How much time did it take to form the fossil-bearing rock layers of the geologic record? Short of having a Tardis or wormhole, we cannot go back into history and document the passage of time. Even supposedly foolproof methods like the various forms of radiometric dating employ a host of uncertainties, such as the unknown history of each rock sample. As such, geologists would benefit from having an independent method for measuring the passage of time without relying on these sorts of assumptions. A recent paper published in the journal New Creation Studies attempts to do so by studying intervals of bioturbation in sedimentary rocks.

The following article is a summary of “Bioturbation: Worm burrows and geological time,” by Leonard Brand & Art Chadwick, and of the surrounding discussion and research pertaining to it. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of New Creation.

What is Bioturbation?

Bioturbation is the reworking and mixing up of soil and sediment by living organisms. If you like to garden or farm, you are already familiar with the role worms play in this process. As they move through the soil, they mix it up, dispersing nutrients that plants can absorb.

But worms are not the only organisms capable of bioturbation. Plant roots, mice, gophers, squirrels, insects, worms, and even a certain now-extinct species of beaver mix up soil and sediment on land. On the seafloor, this is done by clams, bristle worms, and shrimp. Even large animals, like walruses, disturb the seafloor with their tusks as they search for food.

Obviously, the longer plants and animals have to bioturbate the soil or sediment, the more bioturbation they can do. This produces completely homogenized sediment or soil. All of the pre-existing layering is destroyed, the soil and sediment grains all jumbled up together.

Telling Time with Worm Burrows

If bioturbators are always working to mix up the sediment, why do we have a geologic record full of layers? This is what Drs. Brand and Chadwick wondered. Today, bioturbating organisms can readily homogenize layers of sediment over the course of hours, days, or weeks. It does not even take years.

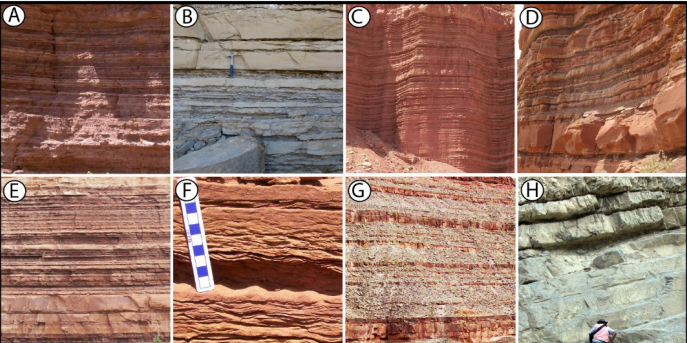

If the fossil-bearing part of the geologic record took 500+ million years to form, there should be far fewer stretches of it with fine, distinguishable layers. But if it formed quickly—over the course of perhaps less than 10,000 years—then visible, distinct bedding should be very common. The problem is that no one had actually tested this prediction. That is what Brand and Chadwick set out to do.

How was the Study Done?

