In our quick journey through Mutology, the time has come to get our hands dirty. So far, we have defined the important terms and identified the challenge facing evolution’s ability to explain mutation rates. We know that observed mutation rate over time is orders of magnitude different from the estimated phylogenetic rates, which takes the number of mutations between two species and divides that number by the assumed amount of time separating those species from their common ancestor. We know that the observed mutation rate is much faster than evolution predicts or allows, since deleterious mutations would quickly build up in a species and cause extinction. Now, we must take a closer look at explanations offered by evolution for the mutation rate discrepancy.

The following article is Part 2 of a summary of “Genealogical vs Phylogenetic Mutation Rates: Answering a Challenge,” by Robert Carter, and of the surrounding discussion and research pertaining to it. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of New Creation.

The challenge evolution faces is explaining how thousands of mutations have been removed from populations over time. If a process could remove mutations from the gene pool of each species, then the discrepancy between the phylogenetic rate and the true mutation rate could be explained away. A removal of mutations means that these changes in the genome are not passed down to the next generation, therefore slowing the genealogical mutation rate.

Suggesting Selection

Recall that the problem for evolution here is a rock-and-a-hard-place scenario. On the one hand, evolution relies on mutations for new information to be added to each species’ genome. But since most mutations are harmful ones, too many mutations are harmful to a species. Fast mutation rates risk the extinction of the species while slow mutation rates are unsupported by current genealogical observations.

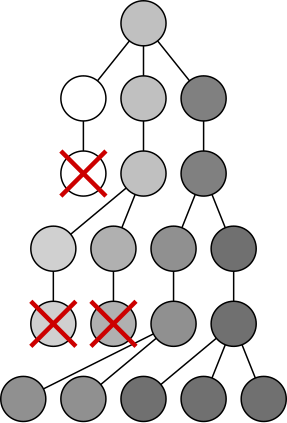

But one mechanism offers a possible solution for evolution, and it is none other than the Darwinian classic: natural selection. The idea goes like this: since natural selection removes organisms that are unfit for survival from a population, it also removes the mutations those organisms carry. Natural selection, in other words, discards “Unfit mutations.” This way, populations have a fast mutation rate in the short term, but a slow mutation rate if given enough time. Natural selection needs years to effectively remove bad mutations from the gene pool.

Digging Deeper

Now, here we must stop and acknowledge that it is important to not end the conversation here. It is fairly easy—even tempting—for creationists to argue that mutation rates refute evolution and leave it at that, just as it is easy for evolutionists to cite natural selection as a quick fix and move on. Doing so would leave creationists with a half-baked argument for a young earth, easily dismissable and ineffective.

But how can we test to see whether natural selection really does balance out the genealogical and phylogenetic mutation rates? Conventional evolution theory depends on natural selection modifying populations over the course of millions of years. Obviously, we cannot wait around and observe what happens to mutation rates over such vast timescales. This fact might be a source of comfort—both for evolutionists and creationists—as it allows us to confidently assert what would happen over long periods of time. Evolutionists assume natural selection would explain away their mutation rate problem while creationists confidently assert that natural selection can do no such thing.

The solution, of course, is modeling. Since we can estimate how frequently mutations occur, and the ratio between beneficial, neutral, and deleterious mutations, we can simulate what would happen to the mutation rate in a population over time. This is exactly what Robert Carter did with a simulation program called Mendel’s Accountant.

Modeling Mutations

Carter ran multiple simulations, some using human-like populations. For the first round of simulations, he accounted for the whole genome, while in others he analyzed only the mitochondrial DNA.

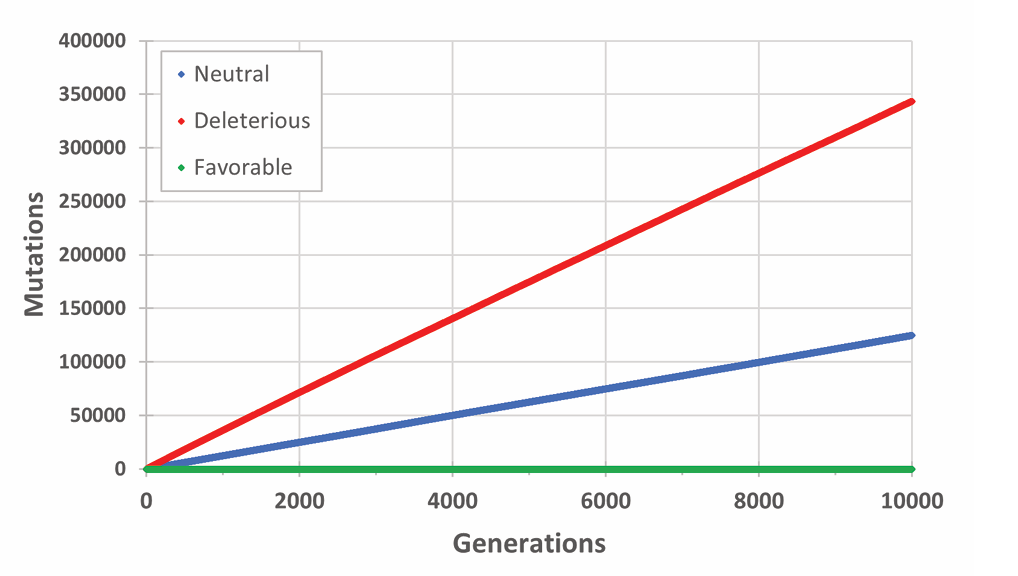

For the first type of simulation, Carter had to include several factors. Most obvious are rate of mutations and ratio of beneficial to deleterious mutations. But a less obvious factor that would impact the results is population size. Natural selection affects smaller populations more than larger ones. Carter accounts for this by running the same simulation with multiple population sizes (100, 500, 1,000, 5,000, and 10,000). He assigned a mutation rate of 50 mutations per person with a ratio of 1 beneficial mutation for every 1,000 deleterious mutations. These numbers are approximate but should yield realistic estimates. (to see all the factors he included, take a look at the original research paper).

