the Flood, and onto the present day.

Footnotes

- Playford, P. E. (1980). “Environmental controls on the morphology of modern microbialites at Hamelin Pool, Western Australia.” Geological Survey of Western Australia. Annual Report for 1979: 73–77. ↩︎

- Reid, R. P, P. T. Visscher, A. W. Decho, J. F Stolz, B. M Bebout, C. Dupraz, I. G Macintyre et al. (2000). “The Role of Microbes in Accretion, Lamination and Early Lithification of Modern Marine Stromatolites.” Nature 406, no. 6799 (31 August): 989–992. ↩︎

- Gebelein, Conrad D. (1969). “Distribution, morphology, and accretion rate of recent subtidal algal stromatolites, Bermuda.” Journal of Sedimentary Research 39, no. 1: 49-69. ↩︎

- Berelson, W. M., F. A. Corsetti, C. Pepe-Ranney, D. E. Hammond, W. Beaumont, and J. R. Spear. (2011). “Hot Spring Siliceous Stromatolites From Yellowstone National Park: Assessing Growth Rate and Laminae Formation.” Geobiology 9, no. 5 (September): 411–424. ↩︎

- Eagan, K. E., and W. D. Liddell. (1997). “Stromatolite biostromes as bioevent horizons; an example from the Middle Cambrian Ute Formation of the eastern Great Basin.” In Paleontological Events: Stratigraphic, Ecological, and Evolutionary Implications. Edited by Carlton E. Brett, and Gordon C. Baird, 285–308. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. ↩︎

- Allwood, Abigail C., Malcolm R. Walter, Ian W. Burch, and Balz S. Kamber. (2007). “3.43 Billion-Year-Old Stromatolite Reef from the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia: Ecosystem-Scale Insights to Early Life on Earth.” Precambrian Research 158, nos. 3–4 (5 October): 198–227. ↩︎

- Peters, Shanan E., Jon M. Husson, and Julia Wilcots. (2017). “The Rise and Fall of Stromatolites in Shallow Marine Environments.” Geology 45, no. 6 (June): 487–490. ↩︎

- Wise, Kurt P., and Andrew A. Snelling. (2005). “A Note On the pre-Flood/Flood Boundary in the Grand Canyon.” Origins 58 (June 1): 7–29. ↩︎

- Peters et al., 2017, (Footnote 7). ↩︎

- Coulson, K. P. (2021). “Using Stromatolites to Rethink the Precambrian-Cambrian Pre-Flood/Flood Boundary.” Answers Research Journal, 14, 81–123. ↩︎

- Dickens, H. and Snelling, A.A. (2008). “Precambrian geology and the Bible: a harmony.” Journal of Creation 22(1):65–72. ↩︎

- Wise, Kurt. (2003) “The Hydrothermal Biome: A Pre-Flood Environment.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5, Article 32. ↩︎

- Hintze, Lehi F., Michael E. Taylor, and James F. Miller. 1988. “Upper Cambrian–Lower Ordovician Notch Peak Formation in Western Utah.” United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 1393: 1–29. ↩︎

- Coulson, Ken P., and Leonard R. Brand. 2016. “Lithistid Sponge-Microbial Reef-Building Communities Construct Laminated, Upper Cambrian (Furongian) ‘Stromatolites.’” Palaios 31, no. 7 (July): 358–370. ↩︎

- Coulson, 2021 (Footnote 10). ↩︎

- Whitmore, J.H. (2006). “The Green River Formation: a large post-Flood lake system.” Journal of Creation 20(1):55–63. ↩︎