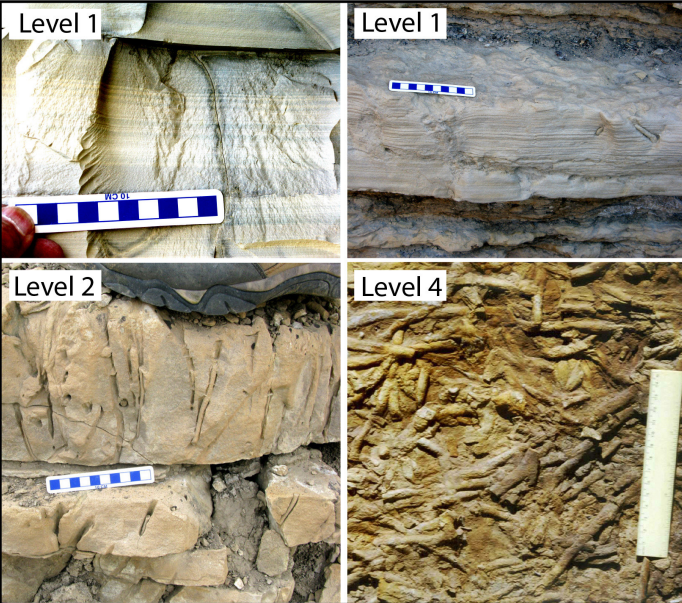

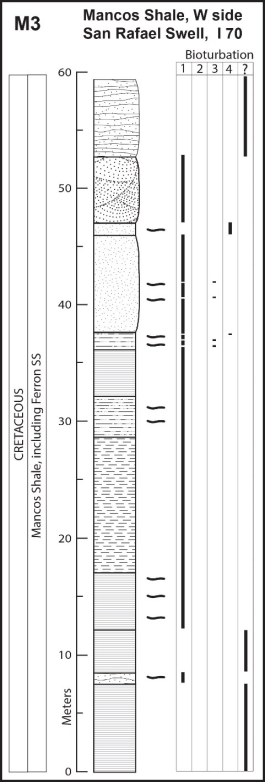

In order to test their hypothesis, Drs. Brand and Chadwick conducted an extensive survey. They examined 37 sedimentary formations from the Cambrian System to the Eocene Series in Utah, Arizona, and Colorado. They measured vertical sections of each formation and recorded the frequency and intensity of bioturbation present in each meter of sediment. The intensity of bioturbation is a widely recognized scale of 1-4. Level 1 includes the possibility of a small amount of burrowing, but not enough to significantly disturb the sediment layers. Level 4, on the other end of the scale, is bioturbation that fully obscures sediment layering.

the range of bioturbation density.

The formations examined included different types of sedimentary rocks, including sandstones (e.g., the Blackhawk Sandstone) and mudstones. This is significant because the general consensus requires long periods of low-energy conditions to form mudstone-dominated formations, like the Mancos Shale and non-marine alleged soils of the Morrison Formation. In other words, conditions would have been perfect for lots of bioturbation.

Findings

The researchers found that 97% of all the geologic sections they studied are Level 1, with either no bioturbation or occasional isolated burrows (Level 1). It was only the remaining 3% that contained Level 2 or 3 of burrowing intensity. They observed Level 4 rates in less than 1% of sedimentological records examined. This strongly confirms the prediction Brand and Chadwick made based on the hypothesis that sedimentary layers formed over thousands of years rather than hundreds of thousands or millions of years, like radiometric dating methods demand. This lack of bioturbation demands an explanation. Simply falling back on radiometric dating will not make this evidence disappear.

Future Research

Brand and Chadwick’s work here has provided a launching pad for additional research into bioturbation in the geologic record. There are other locations reported to have more bioturbation than in the strata they examined. Brand and Chadwick suggest that future research should set out to determine what factors differ between formations with high levels of bioturbation and those, like the ones they identified, with lower levels. Unfortunately, it is unlikely that rock formations with low levels of bioturbation and body fossils are going to be the subject of many published papers. This creates an unfortunate bias towards intervals with bioturbation in the literature.

Another area of interest for future investigation is the levels of bioturbation in the uppermost portions of the sedimentary record, called the Cenozoic. Many young-earth geologists regard these as having formed in the centuries to millennia following the Flood. Brand and Chadwick express that bioturbation research could yield valuable information regarding the transition from the large-scale and rapid geologic processes experienced during the Flood itself to the mostly slow-and-gradual conditions we experience today.

Conclusion

Given what we know about bioturbation as it occurs in the present, there is far too little of it present in the sedimentary rock record to be compatible with the passage of millions, or even hundreds of thousands of years. This observed lack of bioturbation makes much more sense if the sedimentary rock record formed over the course of just thousands of years. This simple study with a simple prediction powerfully shows that by starting from the events and timeline described in the Bible, young-earth scientists can conduct fruitful scientific research and come away with incredible findings.

I’ll try to read the primary paper, but is there any way to test if the diagenetic process is erasing evidence of bioturbation?

Read through the article and I guess I could say it presents a start, but there seems to be a lot more to be done. For example there is little discussion on the sedimentary formations via review of the literature – what is the present understanding of their depositional and tectonic history? This should be considered in the context of why there may be the presence of absence of bioturnation.

The paragraph on radiometric dating is curious. There is a comment that there is uncertainty in the history or the rocks, but it’s not clear if they refer to the sedimentary rocks they are reviewing or what. There is no mention or map of where the dating has been done in the region that sets the timeline for these features. Generally speaking, dating will be preferentially done on igneous rocks, not sedimentary – possibly on intrusive fragments within a conglomerate.

This is very interesting. The lack of bioturbation has always seemed like a strong argument for the flood and short history since then. Since I am very interested in post flood ecology, I would very much like to see research done on how bioturbation differs in different layers and what that may be able to tell us about the post flood ecosystems.

In 2012 we visited two quarries in Germany. For more than 8 years the photo’s remained a mystery. Then the jigsaw pieces came together.

God provided for a clock in the past and the present: the moon. Two times a day there is high tide and two times low tide. We couldn’t escape the conclusion that the fossilisation process must have been a continuous process. This discovery features our comprehensive paper against darwinism, modern geology and their spiritual poison.

Bert Kroeze (retired teacher of physics)

The Netherlands

https://exodushomechurch.com/a-unique-discovery-at-two-german-quarries/