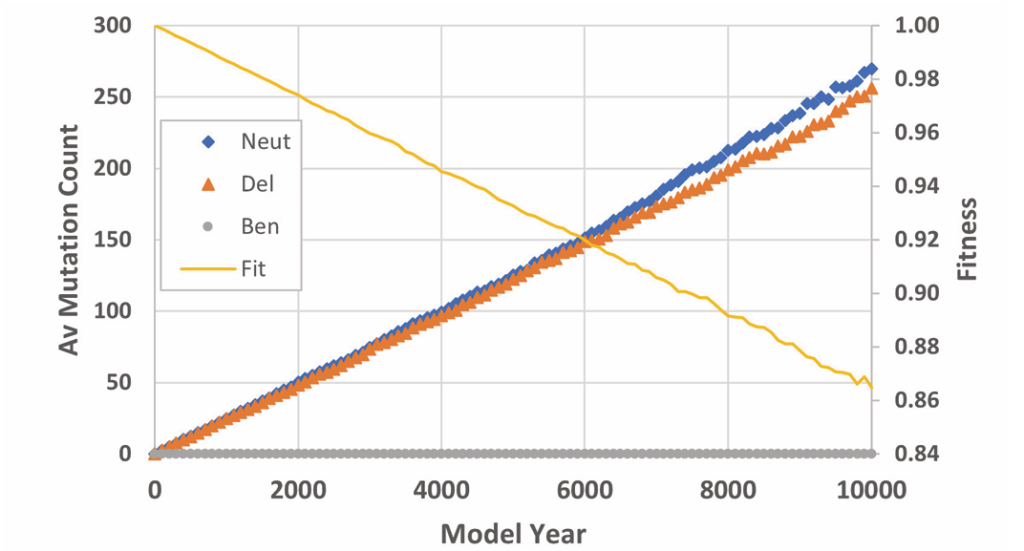

He then tested the mutation rates in mitochondria, a DNA carrying organelle in cells (recall that the DNA in your mitochondria is only inherited from the female parent, unlike the DNA in the nucleus). For this test, he used a section of DNA composed of over 16,500 nucleotides and tested a variety of mutation rates. He ran this simulation for 100,000 generations.

Reading Results

In the first type of simulation, all populations either went extinct or trended in that direction. If the simulation kept running for even longer, the populations likely would have died out. Significantly, neutral mutations built up in the population linearly, meaning that natural selection could not slow down the rate of mutations that had no effect on fitness. This makes sense, since natural selection only discards traits that are harmful to survival. In short, neutral and deleterious mutations accumulated at a predictably fast rate, regardless of natural selection or the presence of beneficial mutations. Not only that, but when natural selection did remove mutations, the population trended towards extinction (more on this later).

In the mitochondrial mutation simulations, the populations began genetically perfect and over time, neutral and deleterious mutations grew in number. Selection began to take effect as negative mutations stacked up. However, natural selection did not remove nearly enough mutations to account for the phylogenetic rate. There are different reasons for this, depending on the size of each population.

The problem for large populations was that no mutations were fixed. In other words, no mutations, positive or negative, became the only version of that gene in the population, even after 300,000 years of simulated evolutionary time. Mutations steadily built up in the population but could not be selected against to the degree required. The fixation rate was simply too low. Even in the small populations, where fixation is more common, selection removed only 10-60% of deleterious mutations. Unfortunately for evolution, this still leaves an orders-of-magnitude difference between predicted and actual mutation rates.

Constructing Conclusions

The results of Carter’s research are unsurprising but significant. Essentially, the data suggests that mutation rates occur too quickly for evolution to occur. Natural selection can remove some deleterious mutations from the gene pool, but doing so requires the removal of organisms as well. The more natural selection works, the closer the population comes to extinction. We return to a rock-and-hard-place situation, with the “rock” being the fast mutation rates we observe in genealogies and the “hard place” being natural selection, which cannot lower mutation rates without killing off the whole population! Not to mention, neutral mutations are unaffected by natural selection entirely, and quickly build up in populations regardless of how involved natural selection is. The rapid mutation rate among neutral mutations, unhindered and untouched by Darwinian mechanisms, further confirms the young history of humanity.

Remaining Reflections

It has been a fun though brief trip through mutology. I hope this little bite-sized series has informed you about the genetic changes at the foundation of living things. It is important to remember that we should not merely grab onto the apparent problems facing evolution. We should especially avoid simply using them as talking points to support our own conclusions. Rather, we should take a deeper look at the solutions evolutionists postulate and follow them to their logical conclusions. Only by doing efficient research and accurate calculations can we research a topic fully and find answers that do not just tear down a current scientific theory, but also reflect the truths written in Scripture.

The changes that pass on from generation to generation are not merely mistakes and typos in the language of life. They are also a record of the past; remnants from ancestors most of us cannot name from memory. Just as God displays his glory through the glorious genetic code, He also ensures that even the mutations which inevitably creep in—the bad ones and the good—will still direct us to His creative works.